Henri Cartier-Bresson was one of the most important and influential photographers in the history of art. Cartier-Bresson’s works present an intersection of artistic skill and journalistic documentation. His works reflect on the most tragic and significant moments of the twentieth century. The artist’s photographs can also help us learn more about the recent past. Here are 7 iconic images made by the great Henri Cartier-Bresson that you need to see!

1. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Gestapo Informer Recognized by a Woman…

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a true legend of photography, in both artistic and documentary sense. Unlike many of his colleagues, he never faked his images but simply observed things happening without intervening. His work during and after World War II was far from simply being impartial documentation of war crimes. It also functions as a deep study of characters and traumas. Cartier-Bresson’s main instrument was his artistic gaze. He wrote that good photographers had to train themselves to look all the time, even unconsciously.

One of the most famous images of World War II was captured by Cartier-Bresson in 1945 in Dessau, Germany. In a crowd of displaced persons waiting for repatriation, a woman recognizes a Gestapo informer. The collaborator tried to hide in the crowd but was noticed and brought forward. Originally, this scene was captured as a part of Cartier-Bresson’s film Le Retour, a documentary of the repatriation of French war prisoners. The photographer himself spent three years in a German work camp, escaping in 1944 and joining the French underground forces. However, the scene of the collaborator’s exposure was removed from the film and remained only in Cartier-Bresson’s photographs.

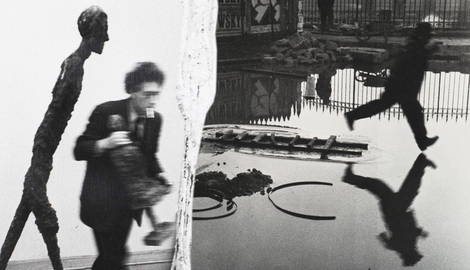

2. Alberto Giacometti, Maeght Gallery, Paris

Visual rhythms were essential for Cartier-Bresson’s work, yet he never staged them or specifically searched for them. Reality arranged itself without external interventions. You just had to know how to wait and how to look. In his worldview, every shape, every line, and every figure participated and depended on one another. The photograph of Alberto Giacometti, pacing frantically between his sculptures is both a portrait of the great sculptor and an ironic sketch. Somehow, the master turned into one of his own works, immersing and dissolving in his creations. Cartier-Bresson’s approach to portrait photography is evident in this image. The photographer wrote about having to put the camera between the skin of a person and his shirt.

Alberto Giacometti and Henri Cartier-Bresson became friends in the 1930s. During this time, both artists were enthralled by Surrealism. Despite working with different techniques, they shared a common approach to observing reality. They even liked the same artists like Paul Cezanne, Paolo Uccello, and Jan van Eyck. Cartier-Bresson once said that Giacometti’s intellect was an instrument in service of his sensibility. Perhaps, this could be applied to both of them.

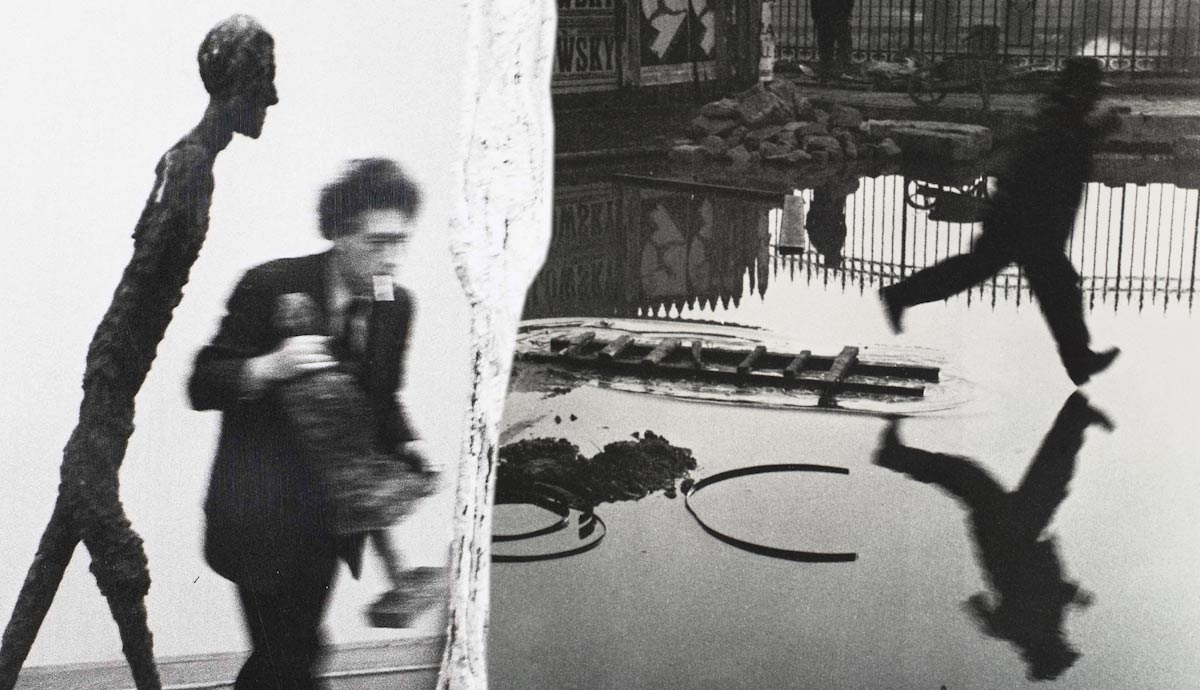

3. Behind the Gare St Lazare

For Henri Cartier-Bresson, the main component of his work was the so-called decisive moment, a second when all elements of reality align perfectly. The photographer’s goal was to notice that moment and capture it. The legendary photograph Behind the Gare St Lazare illustrated this principle perfectly. Cartier-Bresson managed to take a photo right when an unknown passerby was leaping over a puddle. Curiously, with his attentive outlook on the world, the photographer was indifferent to developing images. The technical side of the process, the magic that keeps fascinating photographers even today, was of no interest to him. His involvement as a creator started and ended with the shutter of a camera lens, capturing a single moment of fleeting and unstable reality.

In fact, Gare Saint-Lazare, one of the main train stations in Paris, attracted the attention of many artists long before Cartier-Bresson’s created his image. Located in one of the central areas of the city, it can be found in the paintings of Claude Monet, Edouard Manet, Gustave Caillebotte, and other artists of their generation.

4. Henri Matisse at his home, Vence

Henri Cartier-Bresson started his training as a visual artist taught by a Cubist Andre Lhoté. Lhoté was a friend of many avant-garde artists, yet his Cubist works had a much softer style, with bold colors and recognizable scenes from reality. Cartier-Bresson did not stay a painter for too long, finding his ideal medium in photography. Still, he kept practicing visual arts to develop his skills as a photographer. One of his main instruments to develop his unique artistic perspective was automatic drawing. Created with as little control as possible, it helped Cartier-Bresson find the balance between the conscious and the subconscious.

Nonetheless, despite his departure to the domain of photography, Cartier-Bresson never left the art world completely. He captured many famous artists in their natural environments. One of them was Henri Matisse. They met in 1944, soon after Cartier-Bresson escaped from the Nazi work camp. While still hiding from the Germans, Cartier-Bresson kept working on documenting the reality of occupied France. Matisse was not feeling well at the time, unable to walk after his cancer surgery, he was working on creating collages from paper cut-outs. Cartier-Bresson visited him frequently, observing the artist at work.

5. Martine Franck

Many of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s works present unusual angles and compositions, with some elements reaching beyond the borders of the picture plane. However, Carrier-Bresson never did this after the photograph was taken. He refused to edit or crop his images, insisting that his original vision did not need extra involvement. For Cartier-Bresson, photography was simultaneously the question and the answer, present in the camera’s viewfinder. Still, he insisted that the camera should be an extension of a photographer’s eye, hand, and senses.

Martine Franck was a Belgian photographer, a member of the Magnum Photos cooperative, and the second wife of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Unlike many of her other colleagues from Magnum, Franck avoided working on war photography. Instead, she focused on capturing the daily lives of women, children, and the elderly. Her works were full of love and sheer curiosity about the world and its inhabitants.

Unfortunately, the great shadow of her husband concealed a large part of Franck’s achievements. In 1970, she canceled her first-ever solo exhibition in London, after learning that the invitations advertised a meeting with Henri Cartier-Bresson, and not the artist being represented. Still, after Cartier-Bresson died in 2004, Martine Franck became the president of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, preserving the work of the legendary photographer and promoting other gifted artists.

6. Seville, Spain

Henri Cartier-Bresson captured the turbulent climate of the 1930s in Spain in great detail, covering both violent conflicts and everyday life. This was an early period of Cartier-Bresson’s photographic work, and some experts notice the influence of his Cubist training in his compositions. Numerous figures present in the images were aligned with great precision. At the time, Henri Cartier-Bresson was only at the beginning of his path as a photographer, yet the carefully arranged details, including the interplay of human figures and buildings around them, already illustrated his skill and expertise.

During his visit to Seville in 1933, Cartier-Bresson noticed a group of children playing in the remains of a building, unaware of the photographer’s presence. Normally, ruins of destroyed houses are not happy places, but these children were not concerned with this. The loud and joyful game amidst these ruins could be seen as a promise of a new and better future. However, the Spanish Civil War would unfold just three years later.

7. Roman Amphitheater, Valencia, Spain by Henri Cartier Bresson

One of the most famous images made by Henri Cartier Bresson presents us with a complex composition of elements in need of explanation. Taken from the amphitheater ring used for bullfighting, the photograph focused on a rectangular structure of a wooden door through which the bull entered the arena. One guard is seen watching the performance through a small opening, while the other, a blurred figure in the background, is closing one of the doors behind. To capture this scene, Cartier-Bresson had to enter the arena during a fight.

The Spanish government several times attempted to ban bullfighting or at least prohibit killing bulls during fights, yet every proposal was met with a backlash from conservative politicians and citizens. Despite its cruelty, bullfighting remains an important part of Spanish cultural heritage, with its origins traced back to prehistoric times. In the 1930s, when Cartier-Bresson captured this image, bullfighting was considered a symbol of masculinity and fearlessness. Still, even in the early twentieth century, some activists were protesting the tradition, claiming it held Spain back from social and economic development.