Graham Sutherland`s painting career only started around 1930. He made a choice to embrace his painting talent after visiting Pembrokeshire in 1935. The isolated landscapes in Pembrokeshire became Sutherland`s source of inspiration. Alongside John Piper and Henry Moore, Sutherland became one of the leading war artists in Britain. He became a renowned Neo-Romantic artist, and later on in his career (after World War II), he became Francis Bacon`s mentor. As an artist who later converted to Catholicism, Sutherland eventually made the move toward religious-themed works of art.

This article’s main source is Daniel Frampton’s article “Objectifying the Unknown: The Catholic Art of Graham Sutherland” published in Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture.

Who Was Graham Sutherland?

Graham Sutherland is one of the most overlooked British artists of the 20th century. Compared to the work of his counterparts, Sutherland`s artwork in recent years has received minimal exposure. As a landscape artist, he produced paintings that were numinous ecstasies. The possible impact of Catholicism on his works of art remains unstudied. Despite the labelling of his work as neo-Romantic, some of Sutherland’s art has a “religious” undertone even though it is not always obviously Catholic or Christian. Sutherland found a way to reconcile Catholic theological teachings with modernism.

During the early to mid-1920s, Sutherland studied etching and engraving at Goldsmiths School of Art under the guidance of Frederick Landseer Griggs (1876–1938), who was an English Catholic convert and draughtsman. As time went by, something about Sutherland changed; his new artworks became different from his earlier ones; they were different in terms of size (they were bigger), they used simple colors, and had new themes.

Lady Flavia de Grey (Flavia Irwin), a long-term Chelsea student, painter and wife to Roger de Grey, past president of the Royal Academy, said the following about Graham Sutherland:

“He was a terribly nice person, so sensitive so gifted … Such was his dependence on technique that students wrapped everything up very gently – get colours right. He says he did everything from observation. He had hardly done any teaching when I came along. He was a very atmospheric painter. He wanted you to find your own way. He bore [tolerated] the atrocious colours I used. He hardly talked about his own work. Just two or three hours with this man, it would set you up for the world. He was very much on the ball – he knew his materials. He used gouache almost exclusively. He let the students use the colours they wanted.” (Edited from talk by Flavia de Grey with Sara Morgan, Tate Library, 2005)

The Catholic Context

Sutherland converted to Catholicism a year before he married his Catholic wife Kathleen (nee Barry) Sutherland. Following their marriage, Sutherland confessed to art critic Robert Melville that converting to Catholicism came naturally to him. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Sutherland developed his own vocabulary for paraphrasing and objectifying the essence of his Catholic faith which became the main aspect of his artwork.

Sutherland said that through attending Mass he witnessed mysteries that delighted him; in his exact words, he said, “The Church objectifies the mysterious and the unknown. It gave my aspirations towards certain ends a more clearly defined direction than I could ever have found alone. It gave me a conception of a system whereby all things created, human and otherwise, down to the smallest atom — and its constituents — are integrated. It widened and superseded my vague pantheism. It also gave me a sense of tradition and of being a member of society. Even now, I cannot go into a church on the Continent without feeling a curious thrill at being present at the enactment of mysteries, which are enacted in precisely the same way in practically every country in the world, often at the same time. The sense of the canalisation of thoughts and energies on so vast a scale dumbfounds me. As to the effect on my work — who can say?”

Even though specific places were a source of inspiration for Sutherland, his intention was never to produce a painting that represented a specific time or place. Quintessentially, nature and the origins of active matter inspired him; however, he became concerned about how his separate discoveries and manner of interpreting specific organic creations could be modified and made suitable to European art lovers. He basically built his career around the European market.

Towards the end of the 1930s, Sutherland drew inspiration from Picasso when he produced the Neo-Romanticism styled artwork, Gorse on a Sea Wall (1939), which Anthony Blunt, British art historian deemed as the twentieth century`s main religious artwork. However, to understand what Sutherland was trying to objectify on paper and canvas, it is best to start by studying his forthrightly religious artworks such as the Crucifixion, Thorn Tree, and Thorn Head.

Graham Sutherland`s “Thorn Period”: Crucifixion

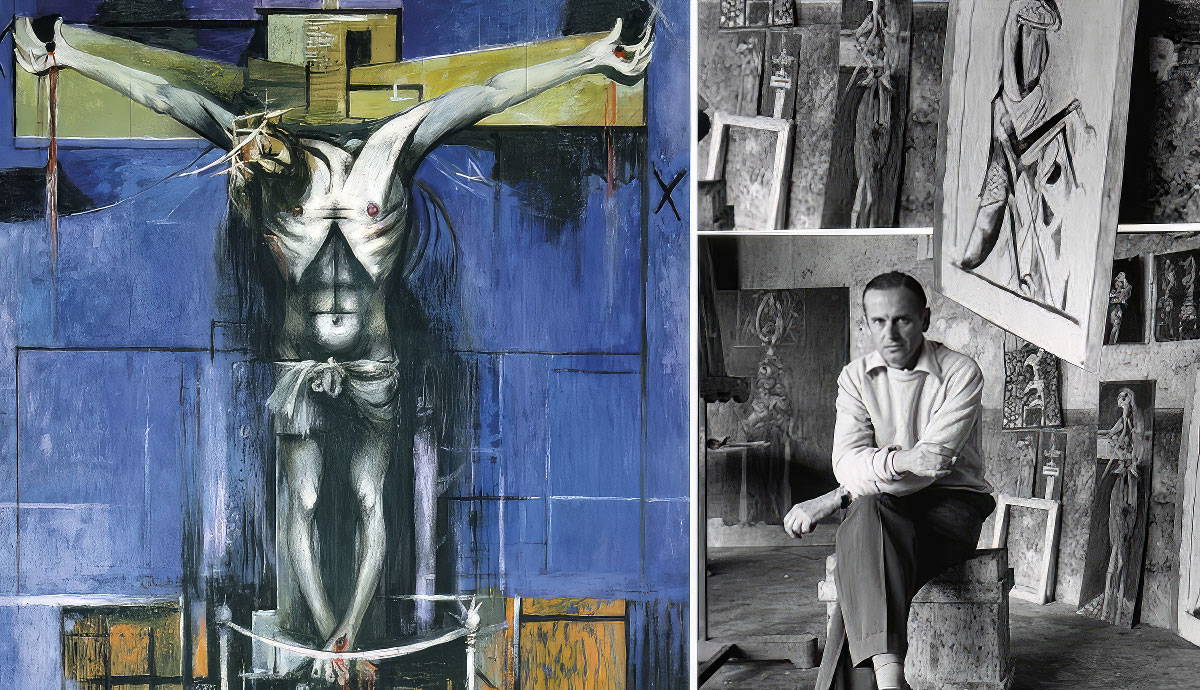

According to Roger Berthoud’s memoir on Sutherland, a priest at St. Aidan’s in East Acton believed that he saw Sutherland praying for guidance while painting the Crucifixion. Through the painting (the Crucifixion), Sutherland wanted to highlight the dreadful veracity of death. He did not want to gravitate towards the physical meaning; rather he wanted to show his generation the meaning of Jesus`s crucifixion.

When a person looks closely at Crucifixion he or she can see the hands that look like claws, the raised ribcage, and the disfigured shins; Sutherland did this to make the figure look austere and unrealistic. There is an inherent nobility about Christ’s death, which Sutherland exploited in order to show people what sin did to humanity, how it continues to disfigure the image of God in people, and how God plans to redeem the world.

The brick wall at the bottom of the cross emphasizes how civilized the society in which Christ`s crucifixion took place was; it cannot be said that society`s lack of civilization led them to crucify Christ — they knew what they were doing. The colors and design of the painting depict the sacredness and grace of Christ`s crucifixion. The background color shifts the mind away from the heart-breaking image of Christ’s disfigured body. The blue color inspires hope but it also inspires people to keep the faith that the day will dawn when darkness will cease to exist.

The most important aspect of the St. Aidan`s crucifixion painting regards Sutherland’s method of objectifying the unknown is Jesus’s thorn crown. As a type of a neo-Thomist, Sutherland was at his utmost best when he gave attention to something in particular — he came to realize that focusing on a particular object would give his work deeper meaning and would make the subject stand out. His focus on a particular subject is evident from his observation of thorn crowns and thorns in general. Art lovers saw him shifting from the mid-1940s landscape paintings to still lifes.

Sutherland once explained that, the Crucifixion fascinated him because of its symbolism, which stands out well in his oil on canvas Thorn Head, which is possibly his greatest achievement. The inside coloring in between the thorns imitates the blood in Crucifixion, and the bright colored background offsets the bloodthirstiness of the thorns and its extra spikes.

Thorn Head & Thorn Trees

Thorn Head (1945) was the beginning of Sutherland’s adoption of Picasso`s language. This artistic language intentionally interconnects with Catholic interpretation by focusing on a particular subject. The focus on thorns was already obvious in Sutherland`s Gorse on a Sea Wall from 1939 — the way in which the thorns on the gorse were personified led to the perfect personification of the thorns of Christ`s crown in Thorn Head.

In the ink and pen painting Thorn Trees (1945), the trunk of the tree impersonates the crucifix, a feature absent from Gorse on a Sea Wall. Sutherland used these artworks of thorns to exhibit a post-1945 mood of despair and anxiety but he also used them to show people how sin has pierced humanity.

Final Words on Graham Sutherland

Even though in recent times Sutherland`s work has evidently been neglected and marginalized, people can learn many things from his artwork. Undeniably, during the growth of his artistic career in the 1930s and 1940s he found his spiritual eyesight, which helped him to observe the unknown and actualize his artwork. Graham Sutherland’s Catholic faith definitely played a critical role in the valuation of his artwork.