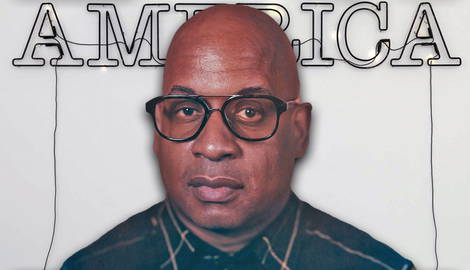

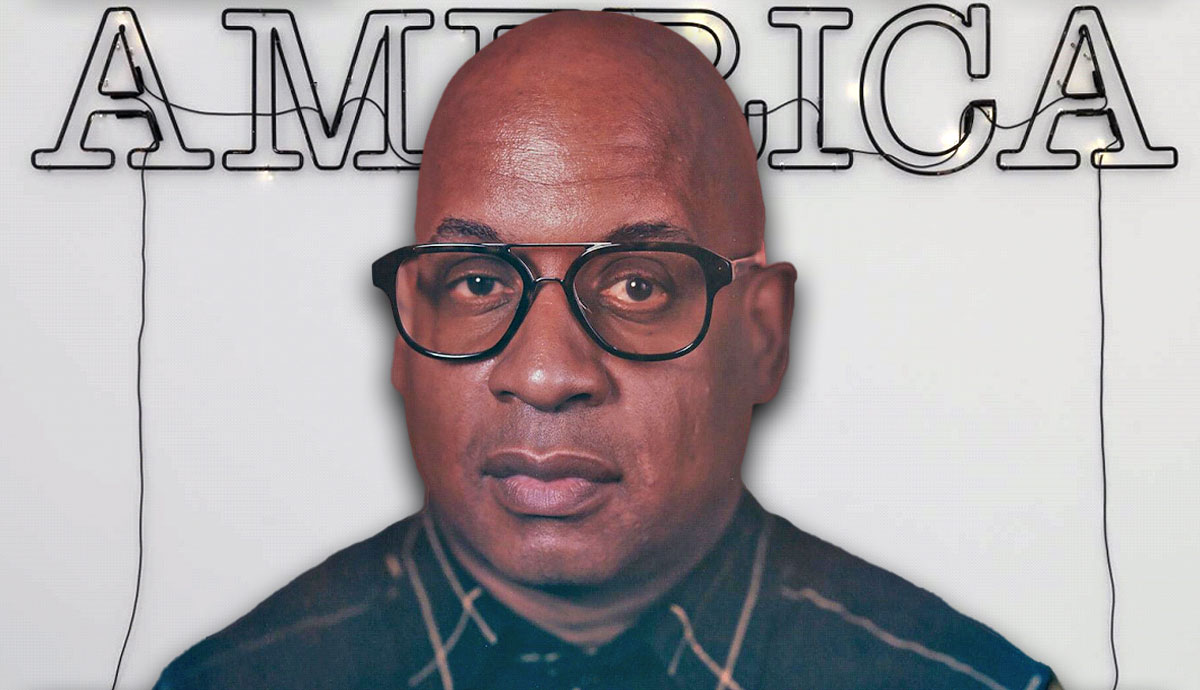

Glenn Ligon was born in New York City in 1960. He is considered a conceptual artist, as his work is idea-driven, expressed in a variety of formats from neons to paintings. Despite not being a writer, the New York Times claims that Ligon has inherited James Baldwin’s mantle to become the foremost philosopher on race and identity in America. Read on to learn more about Glenn Ligon.

Glenn Ligon’s Beginnings

Glenn Ligon comes from a humble, working-class background. He grew up in public housing in the Bronx. However, his parents had big ambitions for him, especially his mother who worked as a nurse’s aide in a psychiatric hospital and was separated from her husband. When Ligon was young his mother was called into school. She was told that her kids were finishing their assignments early and needed to be kept busy, so as not to disturb the other children. The principal of the school encouraged Ligon’s mother to look for better opportunities for her children.

A teacher then made a comment that while her kids were smart for that public school, they would just be average students in a good school. Angered by this comment and the low expectations, Ligon’s mother focused on finding a better school for her children. As a result, Ligon was granted scholarships to attend the Walden School which was a highly regarded progressive private school in Manhattan.

The artist often talks about his classmates at Walden. These were children coming from rich families whose parents owned important pieces of art. Lingon also mentions how he’d have to change his entire manner once he arrived back in his tough Bronx neighborhood so as not to appear different from others and get beaten up.

Ligon studied at the Rhode Island School of Design, ultimately graduating with a BA from Wesleyan University in 1982. His first early influences came from artists such as Philip Guston, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. He worked for years in a law firm without even mentioning that he was an artist. At some point, his own identity as a Black, gay man began to seep into his work. This was a turning point for him to find his unique voice in the art world. Interestingly, finding his voice often involved using the words of someone else.

He first broke on the scene in the 1990s after attending the Whitney Museums’ prestigious independent study program. This program often serves as a breeding ground for artists who meet a high bar of talent and intellectual rigor. Other artists who’ve come out of that program include Mark Dion, Julian Schnabel, Felix Gonzalez Torres, Yvonne Rainer, and Jenny Holzer.

Journey to Success in the Art World

One of the first works that established him as an artist worth watching, is the provocatively titled Untitled (I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background). The word colored refers to outdated historical usage to denote an African American. These and other early works tackled race, society, and cultural issues with seemingly abstract, textural paintings. The work was created using a white door that the artist found. In this piece, Ligon stenciled the same sentence repeatedly, almost like a mantra, until the letters cramped and dissolved into each other. They eventually become abstract figures.

The difficulty he had with creating crisp stencil lettering and the material itself, began to dictate what would evolve in the work. The natural blending and build-up of the oil paint led him to realize that that problem, rather than being a mistake, served the purpose of the work. The text used was taken from a quote by Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston from her 1928 essay How It Feels to Be Colored Me. In an age of intense segregation, Hurston explored the first encounters outside of the insular Black community of her childhood. She was suddenly confronted by the issue of race. Ligon’s painting’s cramped illegible texts convey her confusion and overwhelming feelings.

Another powerful early work that is rich in context is Untitled (I Am a Man). Initially, the work might seem bland unless you know its backstory. It’s a simple painting that relates to the signs carried by 1300 striking African American sanitation workers in the southern U.S. in 1968. The signs were made famous in Ernest Withers’ 1968 photographs of the historic protest. The strike was caused by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers that were using inadequate equipment in unsafe conditions.

The original slogan was a play on a line from Ralph Ellison’s prologue to Invisible Man that features the words I am an invisible man. By removing the word invisible, the Memphis strikers asserted their existence and dignity. Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis to address the workers and the following day, he was assassinated. One can see why Ligon was drawn to this simple yet powerful statement.

The Power of the Unreadable: Exploration of Text and Identity

Rather than an emotional approach to real-world issues, Ligon’s paintings have a cerebral and thoughtful quality. He subtly uses letters, typography, and dense text to convey meaning. His works are not always easy to read, literally and figuratively. The frustration they can elicit because of this might be part of their meaning. The titles are often the only way to begin understanding the work. There has to be a willingness to engage intellectually with his work.

A painting titled White #15 features primarily black oil paint on linen, but it’s a work that needs to be seen up close in person to get a sense of what critic Sebastian Smee meant when he wrote that despite the obtuseness of the work, he was drawn in by the oily matte-and-glossy textures, by the pattern made by the rows of black-on-black typeface, and by the work’s weird passive-aggressive intensity. It’s almost as if the work challenges you to understand it and to read into it.

The Breakthrough Biennial

The audience’s willingness to engage was tested by his entry to the 1993 Whitney Biennial titled Notes on the Margin of the Black Book. According to a 2021 New York Times article, the work was roundly disparaged by the predominantly white and male critical establishment… the critic Robert Hughes called it one big fiesta of whining. The work featured an installation in which the artist framed pages from Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1986 book of eroticized photographs of Black men. Lignon juxtaposed them with commentary from diverse sources, emphasizing the various fears and fantasies projected onto the Black men’s bodies.

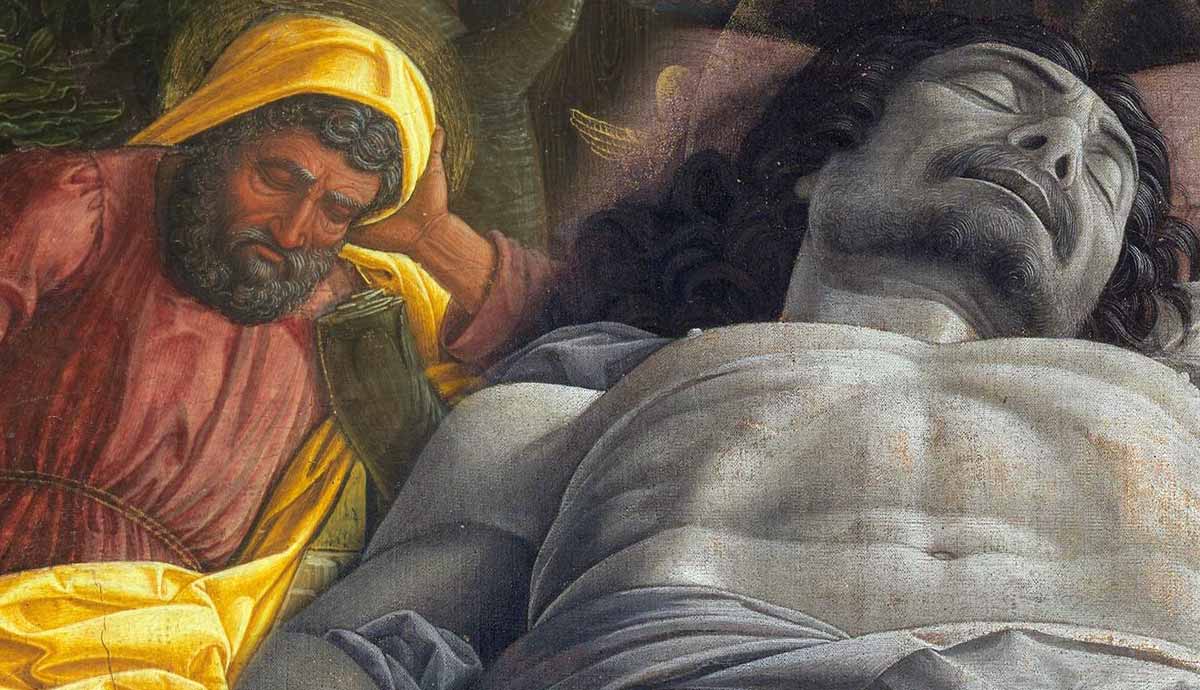

In that same installation, he returned to the works of James Baldwin once again. He referenced Baldwin’s Stranger in the Village with a quote that reads: It is one of the ironies of Black-white relations that, by means of what the white man imagines the Black man to be, the Black man is enabled to know who the white man is. Decades later his cerebral exercise for the Biennial resonates more deeply, because of the displays of violence enacted against Black men in public spaces, which has sparked public discussion and outrage.

Along with literary figures Ligon has engaged with popular culture, for example, the work of American comedian Richard Pryor, who was a profane, shocking performer during his time and had a tremendous influence on other comics. Ligon first heard the comedian when he was still in his teens. Pryor inspired a series of works titled No Room (Gold) that was first exhibited in Los Angeles in 2007. The series featured 36 gold canvases with Pryor’s trenchant quotes stenciled in black. The quote I was a nigger for twenty-three years – I gave that shit up – No room for advancement was taken directly from the comedian’s stand-up routine.

Goodbye Canvas, Hello Bright Lights

More recently, Glen Ligon has started working with neons. A work titled Some Black Parisians, which was exhibited at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, shows the names of Black models, performers, and writers who were featured in important French works of art from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some, such as the famous entertainer Josephine Baker are still remembered. But many who were portrayed in famous works, have slipped into obscurity.

For example, the woman who posed as the maid for Édouard Manet’s famous painting Olympia is a primary figure in the composition. Still, her surname is unknown and her presence is often barely acknowledged in art history. By lighting these names up, the artist added the glamor and prestige that comes with the neon material.

Glenn Ligon Today

Glenn Ligon currently resides in New York City. He continues to exhibit his works internationally. Ligon’s extensive body of work explores the concepts of identity, whether societal, racial, or individual. For this, he uses sources taken from literature, fine art photography, and pop culture. Ligon’s wide range of literary references goes from Zora Neal Hurston to Walt Whitman, from Gertrude Stein to James Baldwin. All of these sources serve as fodder for the artist’s exploration of the impacts of slavery, civil rights, power, and sexuality of Black men in America.