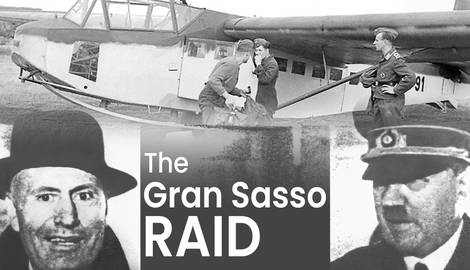

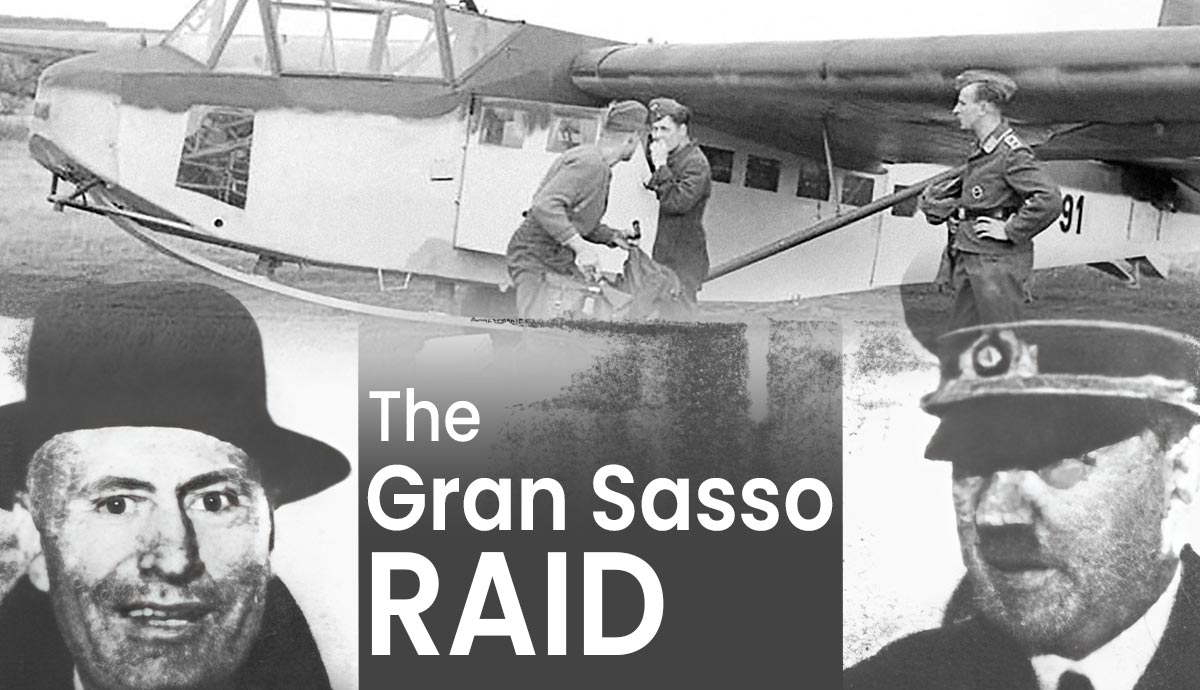

On September 12, 1943, a commando of German Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) landed on Campo Imperatore, a plateau above the Gran Sasso massif in central Italy. Their task was to rescue the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who was confined to this remote location as the Badoglio government negotiated an armistice with the Allies. In July, a group of high-ranking Fascist officials had voted to overthrow the Duce, who was then arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III. Alarmed by the unexpected turn of events, Adolf Hitler instructed the elite corps of paratroopers to organize a rescue operation. The Gran Sasso Raid became one of the most famous military enterprises of World War II.

The Fall of the Fascist Regime and the Gran Sasso Raid

In the summer of 1943, the Italian Fascist regime was facing defeat. Since joining the hostilities alongside the Axis powers, the Italian army suffered a series of military setbacks. In 1940, the Italian troops had to rely on German support to complete their attack against Greece. In May 1943, after the disastrous outcome of the second battle of El-Alamein, the regime’s North African forces capitulated. At the beginning of the same year, the Red Army annihilated the Armata Italiana in Russia (Italian Army in Russia), or ARMIR, sent by the Duce to assist the German army in Operation Barbarossa. Surrounded by the Russian soldiers, the poorly equipped Alpini (mountain infantry) began a tortuous winter retreat in the steppe that caused thousands of deaths.

To make matters worse, the increasingly frequent Allied bombing of the factories in the North slowed war production. To escape air raids and food shortages, countless Italians abandoned the cities. The widespread low morale eroded the popular support for the Fascist regime. At the same time, many anti-Fascist leaders began to re-enter Italy, where they actively encouraged and organized initiatives against the government. United by a common political goal, the various clandestine parties soon agreed to join forces to overthrow Benito Mussolini.

On June 10, 1943, the Allies invaded the Italian peninsula. After landing successfully on the coasts of Sicily, the Allied forces conquered the entire island in 39 days of fighting. The military defeats had led numerous high-ranking Fascist officials and representatives of the ruling class to question their personal and political loyalty to the Duce. The successful invasion of Sicily convinced them to remove the once-infallible leader from power.

On July 24, Dino Grandi, the President of the Chamber of Fasces and Corporations, called an extraordinary session of the Fascist Grand Council, which Mussolini created to replace the Italian Parliament, to address the situation. In the early hours of July 25, Grandi announced a new item in the order of the day: a vote of no confidence against Benito Mussolini. Nineteen members of the Grand Council voted for the motion, including Count Galeazzo Ciano, the dictator’s son-in-law. Only seven gerarchi (higher officers of the Fascist National Party) expressed their support for the Duce.

“The Most Hated Man in Italy”

Though the outcome of the Grand Council meeting shocked Benito Mussolini, he was confident that a government reshuffle would allow him to remain in power. On the afternoon of July 25, the Duce arrived at Villa Savoia, the royal residence on the outskirts of Rome, to meet with Victor Emmanuel III.

While Mussolini notified the king about the vote of no confidence, contesting its legality, the Italian monarch informed him that he could no longer support his leadership. “Surely you have no illusions as to how Italians feel about you at this moment. You are the most hated man in Italy,” supposedly declared Victor Emmanuel III. The king then announced that Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the former commander of the Italian forces during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, would replace him as head of government. He finally reassured Mussolini that he would personally guarantee his family’s safety.

However, as a shocked Mussolini left the building at around 5:20 p.m., a group of Carabinieri (the Italian military police) arrested him on the king’s order, hauled him into the back of an ambulance waiting near the royal palace, and drew him away. The day following the arrest, Marshal Badoglio officially announced that Victor Emmanuel III had entrusted him with forming a new cabinet.

As the news of the fall of the Fascist regime spread throughout the peninsula, jubilant crowds gathered in the streets to celebrate the end of Mussolini’s dictatorship. Overnight, countless Italians burned Fascist flags and portraits of the Duce, toppled statues, and discarded their black shirts and uniforms. After the war, the supposed inability of Allied officers to encounter any “real” fascist in Italy became a recurrent theme in the popular memory of the Fascist regime, suggesting that the “good Italians” had never fully adhered to Mussolini’s violent rhetoric.

In the days following the end of the regime, a growing confusion replaced the immediate euphoria. In his announcement, Badoglio declared that Italy would continue its military support for Germany. At the time, however, the newly formed government had already secretly contacted the Allied forces occupying the peninsula to inquire about a possible negotiated peace. Meanwhile, amid general uncertainty about the future, the Italian troops stationed alongside their German allies awaited orders.

Operation Oak

During the secret negotiations between the Allies and the Badoglio government, Benito Mussolini was an “awkward” prisoner for Italy. On the one hand, the government used the former Duce as a bargaining chip to obtain better peace terms and secure military support against Germany. At the same time, keeping Mussolini in Italy was not feasible. When Hans Georg von Mackenses, the German Ambassador in Rome, inquired after the whereabouts of Mussolini, Marshal Badoglio denied knowing the exact location of his confinement. However, the Italian government suspected that Nazi officials would eventually attempt to liberate their ally.

Italy’s apprehension was not without cause, as Adolf Hitler, upon hearing the events of July 25, immediately resolved to stage an exemplary action to retaliate the overthrow of the Fascist regime. After considering different options, including arresting the royal family and the officials who supported the plot against the Duce and destroying the Italian fleet, the Führer eventually opted for a rescue operation (nicknamed Operation Oak) to retrieve Mussolini from his prison.

The fall of the Italian dictator worried Adolf Hitler, who feared that the coup against the Fascist government might negatively affect the internal stability of the Reich. In early 1943, similarly to Italy, Nazi Germany was also undergoing a period of military setbacks. At the end of January, the Russian troops defeated the Sixth Army at Stalingrad, with Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus surrendering to the Soviets. By May, Erwin Rommel’s divisions lost the battle of El-Alamein in North Africa. In this difficult situation, the loss of the support of Fascist Italy on the Southern European front would lead to a strategic disadvantage. In particular, Adolf Hitler was afraid that the lack of Italy’s military backing would allow the Allied troops to advance through the peninsula.

Hitler sought to reinstate the Fascist regime to prevent the Allies from quickly reaching the border between Italy and the German Reich. To this end, from the Wolfsschanze (wolf’s lair), his headquarters in the woods of East Prussia, the Führer entrusted General Kurt Student, the commander of an elite group of paratroopers, with the task of rescuing Benito Mussolini. General Kurt gave Otto Skorzeny, an Austrian Hauptsturmführer of the Waffen-SS, the order to find where the Italian government hid the Duce.

After his arrest, Mussolini was shortly held at the headquarters of the Carabinieri in Trastevere, a neighborhood in Rome. On July 27, he was then moved to Gaeta, a coastal town south of the capital. The following day, Mussolini arrived at the island of Ponza. During the regime, the location was used for the confino politico (internal exile), the practice of exiling opponents of Fascism to remote villages and islands. Ironically, on July 28, among the small crowd gathered at the port to witness the arrival of the Duce was Pietro Nenni, a prominent member of the Italian Socialist Party confined to the island earlier in 1943.

At the beginning of August, the Badoglio government moved his prisoner to La Maddalena. Toward the end of the month, Otto Skorzeny finally managed to discover that the Fascist dictator was held as a prisoner on the small island off the shores of northern Sardinia. After a reconnaissance mission, Skorzeny and the paratroopers devised a rescue plan. However, the Italian authorities ordered a sudden relocation of Mussolini. On August 28, he was flown to Hotel Campo Imperatore on the Gran Sasso d’Italia in the Abruzzi region.

“The Most Dangerous Man in Europe”: Otto Skorzeny Between Myth & History

As Skorzeny frantically tried to track the latest movement of the Italian dictator, on September 8, 1943, Brigade General Giuseppe Castellano and Major General Walter Bedell Smith signed the Armistice of Cassibile. On September 8, General Dwight D. Eisenhower announced from Algiers: “Hostilities between the armed forces of the United Nations and those of Italy terminate at once. All Italians who now act to help eject the Germany aggressor from Italian soil will have the assistance and support of the United Nations.” Adolf Hitler, who had been increasing the German forces stationed in Italy, ordered the immediate invasion of the peninsula from the North.

A few days after the armistice was signed, Skorzeny finally discovered that Mussolini was at Hotel Campo Imperatore on the Gran Sasso. The building was on a plateau rising more than 5,000 feet above the ground. A cable car connected it to the nearest village. Because the lofty terrain made a direct attack impossible, General Student and Major Mors opted to approach the location from the air.

On September 12, a paratrooper squad flew from Pratica di Mare airport to Gran Sasso in their gliders. A second group, headed by Major Mors, secured the cable car station at the foot of the mountain, allowing the paratroopers to rely on the element of surprise. Otto Skorzeny was the first to successfully land near the hotel, quickly followed by the other soldiers. The Italian garrison guarding Mussolini surrendered without firing a single shot.

“Duce, the Führer has sent me! You are free,” Skorzeny told the Italian dictator. The SS officer and Mussolini left Gran Sasso on the “Storch” plane flown by Heinrich Gerlach, General Student’s personal pilot.

After the successful completion of the mission, Nazi propaganda hailed Otto Skorzeny as a hero. Adolf Hitler promoted him to Sturmbannführer and awarded him the Knight’s Cross. As news of the Gran Sasso Raid spread through Europe, he reached legendary status, even among the Allies. During a speech at the House of Common, Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the operation as “a daring attack.” Otto Skorzeny gained the reputation as “the most dangerous man in Europe.”

Over time, contrasting narratives and myths around the raid began to form. English historian Sir William Deakin defined the operation as “both intricate and confused, and also obscured by the personal vanity of certain of the direct participants.” In his memoir, Otto Skorzeny claimed that Adolf Hitler personally gave him the task of planning the entire operation: “I’m entrusting to you the execution of an undertaking which is of great importance for the future of course of the war,” the Nazi leader allegedly declared. However, General Student and Major Mors refuted Skorzeny’s narrative, asserting that the SS officer only played a minor role in the raid.

The Aftermath of the Gran Sasso Raid

Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels depicted the Gran Sasso raid as confirmation of the professionalism of the German forces, able to effortlessly perform even when suffering strategic setbacks. In this sense, Otto Skorzeny became the embodiment of the ideal Nazi soldier, an exemplary combination of ideological commitment and military acumen.

A newsreel of Adolf Hitler greeting Benito Mussolini at the airport of Rastenburg showed the German population and the Allies the successful outcome of the raid. The fall of the regime and his subsequent arrest, however, had affected Mussolini’s boastful personality.

“The Duce has not drawn the moral conclusions from Italy’s catastrophe that the Fuehrer had expected from him,” remarked Goebbels in his diary. After all, Mussolini was “nothing but an Italian and can’t get away from that heritage,” scornfully added the Minister of Propaganda.

Despite some initial low morale, the Duce eventually agreed to Hitler’s plan to reinstate the Fascist regime in Italy. On September 18, Mussolini announced the establishment of the Italian Social Republic, a new Fascist state based in Salò, a town on Garda Lake. Until the end of the war, the Republic of Salò supported Nazi Germany’s fight against the advancing Allied forces and the Italian partisans, thus prolonging the hostilities on the Southern front.