By the common era, the Greek term mythos had come to mean “fable, or fiction” rather than its original definition: “report, narrative, or a story with historical substratum.” As a result, historians have used the term “myth” to mean “fable” throughout history. Hence, the traditional Greco-Roman usage of the word “myth” is disparaging, and the phrase “Greek mythology,” as employed in academic discourse today, may incorrectly imply that all ancient narratives are simply that. However, all these tales had at least some connection with the real world in which the ancients lived. Myths were often invoked to make sense of the world, deepening the connection of the people with their surroundings and fostering a sense of a common identity rooted in myths and legends. Here are four real-world locations of Greek Mythology.

1. The Minotaur and the Palace of King Minos in Greek Mythology

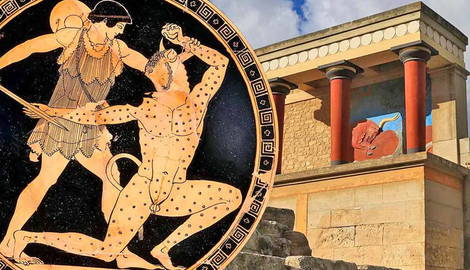

Theseus and the Minotaur is one of the most recognized dyads in Greek mythology and for good reason. The unnatural offspring of Queen Pasiphae — wife of King Minos of Crete — and a bull sent by Zeus, the Minotaur was a half-man and half-bull hybrid that terrorized the Athenians. But how did this horror story come to be?

Embarrassed by the spectacle of his wife giving birth to such a terrible beast, Minos commissioned Daedalus, the legendary craftsman, to construct an inescapable labyrinth at the Palace of Knossos and place the Minotaur within it. Rather than killing the creature, Minos found quite a devilish use for it by placing his imprisoned enemies in the labyrinth and forcing them to face the terror that was the Minotaur. Minos’ use of the Minotaur only worsened after the death of his son, Androgeus, by a bull in Athens. Demanding retribution, Minos required the king of Athens, Aegeus, to submit seven men and women to serve as sacrifices for the Minotaur in the labyrinth. By the third year of annual sacrifices, Theseus, son of Aegeus, volunteered as tribute with the full intention of slaying the Minotaur once and for all.

Theseus managed to not only kill the Minotaur, but he also escaped the labyrinth with the use of a ball of yarn (given to him by Princess Ariadne). Having defeated the Minotaur and saved the Athenians, Theseus sailed back to Athens with Ariadne in his arms. So, is there truth behind the strange tale of Theseus and the flesh-eating Minotaur?

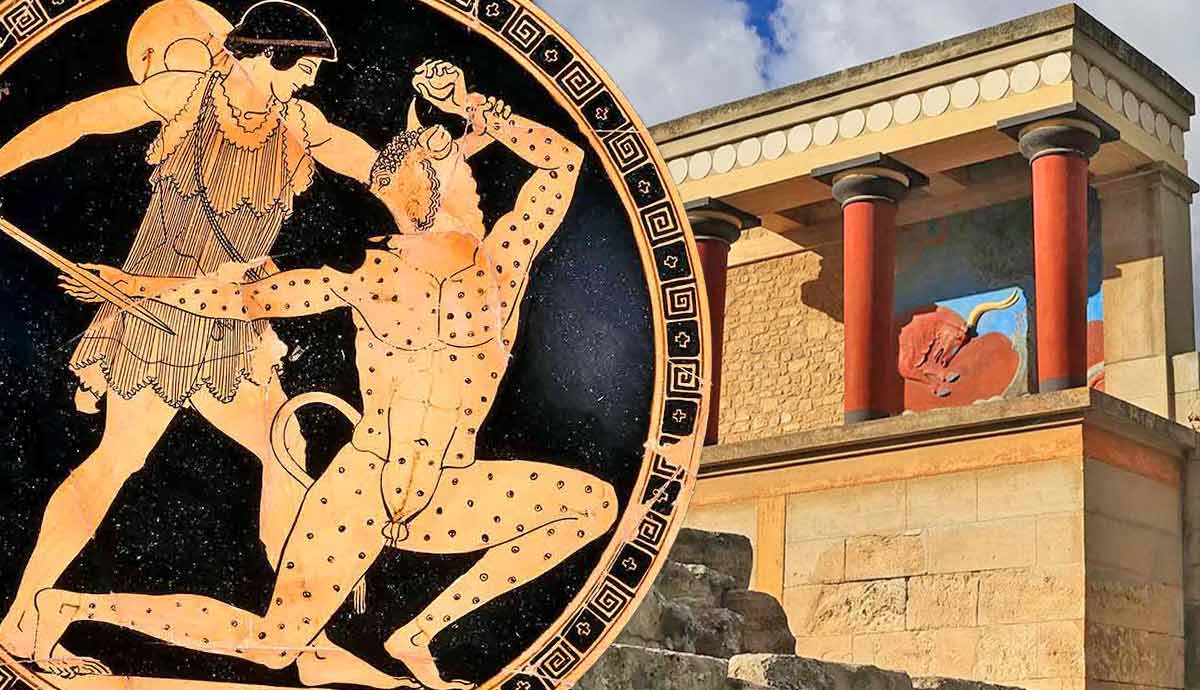

More than a millennium before the first recorded story of the Minotaur, there existed a Bronze Age civilization on the island of Crete. In 1899, following Sir Arthur Evans’ discovery of the Palace of Knossos on Crete, these people were given a name, the Minoans.

Although Evans’ reconstruction of the archaeological site is controversial, Evans’ site was indeed at the center of a civilization that held deep reverence for the bull and it is often considered to be the first European civilization period. The Minoans, named after King Minos, dominated the Aegean and Mediterranean in terms of art, economics, architecture, and religion from 3000 BCE to 1100 BCE. Of the more interesting religious aspects of Minoan civilization, and perhaps the inspiration for the Minotaur, was their practice of bull-leaping.

While it remains a mysterious practice to scholars today, Minoan bull-leaping and bulls were significant iconographies in Minoan society, as demonstrated by their brilliant artifacts, shrines, and frescos. Although the existence of Theseus and King Minos is still speculated about, there are four Minoan palaces that can still be visited today: Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros.

2. The Fall of Troy and Heinrich Schliemann

Before being written down in Homer’s Iliad between the late 8th century or early 7th century BCE, the story of Troy was already a tale at the forefront of a long oral tradition. A tale that starts at the end of a ten-year war, the Iliad recounts a crucial period of the Trojan War, a conflict between the city of Troy and its allies against a confederation of Greek cities, collectively known as the Achaeans.

The Trojan War began when Paris, the son of Troy’s King Priam, seized Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, from the Achaean king Menelaus. Prideful and bloodthirsty, a colossal army was organized for Menelaus, and they set sail for Troy, determined to reclaim Helen and become immortalized in history. Following years of warfare, pestilence, divine meddling, and Amazon intervention, the war was lost, and Troy fell despite its greatest efforts to resist the warring Achaeans.

Despite the tragic conclusion and the death of many heroes, the Iliad not only provided ancient Greeks with a sense of identity, but it also offered timeless lessons about unity, pride, grief, and rage. Although many scholars doubted the credibility of the Iliad and considered it purely fiction, there were certain individuals that believed there was some truth to the myth and it just had to be unearthed.

Following clues from the Iliad, Frank Calvert, an amateur archaeologist, arrived in Çanakkale, Turkey, and met Scottish journalist and geologist Charles Maclaren around 1847. After conferring with Maclaren, Calvert began trial excavations in 1863 at Hisarlik, a 32-meter-high mound (105 feet) suggested by Maclaren to be the site of Troy. However, Calvert’s efforts fell short due to a lack of funds.

Heinrich Schliemann, a wealthy businessman who had been invited to the site by Calvert, took the lead and began excavating in 1868. Believed to have found Troy after an array of splendid artifacts were unearthed in 1873, Schliemann made headlines and intentionally overshadowed Calvert’s initial efforts. Unfortunately, owing to the accelerated and carelessly excavated upper levels, Schliemann most certainly destroyed the very city he was looking for (Schliemann believed Troy would be in the deeper sub-levels). Instead, the artifacts unearthed by Schliemann dated to roughly 2400 BCE, more than a thousand years earlier than Homer’s Troy. Later archaeologists identified no less than nine cities that were present on the mound at one point in time and subsequently named them Troy I – IX.

Schliemann had unearthed artifacts from the Troy II sub-level, but Troy VII was the sub-level that corresponded to the Mycenaean Age and bore traces of a violent conclusion (befitting of the Iliad). It wasn’t long before Schliemann ruined much more of the archaeological site through improper excavation procedures. Despite the sure amount of duress the site of Troy had endured at the hands of Schliemann, the UNESCO site is still visible today and may have once held artifacts that could have erased all doubt concerning the legitimacy of the Iliad.

3. Medusa and the Athenian Acropolis

Before losing her head at the end of Perseus’ harpe, Medusa wasn’t always the gorgon we know. According to Ovid, a Roman poet, Medusa was a beautiful priestess of Athena who regrettably drew the attention of the lustful sea god, Poseidon. While at the Athenian Acropolis, Poseidon was said to have raped Medusa and enraged Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, for such a sacrilegious act.

Notably, Ovid’s retelling is controversial due to the fact that none of the original Greek sources mention the rape. No matter how ambiguous the interaction, Athena was enraged and sought vengeance. Targeting the defenseless maiden, Athena transformed Medusa into a creature that would turn anyone that gazed upon her into stone and turned her locks of hair into venomous snakes. Medusa fled to the island of Sarpedon and eventually became the target of countless prize hunts by renowned warriors, all of whom died horribly. You could believe Athena punished Medusa sufficiently, but you’d be incorrect. When Polydektes, king of Seriphos, gave Perseus the task of bringing him Medusa’s head, Athena was all too happy to help. Following Medusa’s beheading and the adventures of Perseus, Athena acquired the gorgon’s head and placed it on her shield or armor as an immortal emblem of her wrath.

Although Medusa was not real, the Athenian Acropolis is an actual site. The Athenian Acropolis is home to multiple monuments — the Temple of Athena Nike, Propylaea, Erechtheion, and the Parthenon. Originally used for religious dedications to Athena Polias as early as the Mycenaean Age (1600 – 1100 BCE), the plateau the Athenian Acropolis is located on has been a sacred site for over 3,600 continuous years.

During the Persian Wars in 480 BCE, King Xerxes I razed Athens to the ground, including the Old Parthenon and any other monuments that were located on the Acropolis. Furious, Cimon, an Athenian politician and commander, forbade any form of reconstruction as a reminder of the devastation caused by the invaders. Although reflective, Cimon’s discontinuance only lasted a year. Following an Athenian victory at Marathon in 479 BCE, reconstruction of the Acropolis began as part of Pericles’ master plan. The first phase of the plan was the construction of the Parthenon in 447 BCE, a project that would not be completed until 432 BCE. Although it remained unfinished, the Propylaea was constructed at the Parthenon’s entrance between 437 and 431 BCE (the Peloponnesian War halted the work and it never resumed). Following ten volatile years, the Temple of Athena Nike was finished in 421 BCE, followed by the Erechtheion in 406 BCE.

Rivaling that of the Olympic Games, every four years, the Acropolis was home to a festival known as the Great Panathenaea. During the Great Panathenaea, a procession proceeded across the city through the Panathenaic Way and concluded on the Acropolis, where a new peplos (body-length garment worn by women in Greece) was put onto the statue of Athena Polias or the statue of Athena Parthenos. Placement of the peplos was dependent on if it was the Lesser Panthenaea or the Great Panathenaea. In addition to the procession, there were athletic, musical, and rhapsodic competitions with an array of worthy prizes. Although a sacred sanctuary for the adoration of Athena, there is an ominous aspect that is hidden behind the Doric and Ionic architecture of the Acropolis. The Athenian Acropolis, adorned with gorgon antefixes, reliefs, and sculptures, also served as a reminder of the Olympian gods’ unforgiving and vengeful nature in ancient Greece.

4. The Oracle of Delphi and the Temple of Apollo in Greek Mythology

Channeling prophecies from Apollo in a phantasmagorical trance, the Pythia (or Oracle of Delphi) was one of the most powerful figures in Greece and for good reason. To receive these prophecies from Apollo, the Pythia had to perform an extensive and mystical ritual. Firstly, the Pythia bathed in Castalian Spring to purify herself, followed by the sacrifice of a goat, which her assistants would use to identify omens. The Pythia then descended beneath the Temple of Apollo into a barley and laurel leaf-fumigated chamber called an adyton.

Taking her seat upon a covered tripod cauldron at the temple center, the Omphalos, she began her transcendence by shaking bay branches and invoking Apollo. To seek the counsel of Apollo and the Pythia, one would have to bring offerings of laurel branches, money, and often sacrifice a black ram. Although there were numerous oracles across the whole of Greece, the Pythia was the most well-known and respected of them all. From key members of the city-states to kings, everyone that could afford a consultation with the Pythia had one. Among these many visitors were Lycurgus of Sparta and Solon of Athens, individuals that shaped the ancient Greek world as we know it.

Although the Pythia’s methods may sound extravagant in nature, the Pythia was a legitimate and powerful figure in Greek society. Although little is known about individual Pythias, all who served in the position were chaste females that would hold the Pythia title for the remainder of their life. Already an enigma itself (most male deities had male priests and female deities had priestesses), the Pythia was truly a fascinating figure even to the ancient world.

Given quarters within the boundaries of Delphi, Pythias were able to commit themselves to a lifetime of servitude with relative ease and luxury. Why was Delphi the location for such an important religious site? Before the erection of temples dedicated to Apollo, the site was dedicated to Gaia, the goddess of earth, mother of all life. However, Apollo would eventually steal the Pythia following his defeat of Python, protector of the Pythia and child of Gaia. Additionally, Delphi was decreed the center of the world (or the Omphalos) by Zeus and there is even an artifact that commemorates his decision at the Archaeological Museum of Delphi.

Located on Mt. Parnassus and overlooking the Valley of Phocis, the Temple of Apollo is still present. However, before reaching the Temple of Apollo, one would have to take the Sacred Way and pass the the remnants of ancient treasuries belonging to that of the Sicyonians, Thebans, Cyrenaeans, Megarians, Massaliots, Siphnians, and the Athenians, a display of just how respected the site was.