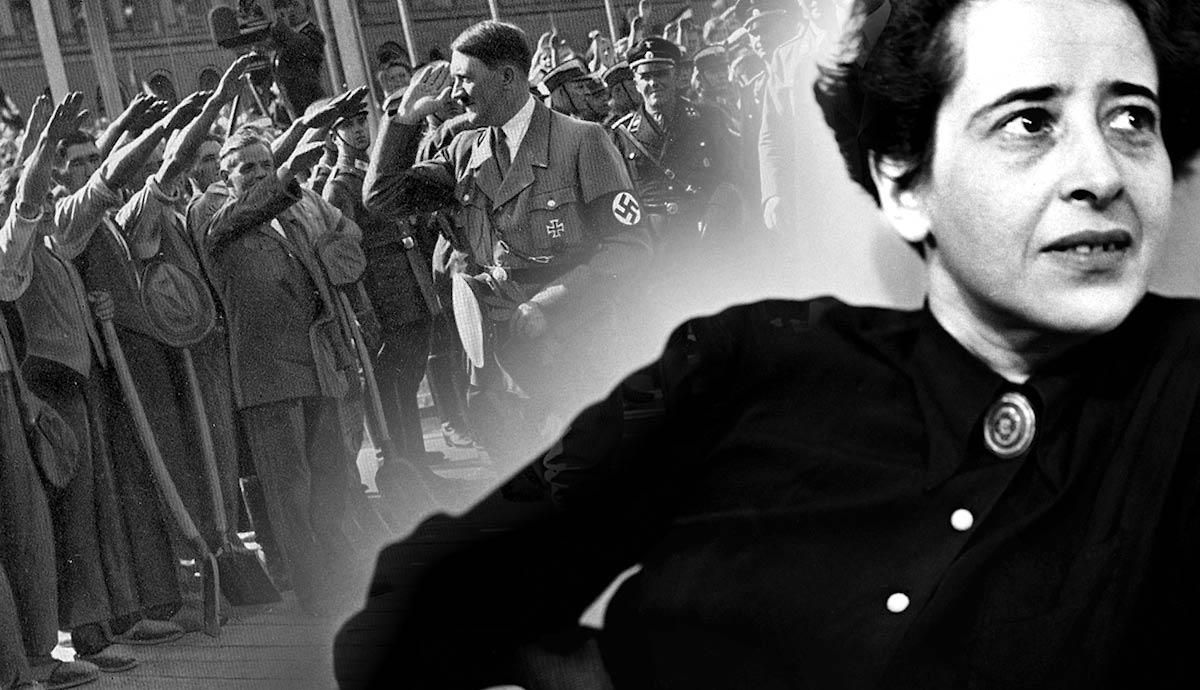

Hannah Arendt is widely regarded as one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century. Her thought was pivotal in unraveling and exploring the seemingly unexplainable horrors perpetuated by fascist regimes, which impacted her immeasurably on both a personal and academic level. For Arendt, understanding and identifying what ‘evil’ was, and how events such as The Holocaust could happen, is one of the central questions of philosophical inquiry.

Arendt and Evil: A Personal Struggle

When Hannah Arendt famously discussed the trial of Otto Adolf Eichmann, a leading Nazi officer and major organizer in the horrors of The Holocaust, her conclusion was deeply controversial. Her description of the ‘Banality of Evil’ and exploration of the role of passivity in enabling some of the greatest atrocities ever witnessed, divided and repulsed many academics attempting to comprehend the sheer brutality of what had occurred under Eichmann’s watch.

Arendt was a Jewish refugee herself, having fled the turbulence of her homeland of Germany amid growing anti-Semitism and personal betrayals. Her now high-profile relationship with her university professor Martin Heidegger, who later became a supporter of the Nazi regime, is often cited as a pivotal moment in understanding the formation of her academic and personal outlook on the rise of fascist regimes.

As a high-profile Jewish academic, coming from generations of individuals such as her mother who had to flee her homeland (now Lithuania) due to rising anti-Semitism, Arendt’s discussion of fascism became integral to her philosophy. At its heart was a desire to understand and explain evil. She explored this through a variety of lenses, relying on notions such as empire, race, and interpersonal politics to traverse and delve into the rise of totalitarian and brutal regimes.

There is a fascinating interplay of the personal and the intellectual desire for understanding within her work, a factor that could have risked clouding her vision but instead made her phenomenally gifted at exploring and deconstructing abstract concepts, and particularly ‘evil.’

The Context of Arendt’s Thought

Arendt’s writings, from the expansive The Human Condition to more focused and precise texts such as On Violence, are tied together by a central desire to understand what factors led to the events of her lifetime. There is a fundamental need expressed in these works to contextualize and unpack the nature of society in the modern day, which pushed her into exploring a vast array of topics from colonialism to populism.

A central shift in the eyes of Arendt was the rise of capitalism, and in turn a new stage in world history driven by “unlimited accumulation of power for its own sake” (Margaret Canovan, 2002, ‘The People, the Masses, and the Mobilization of Power: The Paradox of Hannah Arendt’s ‘Populism’’). As a result of this shift, the pursuit of power became prioritized over civilizational enlightenment, and human values and stability became marginalized.

This principle of expansion and devaluation of the individual became key to Arendt’s work, with her opinions on topics such as colonialism and imperialism being fundamentally rooted in this idea. For example, she believed that settler colonialism was driven by a genuine desire for the expansion of society, so viewed it as a positive force, whereas in contrast, imperialism represented the growing greed for power and marginalization of wider human interest.

When attempting to discuss and analyze Arendt’s thought, and why she was so fixated on defining and unpacking political phenomena, ideas such as her wariness of the marginalization of human interests are crucial. The complexity of these values, and the way she tackled them within her writing, make her an incredibly difficult thinker to summarize. This has led to some critics arguing that her concepts, including the ideas she had on evil, varied massively across her thought. Some critics describe Origins and Eichmann in Jerusalem as “bookends marking Arendt’s evolution of thought”, but the reality of her thought is much more nuanced and consistent than these discussions give credit (B Seyla Benhabib, 2010, ‘International law and Human Plurality in the Shadow of Totalitarianism’, p. 222).

What Did Hannah Arendt Mean by “Radical Evil”?

One of Arendt’s most pivotal and influential texts was her analysis of the rise of absolute regimes in The Origins of Totalitarianism. This work is an incredibly detailed and rich exploration of the roots of totalitarian regimes, split into three extended essays exploring antisemitism, imperialism, and finally, totalitarianism. She places certain political shifts at the center of the rise of totalitarianism, describing how, for example, “before the imperialist era, there was no such thing as world politics, and without it, the totalitarian claim to global rule would not have made sense.”

There have been criticisms of Origins as Cold War propaganda designed to demonize the Soviet Union and glorify the West. However, these discussions tend to oversimplify the nuance of Arendt’s work and the way she tackled huge and deeply controversial topics.

Centrally, Arendt’s work blames the rise of totalitarianism on a willingness, in some measure, of the people; she views it as a “product of human beings.” As she commented in her later work, On Violence, “no government exclusively based on the means of violence has ever existed”, implying some level of compliance among non-political figures.

However, it can be argued that the fundamental phenomenon that made totalitarianism so totally unique and astounding to Arendt was the way in which it reshaped humanity’s understanding of evil. This explains statements from Arendt such as “the problem of evil will be the fundamental question of post war intellectual life in Europe.” For many critics, Arendt’s obsession with tackling the nature of totalitarian regimes is accountable in part to them being, as Richard Bernstein has discussed “the closest she ever came to grasping radical evil” in how they were a “deliberate attempt to make human beings qua human superfluous.”

This concept is the crucial one to understanding both Arendt’s explanation of the nature of totalitarian regimes, as well as their truly unique horror. As she explores in her chapter on imperialism, the nature of international politics had undergone a fundamental shift in the twentieth century, and “the disintegration of the nation-state and the collapse of human rights as an effective political standard went together” (Richard J. Bernstein, 2010, ‘Are Arendt’s Reflections on Evil Still Relevant?’, p. 298). In combination with increasing antisemitism and general political turbulence, this produced a space in which totalitarianism could rise and people could be reduced to a less-than-human form.

These major societal shifts produced anxiety and fear, which were exploited by the political regime and enabled the rise of totalitarian politics. In turn, the regime creates a narrative of absolute truth, one that hinges on these anxieties and presents itself as unquestionably true. As a result, antisemitism and ideas of an all knowing leader were able to take hold over a mass of the population, and became asserted as a new truth. The result is a new stage of evil, one that to Arendt is distinctly different to previous historical events of mass murder or genocide.

Arendt’s summarisation of Evil within Origins is perhaps best captured in one of her letters to Karl Jaspers, in which she wrote how she was unable to exactly summarise “what radical evil really is… but it seems to me it is somehow to do with… making human beings as human beings superfluous.”

To Arendt, the evil of The Holocaust was not in the sheer amount of terror and violence it created but in its ability to erase the very existence of its victims, to eliminate any evidence of their lives. She spoke about how in the camps the Nazis “treat people as if they had never existed to make them disappear in the literal sense of the word.” To Arendt, this is the truest sense of evil: to not only kill such vast numbers, but to redefine truth around a political ideology and absolutely remove them in every sense of the word.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: Hannah Arendt on the Banality of Evil

Understanding the centrality of evil in Arendt’s Origins is fundamental in approaching the context of her writings on the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann was one of the central officers involved in coordinating the horrors of The Holocaust, particularly the logistics of transporting millions of Jews to their deaths in camps across Europe. Eichmann’s trial was highly publicized, and Arendt was sent to produce coverage on behalf of The New Yorker. Her reporting, and the subsequent book produced out of it, was so controversial that it still remains central to Arendt’s legacy decades on. It divided the international community, particularly among the Jewish diaspora who were reeling from the events of the previous decades.

At the core of Arendt’s analysis of the trial was her fascination with Eichmann as a person. She was shocked by how plain he was in relation to the horrors he had committed and found herself struggling to align the man in front of her with the monstrous crimes being put on trial. The coverage of other journalists, such as Moshe Pearlman, grappled with this gap too, trying to align the narrative of the horrendous evil of the Nazi regime with the seemingly ordinary individuals perpetuating it.

Here, Arendt’s understanding of fascism and its unique evil gave her a ground-breaking and insightful perspective. The issue at the heart of the rise of totalitarianism, from its construction of narratives of truth to its denial of the humanity of masses of people, was crucial to her unraveling the confusion of Eichmann. Her famous conclusion centered around her idea of the “banality of evil,” a concept that suggested that evil was not a radical force of action, but a failure to think and consider your own behaviors.

Eichmann was not a monster or a uniquely evil human being. He was instead “terribly and terrifyingly normal.” This was mirrored in Eichmann’s own discussion of his crimes, writing, “There is a need to draw a line between the leaders responsible and the people like me forced to serve as mere instruments in the hands of the leaders… I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty.” Eichmann himself echoes Arendt’s terrifying conclusion: that the horror of Eichann’s crimes was not his belief in his actions, but his terrifying lack of desire to question them.

Arendt’s works remain extensively discussed and analyzed decades after her death. In a world reeling from catastrophic events of unprecedented evil, Arendt challenged comforting narratives of good and evil and confronted the terrifying banality of the rise of fascist regimes. Understanding evil, and the conflict between the values of human progress and passive forces of political change was, to Arendt, central to our understanding of the events of the twentieth century, and crucial in humanity’s hopes to prevent such horrors from taking hold again.