The British Empire and the Russian Empire engaged in intense competition for control over Central Asia for most of the 19th century. The Great Game, a term for the British plan to safeguard its colonial jewel, India, against Russian influence, was full of diplomatic and political maneuvers and confrontations. For Tsarist Russia, British commercial and military advancements in Central Asia disturbed its goals of territorial expansion, aimed at creating one of the largest land-based empires in the world. Afghanistan, neighboring the Russian Empire, became a focal point in the British policy of containment of Russian expansion. Seeking the neutrality of Afghanistan, the British officials aimed to establish it as a “buffer” zone to limit Russian expansion in India. The Great Game resulted in proxy wars, including the First and Second Anglo-Afghan Wars, shaping the geopolitical landscape and making Central Asia a key geopolitical point in the future.

Origins of the Great Game in Afghanistan

Central Asia had been the chessboard of the competition between the British and Russian Empires since the 18th century due to its geopolitical location. Being at the crossroads of civilizations and the Silk Road trading route, Central Asia is often referred to as a heartland. The term was coined by the British geographer Halford Mackinder in the early 20th century, who stated that gaining control over Central Asia was a key aspect of world dominance.

Beginning in the 19th century, both the British Empire and the Russian Empire realized that acquiring economic and political influence over Central Asia was necessary to achieve their goals of territorial expansion and world dominance.

The reasons behind the Russian Empire’s intention to expand southward into Central Asia were economic, political, and cultural. Central Asia’s strategic geopolitical location and easy access to the major trading routes made it an attractive market for Russian goods. In addition, the Russian Tsars perceived the expansion of Russian political and cultural influence as their civilizing mission for the tribal communities of Central Asia, similar to the American notion of Manifest Destiny.

Russian expansionist policy also focused on preventing the British East India Company’s dominance in the region. With this objective, the Russian Empire launched its initial offensive on the Khiva and Bukhara Khanates (both located in present-day Uzbekistan), which border Afghanistan. Even though these khanates showed unexpected resistance and Russia was twice defeated in 1717 and again in 1839–1840, Russia still managed to exercise considerable socio-political influence over these lands through a series of military campaigns. By the 1870s, both Khanates had officially become protectorates of the Russian Empire.

On the other hand, the British Empire saw the growing Russian Empire as a threat to its economic and imperial interests, notably in India. During the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, Britain solidified its dominance in India. Tsarist Russia’s control over the khanates and tribes near its southern border and the possibility of reaching Afghanistan was concerning for British officials, as Afghanistan was the gateway into India. The British Empire envisaged forming Afghanistan as a buffer zone to address the issue, which would eventually contain Russian expansion in India.

Coining the Term “The Great Game”

By the beginning of the 19th century, the internal socio-political environment of Afghanistan also provided the ground for foreign powers to utilize their powers. The local rulers of the Durrani dynasty’s incompetence, power struggles, and dynastic conflicts made Afghanistan vulnerable to foreign powers’ policies. The British Empire and the Russian Empire successfully exploited Afghan rulers’ weaknesses, pitting Afghanistan against itself to achieve their strategic aims. In another explanation, in his book, I Luoghi della Storia, former Ambassador Sergio Romano wrote:

“The Afghans spent a good part of the nineteenth century playing a diplomatic and military game with the great powers—the so-called ‘Great Game’ the main rule of which was to use the Russians against the Brits and the Brits against the Russians.”

British intelligence officer Arthur Conolly coined the term in the 19th century to describe the complex nature of the confrontation between the two empires. Famous English novelist Rudyard Kipling, however, popularized the term in his book Kim, published in 1904. Kipling used the term “Great Game” to describe the struggle between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire for control of India as a colony.

Evgeny Sergeev, a professor of history at the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of World History, characterized the Great Game as a proto-Cold War between East and West. It created an environment of distrust and the constant threat of war between the British and Russian empires.

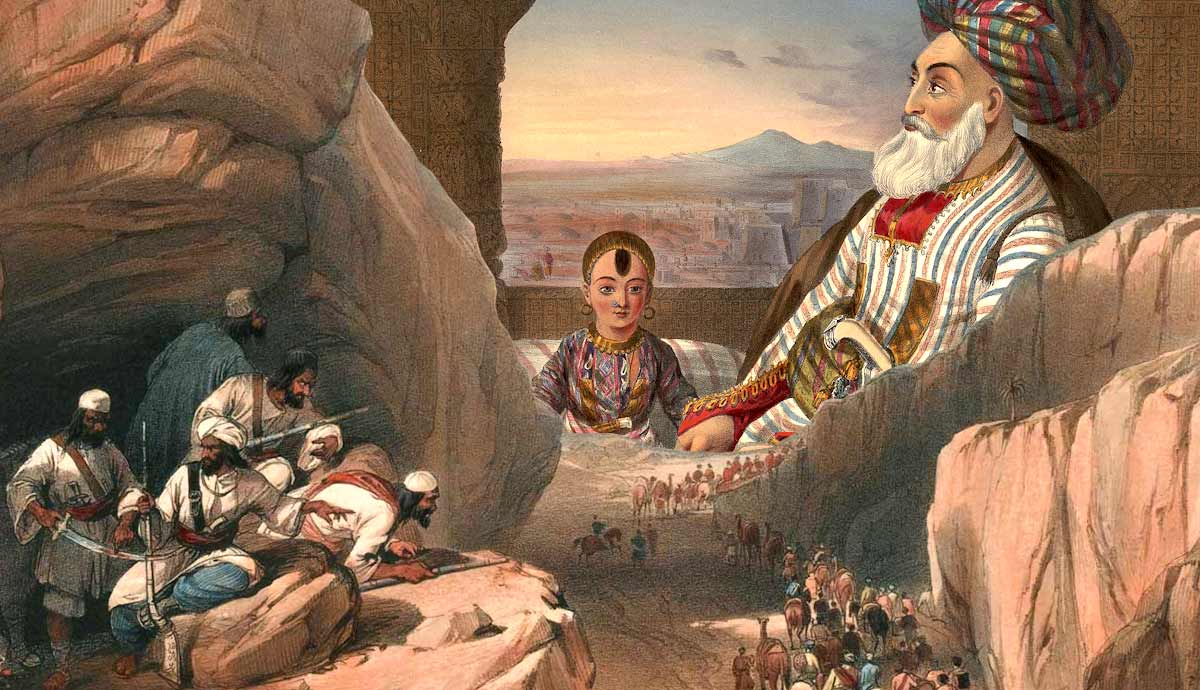

The First Anglo-Afghan War

The Great Game resulted in three Anglo-Afghan wars throughout the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. The first Anglo-Afghan War, fought from 1838 to 1842, was the British attempt to deter growing Russian influence in Afghanistan in order to protect British India from Russian influence.

In 1826, Dost Mohammad Khan from the Durrani dynasty became the new ruler of Afghanistan. During this period, Afghanistan fought against the Sikh Kingdom for Peshawar, an important center for trade with West and Central Asia. Dost Mohammad Khan formed close ties with the Russian Empire, hoping to get financial and military assistance to counterattack the Sikhs.

The British East India Company authorities were alarmed by the developments and employed envoys to Kabul, Afghanistan, demanding to halt the cooperation processes with Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. Dost Mohammad Khan demanded the return of Peshawar to Afghanistan. The British Empire, however, denied it, as the British did not consider their stance in the region powerful enough to oppose the Sikhs, triggering the invasion of Afghanistan and the start of the First Anglo-Afghan War in 1838. The invasion aimed to restore the exiled former ruler of Afghanistan, Shah Shoja. The plan materialized after capturing the fortress of Ghazni in 1939 and entering the city of Kabul. Dost Mohammad Khan was forced to flee to Balkh and then Bukhara and was eventually captured there.

The same year, an uprising against the growing British influence in Afghanistan broke out. Dost Mohammad managed to escape from prison and joined the rebellion. However, by 1840, he was defeated, and the British officials exiled the former ruler and his family to India.

Despite the British Empire’s early victory in the First Anglo-Afghan War, British forces found it difficult to put an end to the uprisings, which were frequently hostile and with heavy casualties from the British side. Hence, the majority of the English military left Kabul in 1942. Shah Shoja, the British-installed ruler, was brutally assassinated by Afghan uprisings, as he did not enjoy popularity either. Lord Ellenborough, the governor-general of India, announced Dost Muhammad Khan’s restoration to the throne and the British withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1843.

Between Wars: British “Policy of Masterly Inactivity” in Afghanistan

Even though the First Anglo-Afghan War resulted in the British defeat and withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Treaty of Peshawar, signed in 1855 between British India and Dost Mohammed of Kabul, solidified British influence in Afghanistan. The treaty dictated a policy of non-interference, particularly with the Russian Empire, and the restoration of friendly cooperation between the two parties. It also proclaimed Afghanistan’s and the British Empire’s territorial integrity. Dost Mohammed showed loyalty to the treaty’s stipulations, refusing to assist the rebels against the British Empire during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Following the death of Dost Mohammed in 1863, Lord Lawrence, the governor-general in India, initiated the policy of masterly inactivity in 1864. Simply put, it meant that the British Empire would not interfere in the internal affairs of Afghanistan but would closely watch its foreign policy.

Adhering to this policy, the British Empire did not interfere in the wars of succession between the 16 sons of Dost Muhammad. Lord Lawrence accepted different rulers during different times, based on who would succeed in capturing the throne. Finally, in 1868, Sher Ali became the new ruler of Afghanistan. Lawrence accepted him and provided Afghanistan with military and financial help. However, he did not formalize the partnership. The policy did not enjoy greater support, especially from Sher Ali, who once remarked, “English look to nothing but their own interests and bide their time.” The discontent drifted Afghanistan’s new leader towards Russia, triggering the start of the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

The Second Anglo-Afghan War

In July 1878, Amir Sher Ali permitted the Russian delegates to enter Kabul. Amir Sher Ali’s decision was motivated by the desire to maintain Afghanistan’s sovereignty during the Great Game. By allowing the Russian mission into Kabul, Ali strived to achieve a balance between the British and Russian Empires. Threatened by the Russian presence in Afghanistan, the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, initiated a diplomatic mission to Kabul in August. Unexpectedly, Sher Ali refused to meet the British officials, and the mission was turned back at the eastern end of the Khyber Pass.

Lord Lytton decided to act, and by November 1878, approximately 40,000 British soldiers invaded Afghanistan, marking the start of the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Initially, the forces of the British Empire achieved success, and Amir Sher Ali was forced to flee Afghanistan. Mohammad Yaqub Khan, a British-friendly successor, took the throne. The Treaty of Gandamak was signed on May 26, 1879, ending the conflict by restoring the British diplomatic mission in Kabul, led by Sir Louis Cavagnari.

However, peace appeared short-lived. On September 3, members of the mission were brutally massacred by Ayub Khan, brother of Amir Mohammad Yaqub. The British forces defeated Ayub Khan and installed a new Amir, Abdur Rahman Khan, by September 1880. Loyal to the British Empire, a new ruler gave the British Empire full access to determine Afghanistan’s foreign policy and to form a buffer zone between British India and the Russian Empire in exchange for protection and a subsidy.

The Joint Boundary Commission & the Durand Line

To define the northern border between the British and Russian Empires, members of a joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission in Afghanistan traveled and documented the northern border area of Afghanistan during the years 1884–1886. The commission declared a permanent British-Russian border along the Amu Darya River. Even though Amir Abdur Rahman Khan’s representatives were present in the commission, they acted as bystanders only and were denied any right to participate in the demarcation processes. Amir Abdur Rahman Khan wasn’t given the chance to determine the boundaries of his country until almost ten years later. The border between British India and Afghanistan, which is now the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, was drawn in 1893 as a result of an agreement between Abdur Rahman Khan and Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, a secretary for the British Indian administration.

The borderline became known as the Durand Line, cutting through the Pashtun-dominated tribal areas and splitting one of the world’s largest tribal societies into two. It has been a source of contention between the two countries for more than 100 years. The Durand Line illustrates how the great empires’ competition for influence shaped the future of numerous people.

The End of the Great Game in Afghanistan

International developments in the early 20th century eventually ended the Great Game. The Russian Empire was financially and militarily depleted by the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1906), and it appeared that Tsar Nicholas II could not finance the Central Asian proxy wars. After the Anglo-Russian Convention was signed on August 31, 1907, the Great Game was formally over. With the acquisition of Afghanistan as its protectorate, the British Empire won an almost century-long confrontation with the Russian Empire.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the two empires stood together against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire). As World War I was fought on the European continent and demanded immense financial and military resources, the British Empire and the Russian Empire did not have the capacity to continue the rivalry in Central Asia.

The Great Game involved the present-day nations of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran, and the repercussions of this historical rivalry can still be seen in the socio-political challenges that Afghanistan and its neighbors face today. Afghanistan’s ruler, Abdur Rahman Khan, noted in 1900,

“How can a small power like Afghanistan, which is like a goat between these lions or a grain of wheat between two strong millstones of the grinding mill, stand in the midway of the stones without being ground to dust?”