When one hears the name Grant Wood you might recall overalls, country farmland, traditional Americana, and of course American Gothic. Critics, viewers, and even Wood himself projected this image, yet this is a flat representation of Wood. His many other works showcase a talented, observant, and introspective man that had opinions and views on America during some of its most challenging times. He gave Midwestern artists a voice to showcase their viewpoints whereas it was the norm to look towards New York City, London, or Paris in the art world. Grant would use his art to portray his perception of the American Midwest, its people, and his ideas of the American Legacy in his art.

Grant Wood And Impressionist Art

Before Grant Wood created sweeping landscapes in the Regionalist style he started out as an Impressionist painter. Wood made several trips to Europe, including France, where he took classes at the Académie Julian in Paris. Similar to the Impressionist artist Claude Monet, they both studied the colors and light of the natural world to create works during different seasons, times of day, and places. By comparing the painting Calendulas (seen above) with Monet’s Bouquet of Sunflower painting, we can see how the Impressionists’ subject matters influenced Wood on the types of objects he painted. With this painting, Wood uses yellow flowers set in a vase as Monet did. However, his use of a geometric background and his sharper use of line and detail make his interpretation more realistic. Later in his career Wood became more interested in creating works that had rounder and more gestural forms that focused on attention to detail rather than painterly brushstrokes.

Even though Wood stopped creating Impressionist paintings, his later works still show influences of the style. Like Monet, Wood would paint the same scene in various seasons and during different times of the day. This early representation of nature would lay the groundwork for his later paintings of the Iowa landscape. Compared to Monet’s haystack paintings, Wood’s strong contrasts between light and shadow create forms that are more three-dimensional rather than flat and two-dimensional. The rows of corn shocks reach further and further into the background creating a perspective that reaches far off towards the end of the painting. Impressionists used texture to create hazy indistinguishable backgrounds whereas Wood’s are well defined. His use of diagonal angles from the tops of corn shocks to the rows of these stacks creates a more dynamic and theatrical interpretation of simple corn shocks. They are a nod towards Wood’s nostalgia of his childhood as he painted this a year before his death.

Wood’s All-American Approach To Realism

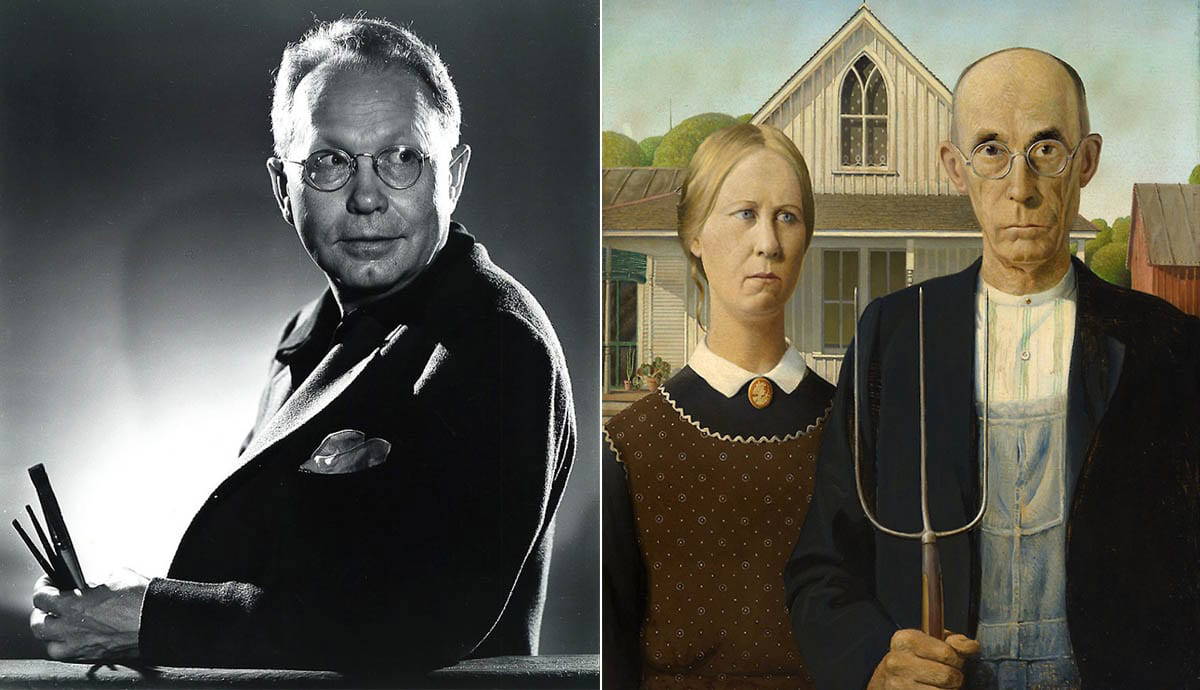

Grant’s trip to Munich, Germany had a lasting impact on both his stylistic and ideological approach to art. The Renaissance paintings of Northern Europe and their approach to portraiture influenced Wood to create more realistic representations of people. He studied painters such as Jan Van Eyck or Albrecht Durer, noticing how they painted everyday people in ordinary situations. This greatly influenced Wood on his return back to Iowa, and he started painting scenes and portraits of people whom he had seen throughout his life. His intentions were not to create caricatures of Midwestern people or stereotype their lives. To Wood, these were the people he knew, and he painted the versions of people he saw rather than what others thought they should be.

Similar to American Gothic this painting titled Plaid Sweater features an archetype of the “All-American,” in this case, a boy. Grant painted the boy in a typical football getup instead of placing him in a suit and tie. Other portraits during this time would be staged with children dressed in their Sunday best, which were not accurate representations of a child’s everyday life. Both portraits also feature a natural landscape in the background instead of props and displays like traditional portraits. His influence by Northern Renaissance Portraiture is evident because of his attention to detail. From the fine lines of the boy’s hair, the plaid pattern of the sweatshirt, and the creases in his paints there is strong attention to every single strand and thread. His technical ability to have everything in its proper place and create accurate details further showcases his determination to truthfully portray the people he painted.

Regionalism And The Iowan Landscape

Grant Wood was one of the first artists to promote and create art in the Regionalism movement. Wood and his contemporaries strived to create art that was uniquely American. It is both ironic and intriguing that in this struggle he was influenced by European styles from the Renaissance to Impressionism. An example of his use of Regionalism is his painting The Birthplace of Herbert Hoover, depicting the home where the president was born in West Branch, Iowa. Wood painted this before the house became a landmark, and it is located near where Wood grew up. By painting and naming this specific scene he is predicting its historical importance and creating a tie between rural America, the presidency, and even himself.

Wood uses his signature bird’s eye view perspective so that the viewer feels as if he or she is looking down upon the scene rather than at an eye level. The perspective is so zoomed in that the viewer can see each individual tree leaf and even tiny acorns placed at the very top of a tree. His scenes are similar to miniature reproductions of towns and it creates a dream-like appearance even though he is depicting real places. His trees are enormous compared to the homes he illustrates, emphasizing how nature dominates over the homes and people. He idealized the countryside and disliked the large urban settings, using Regionalism as a way to depict the contrasts between man and nature. Regionalism was used as a way to not only depict life in the country but to give voices to those who did not have one in cosmopolitan cities.

This painting titled Young Corn illustrates the land Wood grew up surrounded by his entire life and his inclination to paint rural areas. Midwestern landscapes are dubbed as being “flat”, yet in Wood’s paintings, they are anything but. Wood starts out with the viewer having to look out from the top of a hilly field, which then veers upward towards the horizon creating a disorienting effect. His hills look like the tracks of a roller coaster going up and then down and his landscapes have a dominating and assertive presence. The waves of the hillside show supremacy of nature over the tiny houses and people. His trees are bulbous figures that are circular in shape, and these enlarged shapes of the trees further reinforce the notion that the nature of the countryside is dominant and man-made objects are almost obsolete compared to them.

Wood’s interpretation of the Midwestern landscape and its people was a record of what was left behind. The traditional way of rural life was largely disappearing along with the rural landscape itself. With the rise of industrialized cities, Wood’s paintings have become a record of what life was like during his time. They are nostalgic because his landscapes look like something from a daydream, but they also showcase the realities of people’s lives in rural towns. His paintings portray real images of his childhood, and they became a way for him to hold onto those sentimental memories. With this perspective, his works are melancholy in the hopes that civilization would return to their roots of being an agricultural nation.

American Myths And Legends Told By Wood

In addition to his landscape paintings, Wood created American imagery that contained satirical and political themes. Parson Weems’ Fable depicts Parson Weems himself pulling back a curtain to show a depiction of his tale of George Washington cutting down a cherry tree and not being able to tell a lie. Wood utilizes this image to literally “pull away the curtain” and showcase the reality behind the myth.

One way Wood does so is by comically putting an adult George Washington head on a boy’s body, which blends the myth of his childhood with the reality of his adulthood. This child is a rendition of the Gilbert Stuart portrait of the president, making it the most recognizable and, therefore, a patriotic image of the first American President. Wood undercuts this fable with reality. Behind the myth of the cherry tree are two slaves in the background to show that Washington did own slaves during his life. Wood uses a diagonal line almost identical in placement as his January painting to point the viewer towards them, which are off in the distance at another cherry tree. He also uses this perspective to veer the viewer towards the darkness foreboding on the horizon.

According to Wood, he only ever did one satirical painting, and it is the one shown above. It all started with a stained glass window that Wood was commissioned to create for the Veterans Memorial Building in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Wood traveled to Germany to learn how to construct the window and spent over a year there. Because of its construction in Germany and America’s previous conflicts with Germany during WWI, the memorial had no dedication ceremony because of complaints, particularly by the local Daughters of the American Revolution. Wood took this as a slight towards his art and took revenge in the form of his painting Daughters of Revolution.

It depicts three DAR members standing smugly and proudly in front of a reproduction of Washington Crossing the Delaware. They are dressed aristocratically with lace collars, pearl earrings, even holding an English teacup. These English inspired articles are a direct contrast to the very nobility that their forefathers fought against. To Wood, they represent an aristocracy in America benefitting socially off of the relationship of their ancestors. What makes this piece ironic is that the German-American painter, Emanuel Leutze, did the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware.

After the Depression and with the start of World War II, American iconography was increasingly popular to rejuvenate patriotism. Wood was able to straddle this line delicately by showing the hypocrisy of people and their false appearances in the face of reality. His paintings are comical, yet contemplative because he is not trying to be anti-patriotic in these works, but rather to have viewers come to terms with the past rather than hide from it.

Grant Wood’s Contribution To Schools And Teaching

When students walk through the foyer into Parks Library and up the stone stairs they come face to face with the largest murals Wood ever created. The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was created as part of the New Deal, which gave artists opportunities to work in public art. Wood was commissioned by Iowa State University to create a series of four murals, which still reside at Parks Library on the Iowa State campus. They contain themes of agriculture, science, and home economics and are meant to reflect the university’s history in education of the Midwest. Wood designed the murals and oversaw everything from the color palette to the actual construction/application.

Like his other paintings, these emphasize the lives of Midwesterners at the time. He chose to showcase their humble beginnings in When Tillage Begins to technological advancements being made in Other Arts Follow, shown in the image above. These panels are also examples of his dedication to embracing Midwestern artists as he employed artists who showed work at the Iowa State Fair, as well as artists with whom he worked and taught at the Stone City Art Colony.

While there are visible records of Wood’s work at Iowa State, there are virtually none at its competitor, The University of Iowa, where Wood himself was a professor. His appointment as director of the Iowan PWAP and associate professor of fine arts was met with skepticism and resentment. Wood had no college degree and no experience teaching at the college level. That, along with his fame and recognition, stirred controversy during his stay in Iowa City. Peers saw his style as “folksy” and “cartoonish” rather than fine art. The University was leaning more towards European influences of abstraction and expressionism and was less enthusiastic about Wood’s promotion of Regionalism. All of these factors, and the assumptions of his closeted homosexuality, created conflicts among Wood and some of his colleagues. Ultimately, his failing health led to Wood not returning to teach.

Wood preferred a more direct approach to teaching compared to traditional academic instruction. He worked to establish the Stone City Artist Colony, which strived to give residency and support for Midwestern artists. His passion for teaching would have stemmed from his experiences as a child. He had support from his own teachers and community in his artistic endeavors. In Wood’s own way, his mentoring and wanting to teach other Midwestern artists stemmed from this. Wood’s artworks are still owned by Iowan/Midwestern museums and schools making his work accessible for the people he created it for. His dual roles of artist and teacher are remembered by the several schools and educational systems named after him, continuing his legacy as a Midwesterner and Iowan.