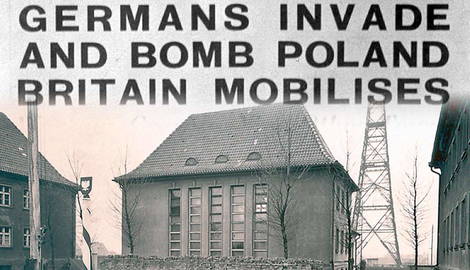

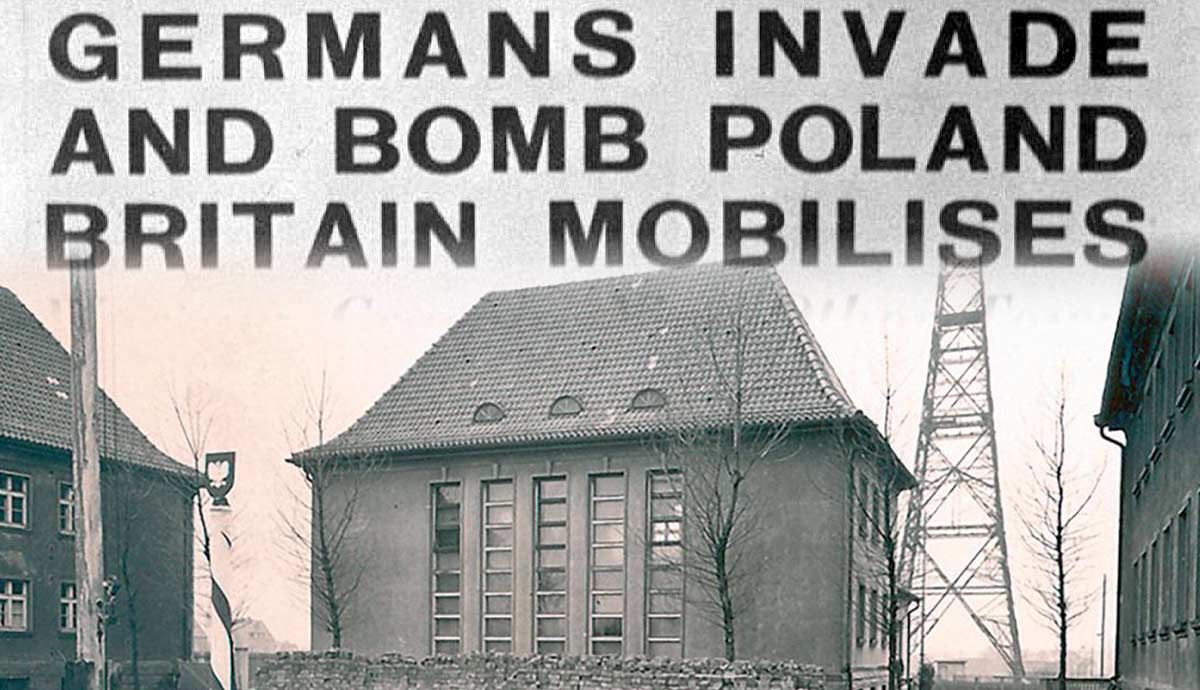

Nazi soldiers launched a simulated attack on the German-run Gleiwitz radio station on the evening of August 31, 1939. The action, which is widely referred to as the Gleiwitz Incident, was designed to give the impression that Poland was attacking Nazi Germany. Part of Operation Himmler, the incident to justify Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, can be seen as marking the start of World War II.

Background to the Gleiwitz Incident

The Third Reich was founded on inherently violent and race-based beliefs. Adolf Hitler believed that the World War I-ending Treaty of Versailles humiliated Germany and shrank its borders. Germany had lost its strategic territories, including upper Silesia and parts of West Prussia and Posen (today Poznań). Additionally, East Prussia was cut from the remaining Germany following the creation of the Polish Corridor, a strip of land that provided the Second Republic of Poland access to the Baltic Sea and divided the province of East Prussia from the majority of Weimar Germany.

Apart from the strategically important lands, Germany lost up to five million people, including those of German origin, who resided in these territories.

Hitler promoted the idea of Lebensraum, or living space in English. The term implied that Germans, as a master race, were in need of land and material resources; thus, the Third Reich should expand eastward in Europe, laying the basis for Nazi Germany’s expansionist foreign policy.

Adolf Hitler succeeded in implementing part of his plan to bring together the primarily German-populated regions of Nazi Germany by 1939. Without resorting to armed conflict, he had already absorbed Austria, Sudetenland (the western, southern, and northern parts of the former Czechoslovakia, inhabited mainly by Sudeten Germans), and eventually the entirety of Czechoslovakia before the start of World War II. Hitler’s expansionist ambitions required Poland to become part of the Third Reich. Hitler’s decision was clear regarding Poland’s occupation.

He outlined:

“Expanding our living space in the east and making our food supply secure, to have sufficient food, you must have sparsely settled areas. There is therefore no question of sparing Poland, and the decision is to attack Poland at the first opportunity. We cannot expect a repetition of Czechoslovakia. There will be fighting.”

However, the invasion of Poland was challenging. In March 1939, the Anglo-Polish Alliance was formed. According to the agreement, Poland would get military support from the British government in case of foreign aggression. The French government also supported the alliance. Furthermore, Adolf Hitler feared losing control of public support due to the traumatic experience of World War I, the chaotic years that followed, and the terrifying prospect of another war.

He came up with the idea to justify the invasion as Germany defending itself from the aggressor, in this case, from Poland. The strategic calculation was twofold: first, the idea of a foreign aggressor invading Germany would strongly resonate with the German population. Secondly, international support for Poland might loosen if it were portrayed as an aggressor state.

In a meeting with military representatives held on August 22, 1939, Hitler clearly expressed his approach:

“I shall give a propagandist reason for starting the war, no matter whether it is plausible or not. The victor will not be asked afterward whether he told the truth.”

Another carefully thought-out scheme prior to the invasion of Poland was the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Soviet Union on August 23, 1939. Adolf Hitler viewed the pact as an opportunity to do the following:

- annex Poland without opening the second front with the West;

- avoid the interference of the Soviet Union in the process of Poland’s annexation;

- and secure the Soviet guarantee not to aid Great Britain or France in case of war.

The secret protocol of the pact played a decisive role. It completely reshaped Eastern Europe by granting Bessarabia (a region today residing primarily in Moldova), Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and eastern Poland to the Soviet Union. Nazi Germany acquired control over West Poland.

American historian Timothy Snyder described the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact as follows:

“The two regimes immediately found common ground in their mutual aspiration to destroy Poland. Hitler saw Poland as the ‘unreal creation’ of the Treaty of Versailles and Molotov as its ‘ugly offspring.’”

The strategic plan to invade Poland was known as the Fall Weiss (or Case White in English), and propaganda was essential to the plan. Throughout the whole duration of August, Nazi-affiliated press and media outlets published numerous reports indicating the threat of “Polish terror,” “Polish bandits,” “growing nervousness,” and the “frightful suffering” of the German minority.

Adolf Hitler outlined his expectations and reservations about Polish occupation. Speaking to his military leaders on August 22, 1939, Hitler described his vision for Poland’s annexation, but he also envisaged the physical extermination of Poles and Jews living in Poland “with the greatest brutality and without mercy.” This vision became a reality, resulting in violence in the form of genocide: extermination camps, mass arrests, and murders.

The first step of the well-thought-out Polish invasion was to execute a series of staged attacks along the Polish-German border to portray it as originated as a Polish aggression. The attempts are widely referred to as Operation Himmler. The operation was named after Heinrich Himmler, the well-known high-level Nazi official who was the creator of the plan. Later, it was supervised by Heinrich Müller, the chief of the Gestapo, the secret state police of Nazi Germany, and then by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Security Main Office.

The false attacks came in the form of Nazi raids, including an attack on a German customs post where Nazi soldiers, shouting in broken Polish, imitated the border intrusion. Six prisoners, mainly Polish, were forcibly taken from the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. By this time, Adolf Hitler had successfully established concentration camps in Germany, the Dachau concentration camp being among the first ones. The Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, located in Brandenburg, opened in 1936. There, Nazi Germany placed their political prisoners, criminals, and socially or ethnically undesirable by the Nazi ideology. The Nazis dressed prisoners in Polish military uniforms, shot them, and left them at the scene. Technically, these inmates can be regarded as the first victims of World War II.

Adolf Hitler himself conceived the plan to stage an attack on the Gleiwitz radio station with the assistance of his chief of the general staff, General Franz Halder, and commander in chief of the campaign, Walter von Brauchitsch. The final result of the attack was meant to portray Polish military personnel having caused the hostilities between the Polish and Nazi forces.

The Gleiwitz Incident

Heinrich Müller, the head of the Gestapo, ordered Alfred Naujocks, a member of the Nazis’s Einsatzgruppen, or “mobile killing squads,” to implement the operation. The scenario of the staged assault was planned as follows:

Müller designated five of his officers and ordered them to disguise themselves in Polish military uniforms. He also informed Naujocks that this team would “receive several cans of meat” to be transported and placed at the radio station. What Müller meant by the “canned meat” was a Polish inmate from the concentration camp (reportedly Dachau), drugged and shot dead to make the Polish aggression more realistic. That man was Franciszek Honiok, an ethnic Pole but a German citizen living on a farm near Gleiwitz. Honiok was reported to be involved in anti-German agitation campaigns, making him a perfect candidate to be used for the staged attack.

Much later, at the Nuremberg Trials during 1945-1946, Alfred Naujocks shed more light on the plan’s details, contributing to the rising awareness of the Gleiwitz Incident. He also mentioned that he had been instructed to write a propaganda message that would be transmitted from the station. The message’s transmission is a nuance that makes the Gleiwitz Incident distinct from other staged attacks. It was the first (and, as it later appeared, the last) time that the officers were ordered to give voice to the operation and broadcast it to the rest of the world.

Alfred Naujocks planned the attack for 8 p.m. when residents were already at home with their radios on.

The plan was executed successfully, aside from a minor technical problem with the microphone. Just minutes after entering the radio station, a fluent Polish speaker from the designated SS (Schutzstaffel, or Protection Squads) officer’s group pulled a sheet of paper from his pocket and declared, “Attention! This is Gleiwitz! The radio station is in Polish hands!”

Nazi officers left the deceased body of Franciszek Honiok at the scene to be later used as evidence of a Polish attack. The Nazi propaganda machine was quick to portray the death of Franciszek Honiok as “killed in a brazen attack.”

A coded phrase that greenlighted the pseudo-attack was “Grossmutter gestorben” or “Grandmother died” in English. The next morning, the Nazi tanks and artillery were already heading to invade Poland. World War II began on September 1, 1939. Adolf Hitler declared in front of the Reichstag, German parliament: “Polish Army hooligans had finally exhausted our patience.”

Legacy of the Gleiwitz Incident

The information and details regarding the staged attack on the radio station in Germany were not public until the Nuremberg trials. Even after that, the history of Gleiwitz and its victim, Franciszek Honiok, has been overlooked for the most part.

The Gleiwitz Incident illustrates how history is shaped by political figures and media outlets, echoing Napoleon Bonaparte’s remark: “What then is, generally speaking, the truth of history? A fable agreed upon.”