King Eurystheus ordered Heracles to capture the Cretan Bull and bring it to him as part of his seventh labor. Prince Minos sought a sign from Poseidon to confirm his right to rule Crete. Poseidon sent a magnificent bull, and Minos became the king. However, Minos did not show gratitude to Poseidon by sacrificing the bull. As punishment for Minos’s disrespect, Poseidon cursed Queen Pasiphae with unnatural lust and unleashed the bull to wreak havoc across Crete. Read more about the Cretan bull and its epic encounter with the mighty Heracles.

The Cost-Benefit of Commanding a Hero

Heracles‘s reputation within Eurystheus’s Kingdom was increasing. His fame skyrocketed after he successfully eliminated the army of Stymphalian birds from the swampy shores of Lake Stymphalia in the northeastern Peloponnese. Heracles had consistently proven himself, solidifying his status as a true hero across the Peloponnese peninsula. This feat represented the halfway point of his twelve labors and the beginning of the non-Peloponnesian labors of Heracles. During this time, the hero journeyed to various locations across the Mediterranean to complete his labors.

Heracles’s increasing fame and recognition became a constant concern for King Eurystheus. The goddess Hera tasked the King with both humbling and punishing Heracles for his crime of blood murder. However, with each difficult challenge Eurystheus set, Heracles emerged triumphant, further boosting his fame. The hero’s growing notoriety, as he eliminated every threat to the livelihoods of Eurystheus’s subjects and the broader Peloponnese population, presented a silver lining to the King.

Heracles’s labors carried out under Eurystheus’s command, had significant political implications. In a previous task, Eurystheus had sent Heracles to deal with King Augeas’s stables. This action showed Eurystheus’s ability to use Heracles’s hero status to strengthen his political connections with other Greek leaders. Heracles’s rising political influence and popularity were crucial in shaping his next challenge.

For his seventh labor, Eurystheus ordered Heracles to capture and deliver to him the Cretan Bull. The distant isle of Crete, the birthplace of Zeus and, according to some, the birthplace of Greek civilization, was considered a legendary and mythical land even during Heracles’s time. Under King Minos’s rule, Crete was a political powerhouse. Minos’s father, Zeus, guided the King’s rule and helped the King create the first known constitution and legal system. Under Minos, the Cretan army and navy flourished, and from his throne in Knossos, one of the oldest known Greek cities, Minos controlled most of the islands of the Aegean Sea. Recognizing this, Eurystheus made a strategic move. He sent Heracles to deal with the Cretan Bull, not just as another trial for the hero but as a means to secure political favors from the most powerful King in Greece and strengthen his rule on the Greek mainland.

The Tale of the Cretan Bull: The Sacrifice

The Cretan Bull is a significant figure in several Greek myths. Its encounter with Heracles is part of its long and storied history. The tale of the Cretan bull is closely associated with Minos, the King of Crete. Bulls play a recurring role in Minos’s life. Minos, the son of Zeus and Europa, was born after Zeus, in the form of a white bull, abducted Europa, the sister of the hero Cadmus, and took her to Crete. There, they had three sons: Minos, Sarpedon, and Rhadamanthys.

In a manner befitting Zeus, the King of the Olympians quickly abandoned Europa on Crete after their affair. However, he did not leave before giving her necklaces crafted by Hephaestus and three additional gifts to soften his desertion. The first gift was Talos, a giant bronze automaton made by Hephaestus to protect her. The second was a dog named Laelaps, who never failed to catch his prey, and the last was an enchanted javelin that never missed its mark.

Europa, now a mother of three infant sons, was not deserted for long. Her beauty, wit, and impressive collection of magical gifts made her the ideal bride for Asterion, the King of Crete. The two were soon married, and Asterion adopted Europa’s sons, raising them as his own and using his new wife’s gifts to strengthen his Kingdom. For generations, the bronze automaton Talos became the legendary protector of the island’s borders.

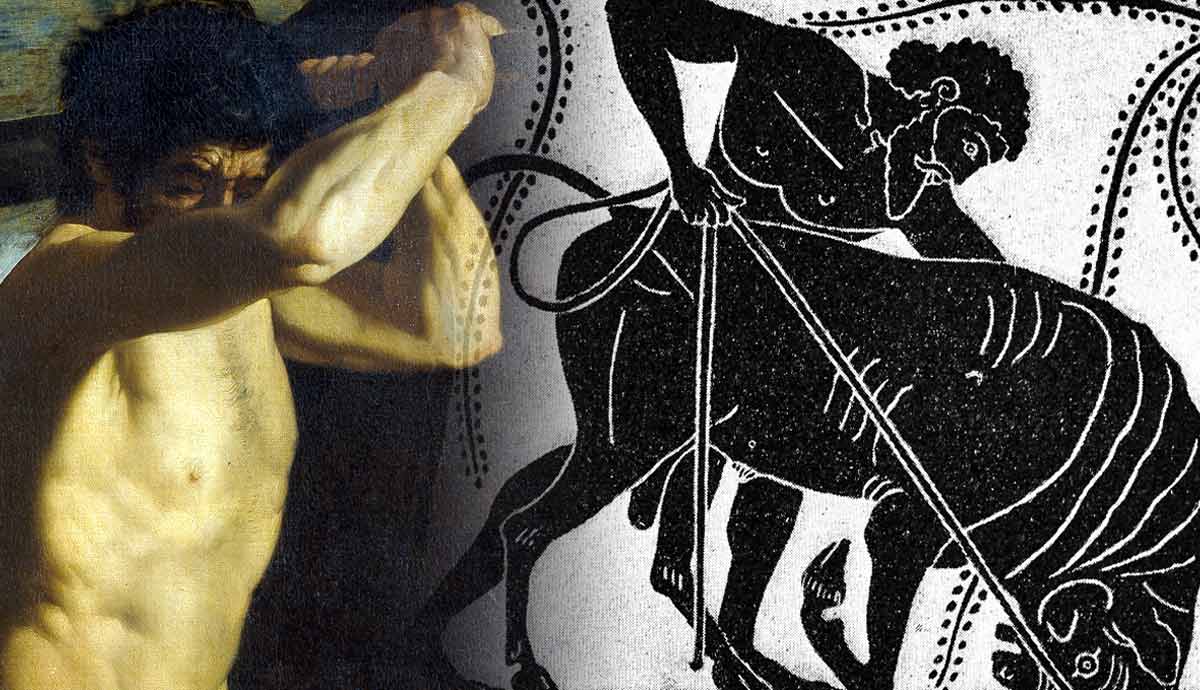

After Asterion died, his three adoptive sons began arguing over who should become the next King. While Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys bickered, Prince Minos prayed to Poseidon for help. He asked Poseidon to send a clear sign proving he was the rightful successor to the Cretan throne. In return, Minos promised to sacrifice whatever Poseidon sent as a sign of gratitude. Poseidon answered Minos’s plea by sending a magnificent snow-white bull from the ocean to Crete. The appearance of the majestic animal was interpreted as a divine sign that Minos should become the island’s next ruler.

As promised, Poseidon expected King Minos to sacrifice the beautiful bull in his honor. But Minos could not bring himself to sacrifice such a handsome ox. Instead, he sent the beautiful bovine to live among his herd and sacrificed an inferior bull in its place. Minos’s deception and insult did not go unnoticed by Poseidon, who devised a two-stage punishment for the King who dared to trick an Olympian.

The Tale of the Cretan Bull: The Curse

Poseidon’s anger toward mortals often resulted in earthquakes, tidal waves, or fierce sea storms. However, the lord of the sea used a different method to enact his revenge upon Minos. For the first part of his plan, Poseidon asked for the help of his fellow Olympian, Aphrodite, the goddess of love and lust. It takes a particular type of courage or stupidity to defy the Olympians; in Minos’s case, it was a courageous stupidity fueled by his love and obsession with the beautiful Cretan bull.

Poseidon asked Aphrodite to transfer Minos’s passion for the bull to his wife, Queen Pasiphae. Pasiphae, the daughter of the sun god Helios and sister of the famed enchantress Circe, was herself an eminent sorceress. Nevertheless, her abilities could not protect her from Aphrodite’s magic. The curse resulted in Pasiphae lusting over the Cretan bull and feeling compelled to somehow make love to him.

To fulfill her unnatural desire, Pasiphae sought the assistance of the legendary inventor Daedalus to devise a method for her to mate with the bull. Daedalus constructed a mobile, hollow cow that, at first glance, appeared to be genuine. In the hollow cow, Daedalus created a hiding place for the queen. If everything went as planned, this spot would allow her to fulfill her desires. Daedalus’s invention succeeded, and under Aphrodite’s influence, Queen Pasiphae mated with the Cretan Bull. As a result, Pasiphae became pregnant and gave birth to a half-human, half-bull son named Asterion, after his adoptive grandfather. This child would become better known to the world by another name: the Minotaur.

After the bull mated with the Queen, Poseidon lifted the curse on Pasiphae and sent the bull mad, unleashing devastation across the island. While Minos was handling a scandal at home, reports poured in from all over the island, detailing the chaos and loss of life brought about by the rampaging snow-white bull. King Minos was relieved when King Eurystheus offered to send Heracles to confront the Cretan Bull, allowing Minos and the inventor Daedalus to devise a plan to address the shame and embarrassment brought about by the bull’s offspring.

Heracles and the Bull

When Heracles arrived on the shores of Crete, Daedalus was likely hard at work constructing the legendary labyrinth to hide the Minotaur. By the time Heracles got there, the unstoppable bull had been causing havoc for months, resulting in unimaginable damage. It had killed hundreds of people, destroyed local infrastructure, and devastated crops across the island’s countryside. The wild animal proved too deadly for the King’s brave hunters to subdue it. However, stopping an angry bull was simple for Heracles, a man who had defeated the undefeatable and caught the uncatchable.

The influence of the Cretan Bull on Greek myth is arguably more profound than that of any other creature Heracles encountered in his labors. Despite being sent by Poseidon, the bull’s sole supernatural attribute was its breathtaking beauty. It did not possess an impenetrable hide, immortality, or supernatural strength and speed. It was simply a creature of untamed fury. After a brief encounter with Minos, Heracles quickly tracked down the bull, guided by the wake of the devastation it left behind.

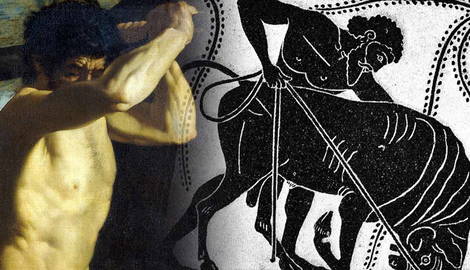

Once Heracles spotted the bull, he swiftly put his plan into action. Heracles began yelling and hurling rocks at the furious animal. The enraged bull turned and charged straight at Heracles as he had anticipated. As the bull thundered toward him, Heracles positioned himself and sprinted headlong toward the oncoming beast. Heracles’s task was to capture the bull and bring it back to Eurystheus unharmed, and he had devised a simple yet ingenious strategy: when the bull charged, he would confront it and take the bull by the horns.

The sight of Heracles fearlessly rushing toward an angry bull must have left any spectators in awe. The impact of the colossal hero and the bull when they collided would have echoed across the island. Having already subdued formidable creatures like the Nemean Lion and the swift Ceryneian Hind, overcoming and capturing the Cretan Bull seemed comparably effortless for Heracles.

Heracles wrestled the Cretan Bull into submission using only his strength and bare hands. It took several hours to gradually drain the furious bull of its strength, but Heracles eventually managed to bend the fatigued bull to his will. After successfully capturing the bull, Heracles left the island of Crete with only the briefest show of gratitude from Minos, as the royal palace still had other secrets it was preoccupied with. According to some versions of the myth, Heracles mounted the bull and rode it across the Mediterranean Sea back to Eurystheus in Tiryns. Others claim that Heracles restrained the animal and sailed back by ship.

The Aftermath

When Heracles arrived outside the city gates of Tiryns, the Cretan Bull terrified King Eurystheus. The King might have leaped back into his large jar if it were not for the joy he now felt. Perhaps the King was pleased to see the hero for the first time in Eurystheus’s relationship with Heracles. Minos, the ruler of one of the most powerful Kingdoms of its time, now owed Eurystheus a favor thanks to Heracles’s work.

The greater political implications of the bull’s capture went over Heracles’ head. All the hero was concerned about was what he was supposed to do with the ox and what his next labor was. Eurystheus planned to sacrifice the bull as the gods had initially intended. The King decided to sacrifice the bull to honor Hera instead of Poseidon. However, before the sacrifices could begin, Hera told Eurystheus that she would not accept it due to Heracles’s involvement. The Queen of Olympus refused to accept any sacrifice, recognizing her nemesis’s victories.

Unable to sacrifice the bull, Eurystheus commanded Heracles to release it outside the city gates. The newly freed bull then traveled out of the Peloponnese peninsula and into the eastern region of Attica, where it finally settled near Marathon. There, the Cretan Bull continued its rampage, causing death and devastation to the local populace. It would, after that, be known as the Marathonian Bull.

The Marathonian Bull would later become a problem for the nearby city of Athens. To solve the issue, the Athenian King Aegeus sent Androgeus, a renowned athlete and the son of King Minos, to kill the beast. Tragically, the bull killed Androgeus. When Minos learned of his son’s death, he blamed the entire city of Athens and declared war on them. Due to their superior navy, Crete defeated Athens and imposed a treaty demanding that Athens send 14 youths to the island every year or every seven or nine years, depending on the version. These youths were then sacrificed to the Minotaur, bringing the influence of the Cretan bull full circle. Eventually, the bull was captured and sacrificed by the hero Theseus. This cunning hero would later navigate the infamous labyrinth, slay the Minotaur, end Cretan dominance, and lead Athens to prominence.

As Heracles gazed at the snow-white ox vanishing over the Peloponnese horizon, the legendary life of the bull and its inevitable encounter with Theseus were still unwoven threads held by the sisters of fate. With the bull now out of sight and out of mind, Heracles turned to Eurystheus to await instructions for his eighth labor: Stealing the Mares of Diomedes.