Exploring Aboriginal history can be intimidating, particularly if you are not familiar with the subject matter. Aboriginal Australians, a book authored by historian Richard Broome, provides a detailed account of the history of Aboriginal people since the arrival of the Europeans. In The Original Australians, Josephine Flood complements Broome’s work by discussing the history of pre-contact Aboriginals. However, it is important to note that both Broome and Flood are non-Indigenous historians, and their approach is inevitably influenced by their Western education and methodology.

Aboriginal authors Victor Steffensen and Bruce Pascoe offer an Indigenous perspective on the history of Indigenous Australians in their books, Fire Country and Dark Emu, respectively. Finally, Robert M.W. Dixon shines a light on the complexity of Aboriginal languages in his book, The Languages of Australia.

1. Richard Broome’s Aboriginal Australians: A History Since 1788

Richard Broome, Emeritus Professor of History at La Trobe University, is an authority on Aboriginal history. He taught at La Trobe from 1977 to 1981 and was appointed Associate Professor in 1992, one year after being chosen as a consultant to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. His commitment to doing justice to Aboriginal history is reflected in his most comprehensive work, Aboriginal Australians: A History Since 1788. The book was first published in 1982, republished in 1994 and 2002, completely rewritten in 2010, and revised for a fifth edition in 2019.

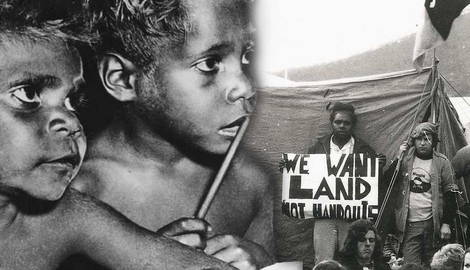

The 15 chapters that constitute Aboriginal Australians detail the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders from the time of James Cook’s arrival in Botany Bay in 1788 (“The Eora confront the British”) to their (often overlooked) cultural and physical resistance against Western influence and culture.

The book discusses the penetration into what is now Queensland and the Northern Territory (“The Age of Race and Northern Frontiers”) and the significant role that Aboriginal stockmen played on cattle stations in the 20th century (“Working with Cattle”). The latest edition of the book covers recent Aboriginal history and activism, from the 2007 Intervention (also known as the Northern Territory National Emergency Response) to the 2017 petition from First Nations demanding constitutional amendments to protect their rights, known as the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Aboriginal Australians is a great book to read. Broome has a way with words and some passages are quite poetic. Here, for instance, Broome describes the European penetration of Australia: “Unlike the Eora, who were surprised by sails from nowhere, Aboriginal groups inland were forewarned of invasion (…) Detailed information about European explorers preceded them by hundreds of kilometres along Aboriginal tracks. Distant groups learned of pale, ghost-like strangers, weird animals and baggage, which proved to be loaded drays, horses and stock” (p. 52).

Broome shows us that the history and culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders neither ended nor started with the coming of Europeans in 1788. Instead, they adapted to the massive upheavals triggered by colonialism and evolved.

2. Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Agriculture

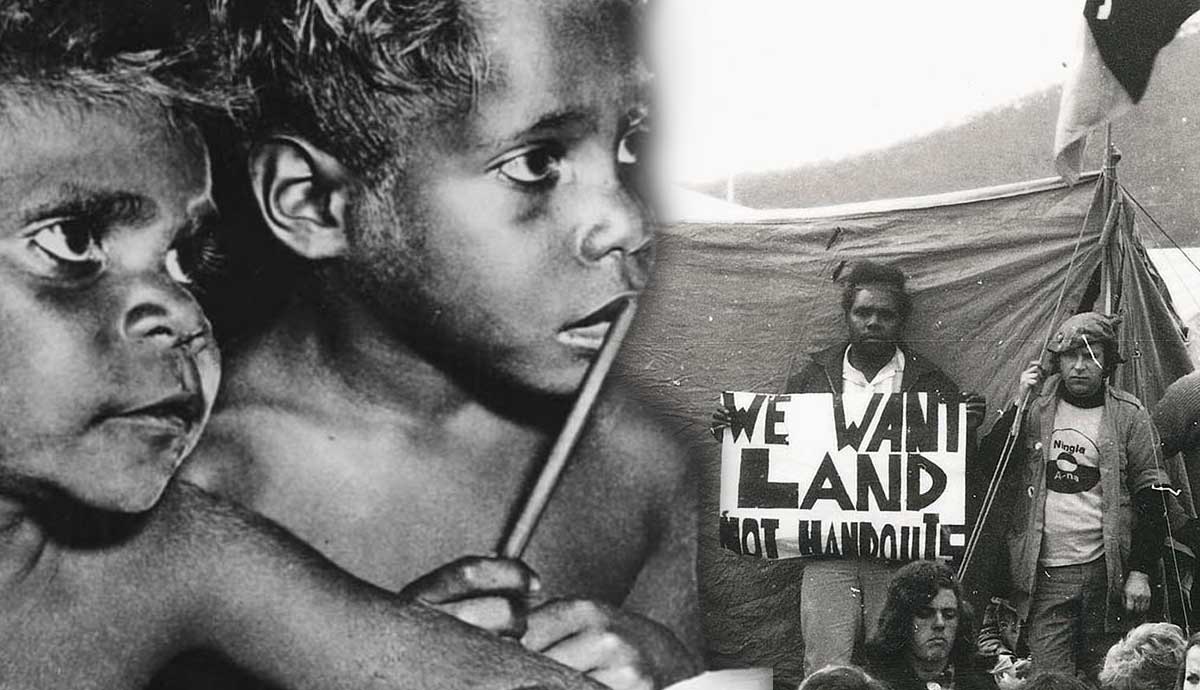

When Dark Emu was published in 2014, it was met with severe criticism. Even after a decade, it remains controversial. For centuries, Western history has staunchly portrayed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as mere hunter-gatherers, incapable of harvesting, planting, or manipulating the surrounding landscape for their benefit. This is the core of the terra nullius theory which for centuries has justified the theft of Aboriginal lands. It is also a self-serving portrayal of Aboriginal people, as it allowed European explorers to claim their lands. It was not only their right to claim it: it was their duty.

Pascoe’s book, a must-read for anyone interested in learning more about Aboriginal history, convincingly challenges this view. Pascoe uncovered evidence that his ancestors were more than just hunter-gatherers, that long before the coming of Europeans, people across Australia were actively manipulating the landscape by building fish traps and dams, planting crops, irrigating, and storing food surplus in sheds and houses.

The journals and diaries of many early explorers, too often “full of their surprise at finding evidence of Aboriginal utility of the land” (p. 55), documented the presence of dams, wells, and irrigation trenches. As Pascoe points out, the evidence regarding pre-contact Aboriginal knowledge is available to anyone as it is part of what we usually call “Australian literature.” Ironically, it is precisely thanks to the diaries and journals of European explorers that scholars are now able to deconstruct assumptions about Aboriginal people and conduct a revision of Australian history.

To put it in the words of Pascoe, “Australians make plaster figurines of Aboriginal men standing on one leg, spear in hand, waiting for the windfall kangaroo, while we have all but ignored ethnographic evidence of Aboriginal engineering” (p. 87). The Brewarrina fish traps, also known as Baiame’s Ngunnhu, a complex, half-a-kilometer-long system (0.3 of a mile) of stone walls in the Barwon River in New South Wales, exemplify the level of Aboriginal achievements.

3. Josephine Flood’s The Original Australians, the Story of the Aboriginal People

The Original Australians by Josephine Flood delves into the history of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders, both prior to and after the arrival of Captain Cook. Unlike Broome, Flood is not only a historian but also an archeologist (and former director of the Aboriginal Heritage Section of the Australian Heritage Commission). By drawing on archeological evidence, Aboriginal myths, and Dreamtime stories, her book is a powerful tribute to the “oldest continuous culture on Earth.” It is also an ode to the Australian continent, its incredible landscapes, its desert claypans, gorges, caves, and rock formations.

Flood earned her BA degree from the University of Cambridge, and later completed her MA and PhD at the Australian National University. She was the first European to participate in the excavations of the Cloggs Cave in Victoria, near the town of Buchan on the ancestral lands of the Gunaikurnai nation.

Between 1981 and 1992, she led several expeditions to study and document rock art in Queensland, in the Cape York region, and the Northern Territory. Each chapter of The Original Australians, published in 2006, is dedicated to a specific moment or period in Aboriginal history, with the title summarizing it for us. The first chapter, for instance, is titled: “Exploration: European discovery of Australia.” We then have “Colonisation: Early Sydney,” “Confrontation: Early Tasmania and Victoria,” and so on, until the final chapter, “Resurgence: The story continues.”

The sixth chapter focuses exclusively on pre-contact Aboriginal people. It discusses various theories surrounding their origins (without ever disregarding Aboriginal claim that “they’ve always been there”), the importance of Dreamtime Stories in Aboriginal culture, the role of Indigenous women before and after contact, as well as the emergence of the Aboriginal dot painting movement in the early 1970s, a movement which is, Flood argues, the direct “development from ceremonial ground mosaics made from pellets of white clay or black charcoal, feathers, pebbles and chopped leaves and flowers of the native daisy and other plants coloured with powdered red or yellow ochre” (p. 290).

4. Victor Steffensen’s Fire Country

“The knowledge is in the landscape,” Victor Steffensen states in his groundbreaking book Fire Country — How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia, published by Hardie Grant in 2020 during the Australian Black Summer. Steffensen, who has German and English heritage from his father’s side and Tagalaka (or Tagalag) through his mother’s, is the co-founder of the Firesticks Alliance and the National Indigenous Fire Workshop. With Fire Country, he established himself as the face of Indigenous land management through fire.

Steffensen’s book looks to the future as much as it looks to the past. On the one hand, it is the culmination of years spent listening and carefully learning from Dr. George Musgrave and Dr. Tommy George, two Awu Laya Elders from Laura, in the Cape York peninsula. On the other, the writing of Fire Country stems from the decades Steffensen spent “on country,” working with the Firesticks Alliance to educate Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike about the importance of cultural burning.

Fire Country, just like Dark Emu, is a book for everyone, for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike. It is both a memoir (Part one is titled “Finding the Old People”) and an educational book (Part Two, “The Fire” offers extremely precise technical advice about the different types of land, the correct seasons for lighting fires, and the dangers of hot fires). It is also a tribute to the importance of Aboriginal Elders and the role they can still play in Australian society. Musgrave and George are, after all, two “walking encyclopedias,” as he calls them.

Australia’s fear of fire, Steffensen implies, is directly connected to Australia’s disregard for Indigenous traditional knowledge. For decades, Indigenous Australians were prevented from applying the regime of cultural burns of their ancestors on the lands of their ancestors. They were staunchly prevented from “sharing the fire knowledge” (which is also the title of the book’s fourth part), and Steffensen devotes an entire section (Part Three, “The Other Side”) to discussing the obstacles faced by Indigenous communities across Australia when it comes to cultural burning. Overall, Fire Country is a powerful call to respect and learn about Aboriginal culture and we can all benefit from reading and studying it.

5. R.M.W. Dixon’s The Languages of Australia

The above-mentioned books fail to comprehensively address one important topic in the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Aboriginal languages. Robert M.W. Dixon devoted his whole life to (historical) linguistics. Over the years, he has written and published grammars of many Aboriginal languages. In 1964, for instance, he undertook fieldwork in northeast Queensland, focusing especially on Dyirbal, the Pama-Nyungan language spoken by the Dyirbal (Jirrbal) nation from northern Queensland. Unfortunately, Dyirbal is now on the verge of extinction.

Over the years, Dixon has studied several other extinct languages, mostly from Queensland, such as the Nyawaygi (spoken by the Nyawigi people from the area around Townsville), the Mbabaram (the language of the Mbabaram tribe from southwest of Cairns), Warrgamay (similar to Dyirbal and spoken in a vast area in northeast Queensland) and Yidiny (the language, now classified as nearly extinct, of Aboriginal tribes from Cairns and the Tablelands Region).

The Languages of Australia is both comprehensive and very specific. Readers will find all they need to know about Aboriginal languages, beginning with the fundamental difference between the so-called Pama-Nyungan (PN) and non-Pama-Nyungan languages. Dixon further discusses the characteristics of proto-Australian, the ancestral Aboriginal language all Indigenous languages in Australia can be traced back to; the practice of language switching (the changing of register required by specific social situations); the importance of “respect” speech varieties, as well as the number of Aboriginal languages spoken before colonization (which oscillates between 300 and 700).

More than four decades after it was published, The Languages of Australia remains a pioneering work and a testament to the passion of an Englishman from Gloucester for Aboriginal languages, culture, and history.