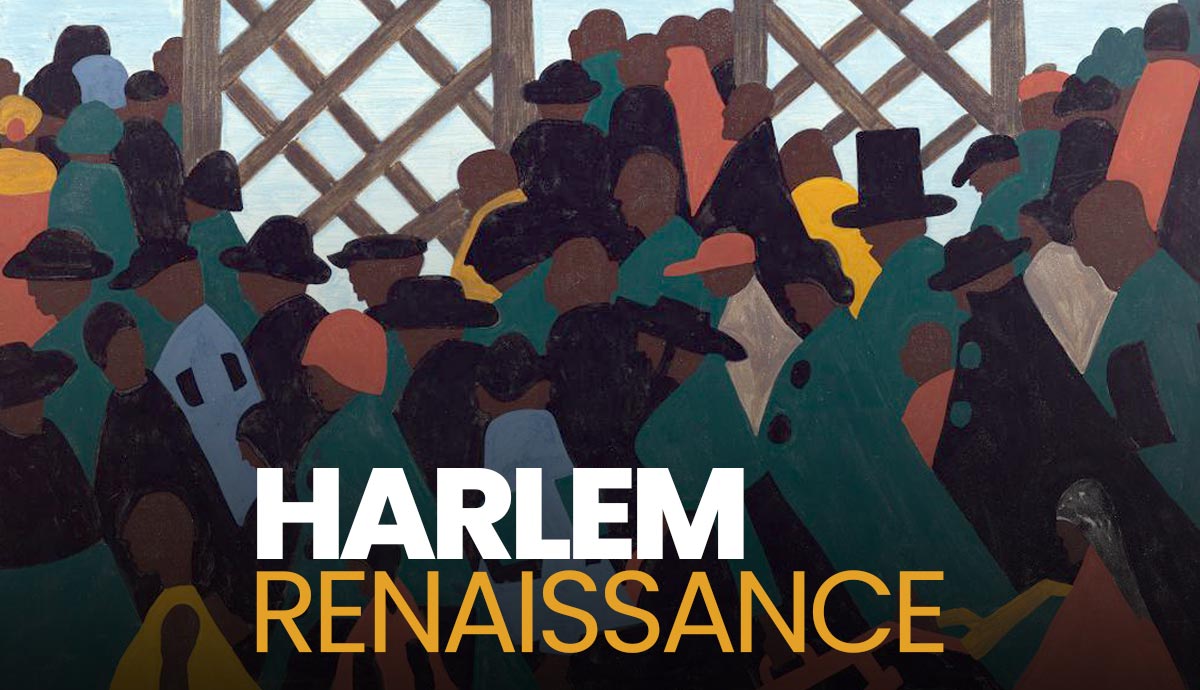

Black artists, musicians, writers, and reformers flocked to the neighborhood of Harlem in the early 20th century, creating a thriving cultural center. Their works challenged pre-existing stereotypes about Black people, chronicled everyday life, looked to the material culture and history of Africa to contextualize their own stories here in America, articulated modes of resistance against segregation and racism, and experimented with form, narrative, and theme. The legacy of their works can be seen in post-WWII arts and culture as well as in the social and political progress of marginalized groups.

What Was the Harlem Renaissance?

The Great Migration brought waves of Black people from the South to the North at the end of the 19th century through the 1920s. They were seeking jobs primarily, especially during the war years, but also sought an escape from Jim Crow and the haunting memories and legacies of slavery. Northern and Western cities such as Detroit, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, and, of course, New York City offered economic, social, political, and artistic freedom—and even if things weren’t exactly easy, it was better than the South.

Harlem was particularly appealing. Landlords had set cheap rents to entice people to the neighborhood, and industrial jobs were widely available (particularly attractive to Black soldiers returning home from WWI). Doctors, lawyers, and writers also came to the neighborhood, and others followed when they observed their success. The NAACP had formed around the same time in New York (1909) and was a powerful force for change, as was Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. James Weldon Johnson, president of the NAACP, said in 1925 that he believed “the [African American’s] advantages and opportunities are greater in Harlem than in any other place in the country, and that Harlem will become the intellectual, the cultural and the financial center for Negroes of the United States and will exert a vital influence upon all Negro peoples.”

The writer and intellectual Alain Locke described Harlem as “not merely the largest Negro community in the world but the first concentration in history of so many diverse elements of Negro life.” He put together an anthology in 1925 entitled The New Negro, which contained his essay of the same title, itself a clarion call for Black and white people to notice what was going on in Black culture.

The most notable writers to come of the Renaissance included poets Langston Hughes, Charles McKay, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Countee Cullen, and Georgia Douglas Johnson. Novelists included Zora Neale Huston, Nella Larson, Jean Toomer, and James Weldon Johnson. The categories weren’t restrictive; some poets also wrote plays, some novelists wrote essays, and some activists wrote novels.

The Renaissance faded with the crushing economic depression that began in 1929, but its influence was profound and long-lasting. Here are just a few of the ways the movement impacted life in the United States and abroad.

Challenged Stereotypes and Instilled a New Sense of Pride

The end of slavery did not mean the end of white supremacy, racism, or segregation. Prevailing racial stereotypes in the United States depicted Black people as lazy, intellectually inferior, brutish or lascivious (the former for men, the latter for women), prone to criminality, and generally unworthy of being equal members of society. The Harlem Renaissance was a powerful rebuke to those stereotypes and the negative self-image that often resulted for Black people.

This did not mean that the writers idealized things, though. Hughes said frankly in “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” younger Negro artists “who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned slaves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful, and ugly too.” Both beauty and ugliness were part of a life that could be very tough. But now, a pride in Black culture, history, identity, and selfhood was a bit more conspicuous and can be seen as a precursor to the 1960s’ oft-promulgated claim “Black is Beautiful.”

Explored Black History

Black history was not usually part of school curricula, except for brief references to Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth. Some writers began looking into the folklore, slave spirituals, and sermons of their enslaved ancestors. Others, such as Zora Neale Hurston, studied Black culture and religion in Haiti, and still others looked to Africa.

Langston Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1925), for example, placed the Black American in a larger narrative of civilization. He begins the poem by saying, “I’ve known rivers,” and then moves into a few of the most important rivers in human history—“I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were / young. / I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to / sleep. / I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids / above it.” He brings his Black ancestors to America when he adds a fourth river—“I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe / Lincoln went down to New Orleans.” Hughes made a case for Black people being at the center of the human story and those in America as the living descendants of the ancestors.

Gave Women a Louder Voice

Women writers, singers, and artists were a core part of the Renaissance. Sculptors Augusta Savage and Meta Warrick Fuller produced innovative works, and Savage taught classes at the Harlem Community Art Center, which was, the National Gallery of Art says, “critical in providing black artists continued support and training that helped sustain the next generation of artists to emerge after the war.” Mamie Smith, Bessie Smith, Gladys Bentley, and Ethel Waters crooned the blues in jazz clubs, and Alice Dunbar-Johnson held weekend salon gatherings in Washington, DC, bringing together various luminaries.

In terms of fiction, Nella Larson and Zora Neale Hurston published numerous works that explored colorism, gender, family, identity, and love. Hurston also compiled Black folklore from North Florida in Mules and Men (1935) in addition to her observations and study of Jamaican culture and Haitian vodun.

All of these women articulated what it meant to be Black and female long before the scholar Kimberle Crenshaw explicitly coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989 to describe how Black women were doubly oppressed by their gender and their race.

Gave Queerness a Louder Voice

Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote of the Renaissance that it was “surely as gay as it was Black.” Indeed, most of the main creatives were queer—Langston Hughes, Ma Rainey, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Ethel Waters, Gladys Bentley, and Richard Bruce Nugent are just a few. There were dedicated spaces to gather, cruise, and carouse, such as the Savoy Ballroom and the Hamilton Lodge, which held drag balls; the Clam House, which was a lesbian bar; Gumby’s Book Studio, a literary salon where gay men made up a majority of the attendees; and A’Lelia Walker’s lavish apartment, at which she held queer fetes.

Overall, though, the era was still one of hostility towards queerness, and queer people had to be careful. The Smithsonian notes, “Like other queer people in early twentieth century America, they were usually forced to conceal their sexualities and gender identities. Many leading figures of the period…are believed to have pursued same-sex relationships in their private lives, even as they maintained public personas that were more acceptable to mainstream audiences,” but despite the public obfuscation of their true selves, “from a modern vantage point, the work of these artists and their peers is part of the foundation of modern Black LGBTQ art.”

Fostered an International Movement

The Renaissance influenced some international movements, particularly Négritude. Négritude, which is translated as “Blackness,” was a critical and literary movement that developed in Paris in the 1930s among young people of the African diaspora. Sisters Paulette and Jane Nardal gathered Black scholars from the French colonies who’d settled in Paris and, in their salon, introduced them to Hughes and McKay. There was a sense of common ground among all these Black intellectuals, even though they had very different backgrounds.

The first writer to coin the term was Aimé Césaire in his poem “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” (“Notebook of a Return to the Native Land,” 1935). Other poets such as Leon Damas and Léopold Sédar Senghor joined with Césaire in writing works that lamented the loss of Mother Africa, called for the formation of a new identity apart from the one crafted by Europeans, and rejected European colonialism and called for independence. Césaire memorably wrote of the movement a few decades later in 1987, “Négritude, in my eyes, is not a philosophy. Négritude is not metaphysics. Négritude is not a pretentious conception of the universe. It is a way of living history within history: the history of a community whose experience appears to be … unique, with its deportation of populations, its transfer of people from one continent to another, its distant memories of old beliefs, its fragments of murdered cultures.”

The Harlem Renaissance Laid Groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement

Harlem brought together Black people from all backgrounds—academia, politics, education, art—and gave them the physical and intellectual space in which to discuss the issues of the day. Many Renaissance publications, such as Crisis, Messenger, and Opportunity, focused on issues affecting Black people, such as violence and lynchings, race riots, the detriments of discrimination, hardships for returning Black soldiers, and more. National Geographic explains that “Instead of yielding to the era’s relentless racism, the movement’s proponents openly protested it. They embraced ideals of education and progress and poured their energy into the struggle for civil rights through organizations like the NAACP, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, and African Communities League. These institutions encouraged Black Americans to agitate for social change and civil rights…”