The two grand masters of modern art shared a lifelong bond. They shared friendship, but there was also rivalry. Matisse compared their relationship to a boxing match, while Picasso admitted that if he were not Picasso himself, he would have painted like Matisse. Here are six facts about the relationship between the two great artists that you should definitely know.

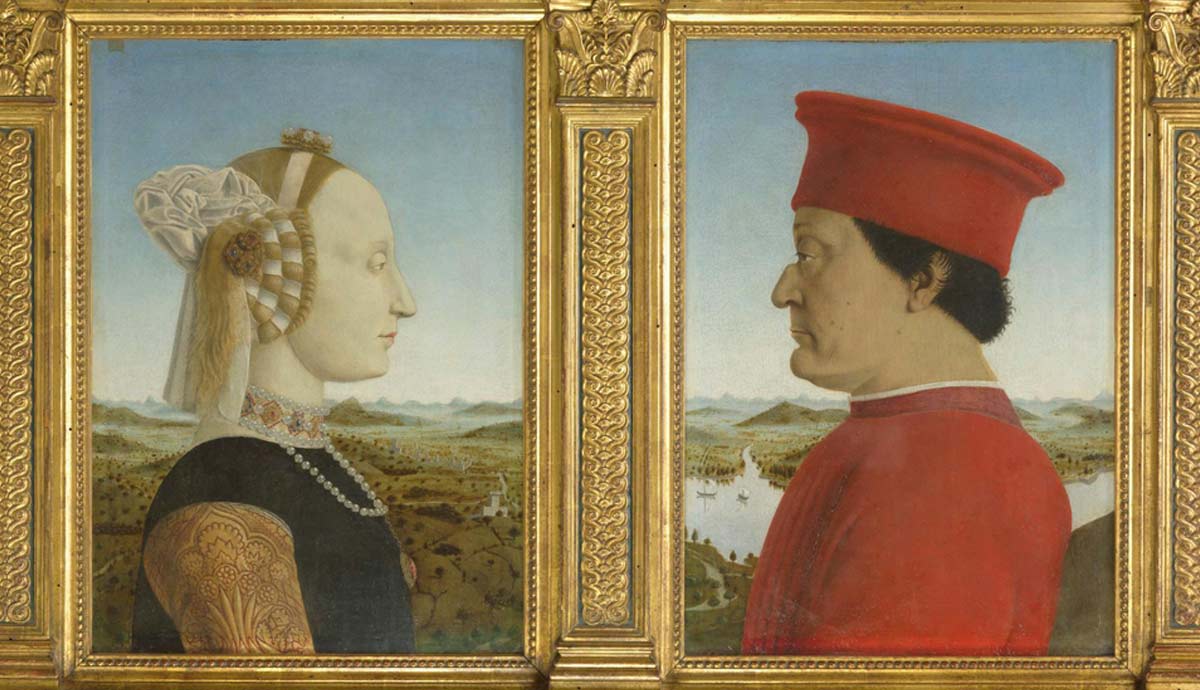

1. Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso Came from Different Backgrounds

Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were main characters in the history of modern Western art. For several decades they shared a bond and a remarkable friendship that sometimes seemed like a mutual hatred. They were polar opposites in everything, from artistic styles to personalities, but they appreciated each other’s innovations.

Henri Matisse, a promising lawyer turned painter, had methodic training in the most progressive art institutions of his life. Picasso, on the contrary, was a child prodigy, a young radical aimed at dismantling all things conventional. Matisse once said that he strived to create art as comforting as a good armchair, and for that quote, Picasso mocked him for years.

They met around 1906 during a group exhibition. Unexpectedly, the bond between the two artists grew quickly, fuelled by mutual curiosity and respect for their artistic experiments. Despite their differences, they shared artistic influences. Picasso and Matisse found massive inspiration in the works of Paul Cezanne and Non-Western art, which was being introduced to the Western public at the time.

Matisse’s trips to Morocco and Tahiti left a lasting trace in his work, with dozens of Orientalist paintings of odalisques, decorated interiors, and landscapes. Picasso, on the contrary, did not need to travel to add new motifs to his work. His main explorations happened inside his head and in art galleries. Picasso was one of the first artists who appreciated African art. He had his own collection of African masks and statues. The influence of these masks is clearly visible in his early Cubist works.

2. Picasso and Matisse Relied on the Same Patron

Contemporaries were rarely kind to the leading avant-gardists. Yet, Europe had several visionary collectors who were ahead of their time. These people financially supported the most progressive artists of their time. One of these visionaries was a Russian textile manufacturer called Sergei Shchukin. The Shchukin family was well-known for their vast collection of art, but Sergei was the most progressive of them all, always keeping track of the latest trends in French painting.

Shchukin was passionate and sometimes irrational about his collection. While most art collectors had a sensible approach, choosing one specific niche and picking the best pieces available in the market, Sergei Shchukin fell in love with almost everything, spending enormous sums on works that seemed ridiculous to both the French and Russian audiences. He was interested in everything, from the Impressionists to African sculpture. Picasso’s work was one of his major obsessions. This resulted in fifty paintings that are now owned by major Russian museums.

Henri Matisse was another favorite of Shchukin. He has 38 paintings made by Matisse in his collection. Matisse even came to Moscow to supervise the installation of his works in Shchukin’s house. One of the most famous works by Matisse, the legendary blue-and-red Dance almost made the artist and his loyal patron part ways. Shchukin commissioned it as a decorative piece for the main stairway in his Moscow mansion. Matisse’s idea was that the painting, with its bright colors and dynamic lines, would help the visitor ascend.

Originally, Shchukin was happy with it, but after the first public presentation in Paris which resulted in public outrage, he changed his mind and refused to buy the painting. Matisse was desperate, but his frustration did not last long. A few days later, Shchukin sent him a note written on the train from Paris to Moscow, apologizing for his moment of weakness and asking Matisse to send him the painting.

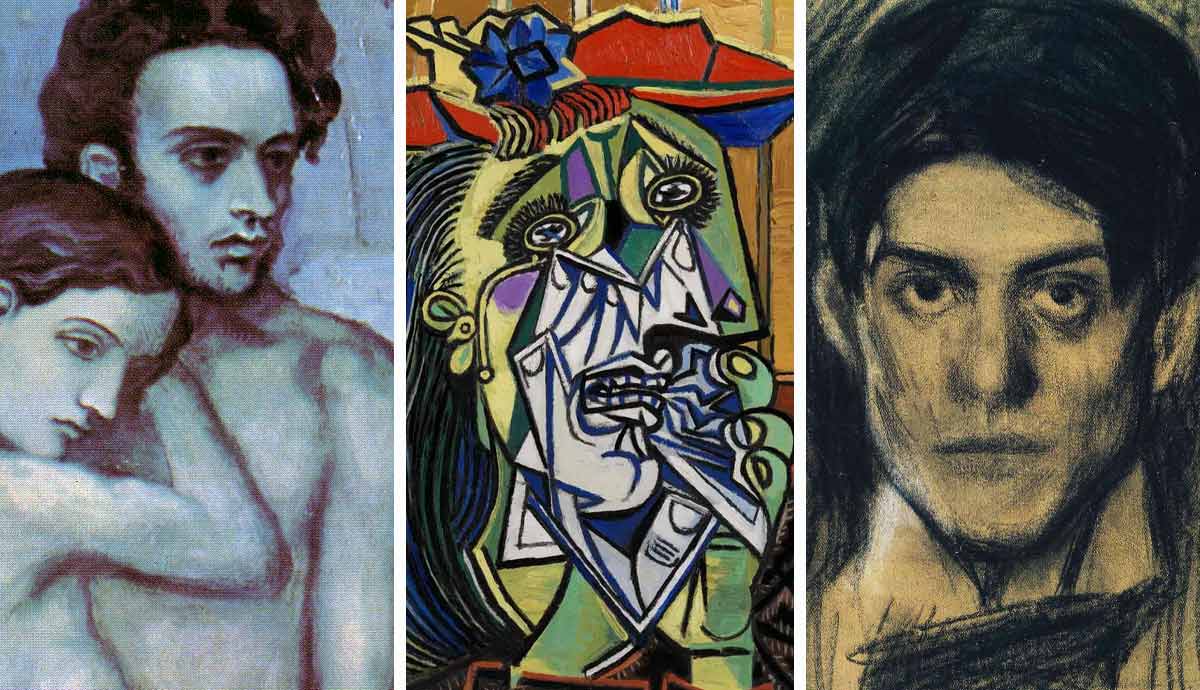

3. They Exchanged Ridiculous Gifts & Tried to Steal Each Other’s Paintings

Despite their mutual respect, Matisse and Picasso often behaved like they were testing each other’s patience. Exchanging gifts was one of the ways to annoy one’s opponent but also an attempt to lead them to a new discovery. Picasso once gave a broken piece of painted ceramic Matisse without an explanation. Matisse responded in a similar fashion. He offered a ridiculous statue of a Polynesian idol to Picasso during one of his friendly visits. Confused, Picasso conveniently forgot about the sculpture at Matisse’s house and then complained to his partner Francoise Gilot that it was the ugliest thing he had ever seen.

Still, these ridiculous acts were far from simple insensible jokes. Both Matisse and Picasso understood well that their rival never did anything for no good reason. Picasso spent hours and hours in art galleries next to Matisse’s paintings, trying to understand his methods and reasons. Matisse was less polite about learning his friend’s secrets. Once, he almost stole Picasso’s landscape.

In his later years, bedridden Matisse was fascinated by Picasso’s painting Winter Landscape. He asked the artist to borrow the painting for a few days to closely inspect it. He later refused to return it, making excuses that he wasn’t done with analyzing it. Matisse even found a permanent place for the work on his bedroom wall.

4. Matisse Decorated a Church… and Picasso Wasn’t Happy About It

One of the most famous works by Henri Matisse is not a painting or a colorful collage but the interior of The Rosary Chapel in Vence on the French Riviera. This unusual project found him through his former nurse Monique Bourgeois, who joined a Dominican convent. It was Bourgeois who offered Matisse to decorate the new chapel built for the girls’ school operated by the convent. Although Matisse was not a practicing Catholic, he was happy to help. The small L-shaped chapel was filled with stained-glass windows decorated with abstract ornaments and mosaic murals.

Picasso, a radical atheist and a member of the Communist Party was outraged by that decision. He claimed that Matisse, as a non-believer, should not have agreed to do the project. In turn, Picasso designed a market meant to be used by all citizens.

However, this criticism did not stop Picasso from designing his own chapel in Vallauris in southeastern France. His mural War and Piece was one of the largest works ever created by Picasso. Trying to avoid accusing Picasso of hypocrisy, many art experts state the artist decided to focus on universal subjects of war and peace instead of focusing on Christian topics.

5. Both Matisse and Picasso Worked for the Ballets Russes

Nearly every major artist was somehow involved in the productions of Ballets Russes, a traveling dancing company led by Sergei Diaghilev. Picasso and Matisse were no exception, but their involvement had entirely different outcomes. Picasso started working with Diaghilev first, as early as 1917. Their first collaboration was the design for the one-act ballet Parade, written by Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. Parade was a short story about circus performers trying to attract the audience’s attention. Costume design expressed Picasso’s signature cubist contours of streets and acrobat tricots found in his Rose period. During the next seven years, he would create designs for six other productions, including Le Tricorne which was inspired by Spanish culture. Picasso also found a new muse here, the ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova whom he married in 1918.

Unlike Picasso, Matisse enjoyed little success working with Diaghilev. His attempt to design costumes for the ballet Song of the Nightingale turned into a disaster. For the dancers, he created floor-length robes decorated with embroidery and collaged pieces of fabric. The only thing Matisse forgot to consider was body movement. His designs were stunning when immobile but turned into a chaotic mess when in action. Desperate, Matisse asked the lead choreographer Leonide Massine to make the main character of the ballet static. The public did not react to this well, so the Song of the Nightingale became one of the least successful Ballets Russes productions.

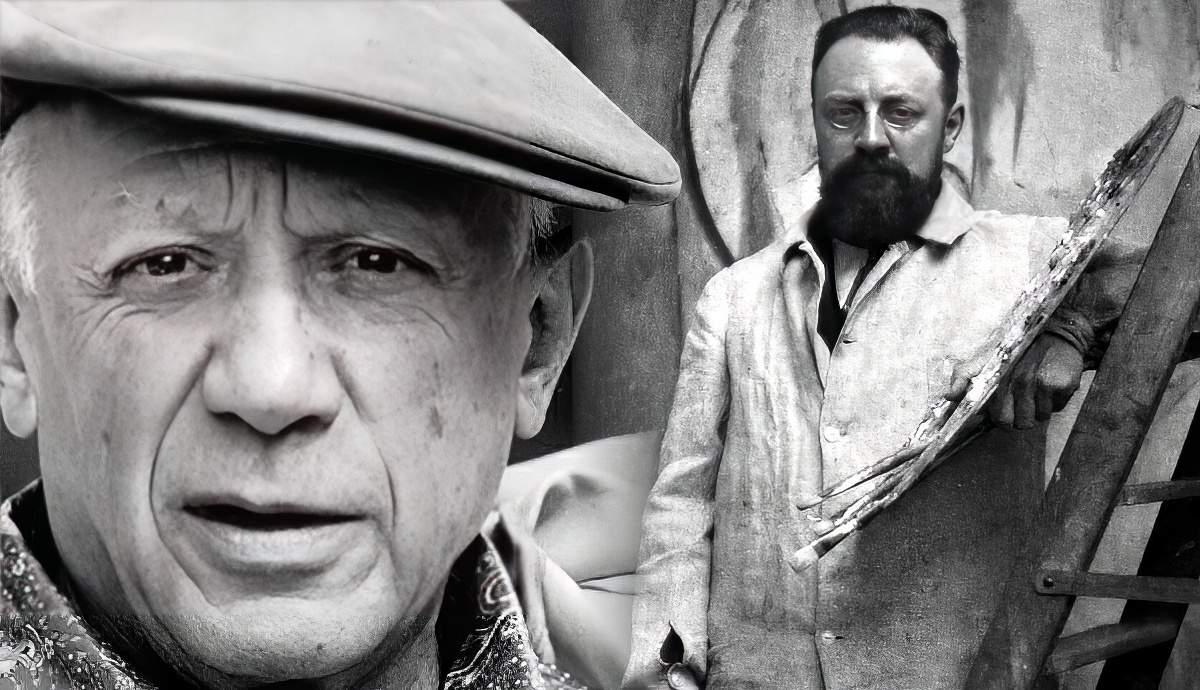

6. Picasso Ignored Henri Matisse’s Funeral

In his late years, bedridden Matisse often complained that Picasso did not visit him often enough. The artist noted that should one of them die, the other would have no one to talk to for the rest of his life. Paloma and Claude Picasso, the artist’s youngest children, remembered every visit to Matisse’s house as something filled with laughter and many conversations. Matisse passed away in November 1954. His daughter phoned Picasso immediately, but he never picked up or returned the call. Picasso never came to the funeral. Some people saw this as disrespect.

For some, it seemed that Picasso could not accept that his rival was no longer alive and deliberately ignored the evidence of that. His way of coping was art. In the years following Matisse’s death, Picasso painted fourteen paintings of Algerian women, or at least his idea of Algerian women. He told his friends that Matisse left him his odalisques as a legacy to develop further. The series was not only a nod to Matisse’s art but to the favorite painting of both artists, Eugene Delacroix‘s Women of Algiers. Picasso’s grief and loneliness found their expression in an imaginary collaboration, which never happened during Matisse’s life.