If God knows everything that will happen, and God cannot be wrong, then how can we have the free will to change the future? This article will explain why God’s all-knowing nature raises concerns for free will, some well-known attempts to show that these concerns are ill-founded, and some further questions that these attempts raise.

Before we begin, ask yourself one question—if God knows everything, did he know three years ago that you were going to read this right now?

Free Will and Divine Foreknowledge: What’s the Problem?

Many religions view God as all-knowing, or omniscient. This makes sense for these faiths—some of the holy books within these religions are prophetic in nature, explaining not only the events that occurred when they were written, but detailing events that will happen in the future as well. This could not be possible if God did not know everything, including the future.

Moreover, God cannot be wrong according to the tenants of these religions. This can be a comforting thought since it would mean that those who adhere to these religious beliefs know that they are choosing the right side.

However, the implications of an all-knowing divine being can actually be a bit discomforting. If God knows everything, that means that they have known exactly what you will do at every second of your life since before your great, great, great, great, great, grandparents were born. God knew that you were going to skip class in 9th grade, that you were going to read this article today, and what you will have for dinner next week.

However, if God knows what you are going to eat for dinner in 3 days, and God’s knowledge cannot be wrong, then logically, you cannot eat anything else—to do so would be to contradict God’s knowledge. As such, how can you be said to have the free will to choose what to have for dinner, or to do anything for that matter?

God, Free Will, and Punishment

The problem of divine foreknowledge and free will is closely related to the problem of evil, which asks why a God who is all-powerful, all-knowing, and supremely good would allow evil to exist.

Like the problem of evil, the problem of divine foreknowledge and free will is specific to those religions that believe in an omniscient deity, i.e., an all-knowing god. This would preclude religions like those discussed in the Viking sagas or practiced by the Greeks and Romans.

God’s omniscience is well-established in many of the Abrahamic religions, which include Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, among others. In the book of Psalms, a holy book in both Judaism and Christianity, God is described as “abundant in strength; His understanding is infinite” (Psalms 147:5). The Quran (Koran) states that “Allah is Knowing of all things” (Holy Qur’an 49:16).

Because of this, the problem of divine foreknowledge and free will has preoccupied Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scholars for well over 1,500 years. This makes sense since the majority of sects within these religions believe in an afterlife that is determined based on our choices in this one. If we have no choice in what actions we take, then it seems problematic to be punished or rewarded for those actions.

A tempting response to this issue that comes to many people’s minds immediately is that God knows all the paths that we might take, but the decision to choose which path to go down is still our own. However, this runs into the immediate problem that it still limits God’s knowledge, thus no longer making them all-knowing. If God only knows the possible paths we might take and not which one we will take, then God does not know everything and is no longer omniscient. Even if there are an infinite number of paths we can take, an all-knowing God will know exactly which one we will go down, and the issue still remains.

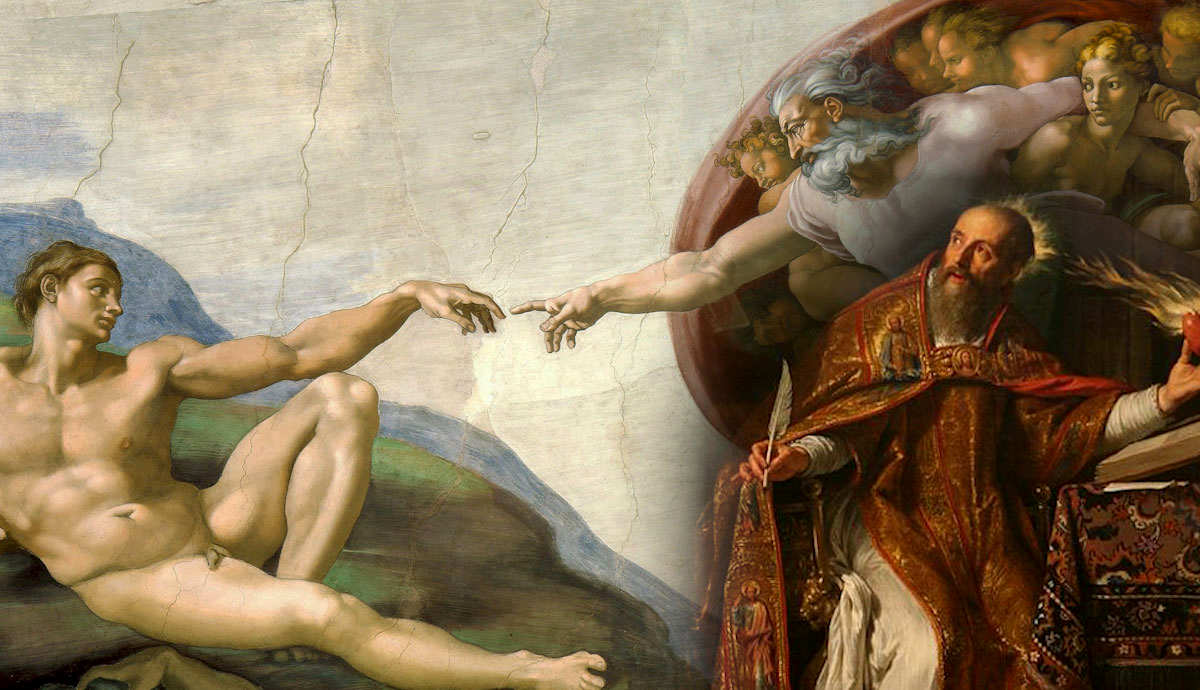

St. Augustine’s Response: Knowing versus Causing

One attempt to rectify the logical contradiction between divine foreknowledge and free will comes from St. Augustine of Hippo (354—430 C.E.), a well-known figure in both Western Philosophy and Christian theology.

Augustine argues in On the Free Choice of the Will that the reason there seems to be a contradiction between divine foreknowledge and human free will is that we confuse God’s knowledge of what we are going to do with God causing us to do something. He claims that we can know that someone is going to do something, but this does not mean that we are the cause of them doing so.

For example, suppose that you have a dog that barks every time the doorbell rings. One day, as you peek outside, you happen to see a door-to-door salesperson walk up to the door. Before you can get to the front door and stop them, they ring the doorbell, which you knew would send your dog into a barking fit. However, even though you knew your dog would bark, no one would say that you caused the dog to bark. Augustine presents a similar argument regarding God and foreknowledge—God knows that we will make a choice to either sin or not sin, but we are still the cause of that sin.

Boethius’ Attempt: For God, Everything is Present

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (circa 480—524 C.E.) presents an alternative response to the problem of divine foreknowledge and free will in his book On The Consolation of Philosophy, although it shares similarities with Augustine’s views on time, which he discusses in The Confessions of St. Augustine.

For Augustine, time does not exist in an objective sense; instead, humans construct the concepts of past and future in their minds, but only the present is real. Boethius draws on this idea to develop his solution to the problem – God, operating outside of time, views reality in a different way. For God, everything happens simultaneously.

This idea is difficult to comprehend for humans (in fact, impossible by their very nature), but an analogy that might help is to think of reality as a map on a table. Each occurrence in our lives, and in the universe as a whole, is an individual point on the map. At each moment in our lives, we only have the perspective of the point we are at, having passed the previous point and not yet experiencing the next point. However, God can see all parts of the map at the same time. We might not know what the next point looks like, but God does because they see them all at once.

In this case, there is no sense of God causing us to perform an act in the future because the idea of a future is not applicable for God. While this view of time may seem like a strange notion, it has garnered support from modern-day scientists, some of whom argue that the passage of time is just an illusion, as is explained in the article “Time’s Passage is Probably an Illusion” by Paul Davies.

Martin Luther: Why Not Accept Our Fate?

Some theologians have chosen to embrace the idea that God’s foreknowledge limits our free will. Martin Luther (1483—1546), famous for starting the Protestant Reformation in Christianity, explicitly states in On the Bondage of the Will that “since God’s foreknowledge is not uncertain, ‘free-will’ is non-existent” (1525).

For Luther, humans are predestined to be rewarded or punished after death. Of course, the immediate response to this is to ask why God chooses some people to be saved and not others, but Luther states that this is beyond our ability to understand. This is a secret that God has kept and “forbidden us to know” (Luther, 1525). This is akin to the idea that God has a plan, and we must simply trust in that plan, regardless of how it impacts our limited human perspective.

Alvin Plantinga: Actions Cause Knowledge

Other theologians, however, disagree with Luther and continue to argue that we can have free will even if an all-knowing God exists. One of the more famous modern defenses of free will comes from American philosopher Alvin Plantinga (1932—present).

Plantinga presents a response to the problem of divine foreknowledge and free will similar to Augustine’s, but with a focus on the linguistic aspects of the issue. In the traditional phrasing, the problem is presented as follows: God’s knowledge of the future causes us to commit certain acts. However, Plantinga’s response is that this formulation is backwards. Rather than God’s knowledge causing us to act, our actions cause God to know. Had we done something different, God’s knowledge would have been different. The causal relationship here is not from God’s knowledge to our actions, but instead from our actions to God’s knowledge.

Final Thoughts on Divine Foreknowledge and Free Will

The question of how to rectify God’s divine foreknowledge with human free will has concerned Western philosophers for well over 1,500 years, and with good reason. Most of us want to believe that we have the power to choose our own paths, and this issue raises serious questions about our ability to do so.

Philosophers have presented several arguments for why the existence of an all-knowing God doesn’t necessarily rule out our own free will. However, even if we are convinced by the likes of Augustine, Boethius, or Plantinga, there is still one thing that we could never have had control over in the first place—the creation of the universe itself.

If God knew when creating the universe that I would make a series of choices that would lead to my eternal suffering (assuming a theological belief in hell, which is not shared amongst all Abrahamic religions), it seems that it would have been more beneficial for me that God created nothing at all. Perhaps it is the case that God felt my suffering was worth it, or perhaps Luther is right that we simply cannot know the answers to these questions.