Maybe his name does not ring a bell, but you surely know this artist’s work. Giuseppe Arcimboldo is known for his anthropomorphic representations of fruits, vegetables, plants, animals, and objects. Though belonging to the Mannerist movement, Arcimboldo was a one-of-a-kind painter, sometimes seen as a modern artist well-ahead of his time.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo: A Painter in the Service of the House of Habsburg

Giuseppe Arcimboldo was born in Milan in 1527, to a family of painters. Biagio Arcimboldo, his father, worked as a painter for the Fabbrica, the council in charge of building, funding, and managing Milan Cathedral. Giuseppe started working with him on the designs for the cathedral’s glasswork. There are only a few pieces of evidence for Giuseppe’s training and early career. It is also unclear how he came to work in the service of the Habsburgs, one of the greatest ruling families in Europe.

Far from the eccentricities of his most famous works, Giuseppe started as a Court painter at the service of Ferdinand I, King of Bohemia and future Holy Roman Emperor. In 1562, he joined the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, first in Vienna, then in Prague. From the mid-15th century, the influential House of Habsburg ruled the Holy Roman Empire, one of Europe’s most powerful ruling nations. At the time, it gathered a large union of territories spreading from the North of Europe to parts of the Italian Peninsula. Giuseppe Arcimboldo had the privilege to work at the service of the Emperor, developing his talent while painting family portraits.

The Four Seasons and the Four Elements: The First “Composite Heads”

A year after joining the Emperor’s court, Arcimboldo started two series of work that soon became his trademark: composite heads. Arcimboldo first started with a series of paintings depicting the four seasons. The seasonal cycle is represented as four anthropomorphic portraits using plants, fruits, and vegetables, each relating to their respective seasons. These kinds of portraits are often called composite heads. Spring is illustrated by a feminine figure made of flowers and plants, while the painter used seasonal fruits and vegetables for the summer and autumn man; winter is mainly composed of plants. Each portrait represents a time in a man’s life, from the youthful spring woman to the old winter man.

With the Four Seasons, Arcimboldo created a glorified portrait of the imperial family. The diversity of plant species symbolized the Empire’s vastness and the seasonal cycle the Habsburg’s longevity. Giuseppe offered the four portraits — painted between 1563 and 1573 — to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. The painter made several copies of the Four Seasons with slight variations. Today, some of these paintings are exhibited at several museums, including the Louvre in Paris, France.

The second series of paintings is also composed of four pieces, each portraying one of the four natural elements: Air, Fire, Earth, and Water. The Four Elements series, also a gift for Maximilian II, is linked to the Four Seasons, where each season has its corresponding element. The Milanese poet, Giovanni Battista Fonteo, a friend of Arcimboldo, wrote a poem in Latin explaining the meaning of his friend’s work: “Summer is hot and dry as Fire. Winter is cold and damp as Water. Air and Spring both are warm and damp, and Autumn and Earth are both cold and dry.”

For the Four Elements, Arcimboldo used animals and objects to create human faces. The painter used birds for Spring, terrestrial animals for Autumn, and aquatic species for Winter. Summer stands out from the others as it is depicted using matches, firearms, lighters, and flames. No animals appear in Summer.

Arcimboldo’s style somewhat resembles Leonardo da Vinci’s taste for caricature. Just like the great master of the High Renaissance, Arcimboldo thoroughly studied natural species, vegetal and animal, to achieve a remarkable likeness in his paintings. In fact, Arcimboldo knew some of Da Vinci’s caricatures and was probably inspired by his work. The painter also had access to living exotic animals exhibited in the Empire’s capital.

The “Wunderkammer”: A Milestone in Arcimboldo’s Creativity

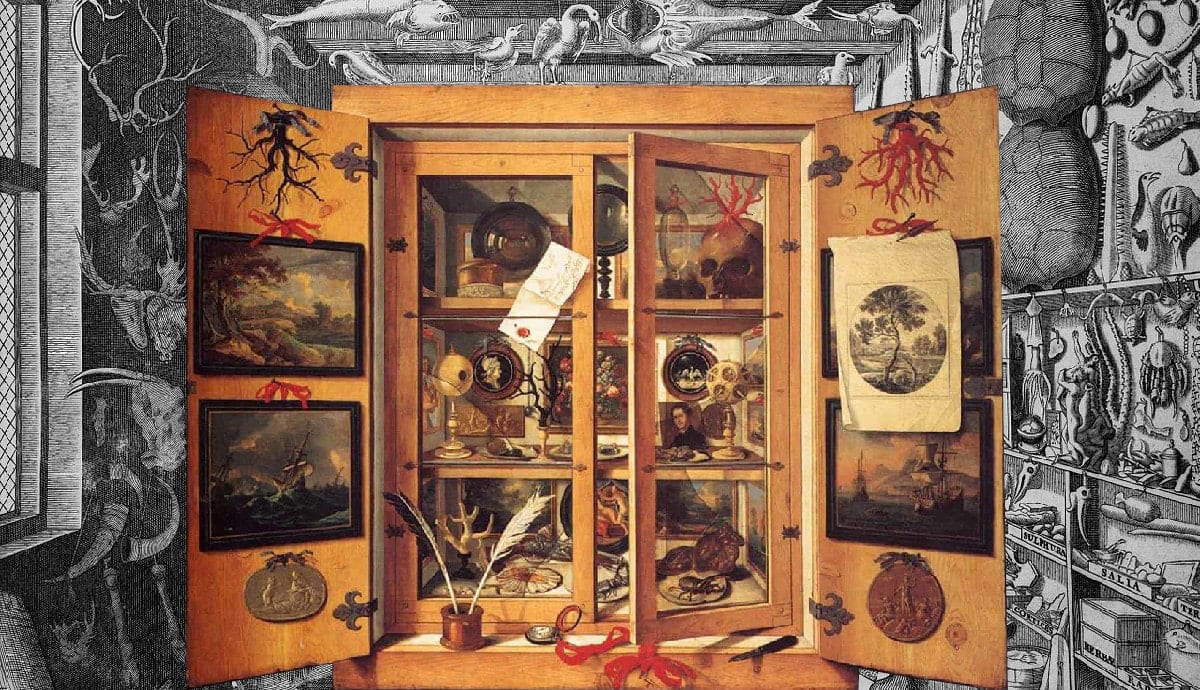

For twenty years, Arcimboldo worked between Vienna and Prague for the emperors Ferdinand I, Maximilian II, and Rudolf II. Besides painting portraits of the Emperor and his family, Arcimboldo also had a mission to enrich the notable “Wunderkammern” or “Kunstkammern.” The Wunderkammern, or cabinets of curiosities in English, were rooms dedicated to the collection and exhibition of rare or singular objects.

The trend for collecting scientific tools, minerals, plant and animal specimens, artifacts, and artworks, among other curious things, developed during the Renaissance. The rich and powerful showed their wealth by acquiring and exhibiting rare and precious objects. These collections were usually open to the public; some of them became the basis of future museum collections. The Habsburgs’ Wunderkammer was one of the finest European examples of a cabinet of curiosities. It certainly inspired the diversity of plants, animals, and objects depicted in Arcimboldo’s work.

On top of that, the painter also designed costumes, sets, and games used for the court’s entertainment. Some of his designs for costumes and chariots have survived. The Emperor also appointed him as the artistic and cultural counselor in charge of the enlargement of the imperial art collection.

Prolific Production of Composite Heads

For his prolific production of portraits, Giuseppe Arcimboldo used plants and animals but also other objects to represent human faces. In his portrait of a jurist, the artist used dead animals and fish to shape the head and sheets of paper and documents for the torso. Giuseppe delighted the Emperor’s court with this caricature of a jurist.

For the Librarian, Arcimboldo used objects to portray a man who may have been Wolfgang Lazius, the erudite man in charge of conserving the Emperor’s precious manuscripts. At first glance, we see a librarian with his arms full of books. Yet, the entire figure is made of books and related objects; a bookmark, duster, and a magnifying glass. The painting’s authenticity is questioned; it may be a copy of the lost original.

Arcimboldo’s originality did not stop at his composite heads, as he also created reversible portraits. Around 1590, Giuseppe painted the Fruit Basket. When presented the right way up, the spectator only sees an ordinary fruit basket, but it turns into a human face made of fruits when reversed. This technique, suggesting another perceived image, is called pareidolia and was also used by other artists such as Giotto and Leonardo da Vinci. Arcimboldo made several paintings using pareidolia. The Gardener, exhibited today at the Museo Civico Ala Ponzone in Cremona, not far from Milan, is hung the right way up. A mirror under the painting allows the visitor to see how the bowl of vegetables turns into a man’s face. An earlier painting of inanimate objects becoming a human face by pareidolia is The Cook, painted around 1570.

Another notable portrait painted by Arcimboldo is Vertumnus, a glorified representation of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Vertumnus was the Roman god of seasons, gardens, and fruit trees. The four seasons are all represented in the portrait using corresponding fruits and vegetables. Arcimboldo minutely chose each element’s position in the portrait; winter vegetables compose the torso, covered with a garland of spring flowers; autumn fruits and vegetables form the face. The head is crowned by a wreath made from the summer harvest.

Some of the fruits and vegetables represented, such as corn, were exotic at the time in Europe. The elements of this allegorical portrait stand for the Emperor’s power and prosperity and the other domains he ruled, such as the arts and sciences. Vertumnus became one of Arcimboldo’s most famous works.

The Mannerist Movement: Arcimboldo’s Symbolism

Today, Arcimbodlo’s work may appear curious or amusing, yet his true genius goes unnoticed. The forgotten symbolism of natural elements and objects deprives us of the key to unlocking the mysteries hidden in the painter’s work. In his paintings, Giuseppe carefully chose elements for their physical likeness to the anatomic parts he pictured, but he also leveraged their symbolism, giving several levels of meaning to his works. The paintings have to be viewed both from afar and close up in order to distinguish all their compositional elements.

Though Arcimboldo’s art is unique, it still falls within the great diversity of the Mannerist movement. This Late Renaissance art movement included an intellectualized form of expression and included artworks filled with codes and symbols, mostly understandable only to scholars and educated people.

Arcimboldo mixed two genres in his paintings: portrait and still life. The latter flourished during the late 16th century. Unlike Renaissance artists who placed the human figure at the center of the world to emphasize their domination, Mannerism depicted humanity as part of an ever-changing and volatile universe.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo: A Role Model for Modern Painters

During his lifetime, Arcimboldo knew great fame. In 1587, he left court to live his final days in his hometown Milan. A few years later, Rudolf II gave him the noble title of Earl Palatine. Giuseppe Arcimboldo died in Milan in 1593.

Though Arcimboldo was not the only painter creating grotesque portraits, he established a very distinctive style. The painter never taught students. Still, numerous artists of his time made copies of his work. The genre of composite heads remained in vogue during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

Sadly, Arcimboldo’s work was forgotten soon after his death. It was only rediscovered four centuries later and once again praised by artists and critics. During the 20th century, modern painters, especially from the Surrealist movement, rediscovered Arcimboldo’s composite heads and acknowledged his avant-garde style. A member of the Mannerist movement, Arcimboldo was also a one-of-a-kind painter, and perhaps a modern artist who was well ahead of his time.