The effort of South Africa in World War II is often associated with the actions of the British colonies, dominions, and protectorates, and it is often overshadowed by the exploits of Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and even India (whose contribution was staggering compared with the recognition it gets).

Nevertheless, South Africa provided invaluable assistance to the war effort that should not be forgotten. In its own right, South Africa’s World War II story is an interesting one, worthy of great renown.

Entry Into World War II

South Africa’s entry into World War II was a complex matter which divided the country along ideological lines. As a result of the 2nd Anglo-Boer War, there was a deep schism between the English and Afrikaans speakers in South Africa, and it was these two groups that held all the authoritative power. Less than four decades before World War II, Afrikaners had been subjected to genocide at the hands of the British. Thus, many Afrikaners held a deep animosity towards anything pro-British.

South Africa was a dominion of the British Empire, and thus it had close ties with Britain. However, the Prime Minister of South Africa, JBM Hertzog, who, as the head of the pro-Afrikaner and anti-British National Party (the same entity that would go on to establish apartheid), wanted to keep South Africa neutral. The National Party ruled in a government of unity with the South African Party, and together they represented the United Party.

On September 1, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain declared war on Germany. This precipitated a fierce debate in the South African parliament. It pitted those who wished to remain neutral, led by JBM Hertzog, against those who wished to enter the war on the side of the United Kingdom, led by General Jan Smuts. Ultimately, the pro-war vote won out, and Smuts replaced Hertzog as leader of the United Party. Hertzog was forced to resign, whereupon Smuts took up the mantle of Prime Minister and led South Africa into war against the Axis. As with every country that took part, World War II would test South Africa’s resolve, and not just on the battlefield.

The African Theaters

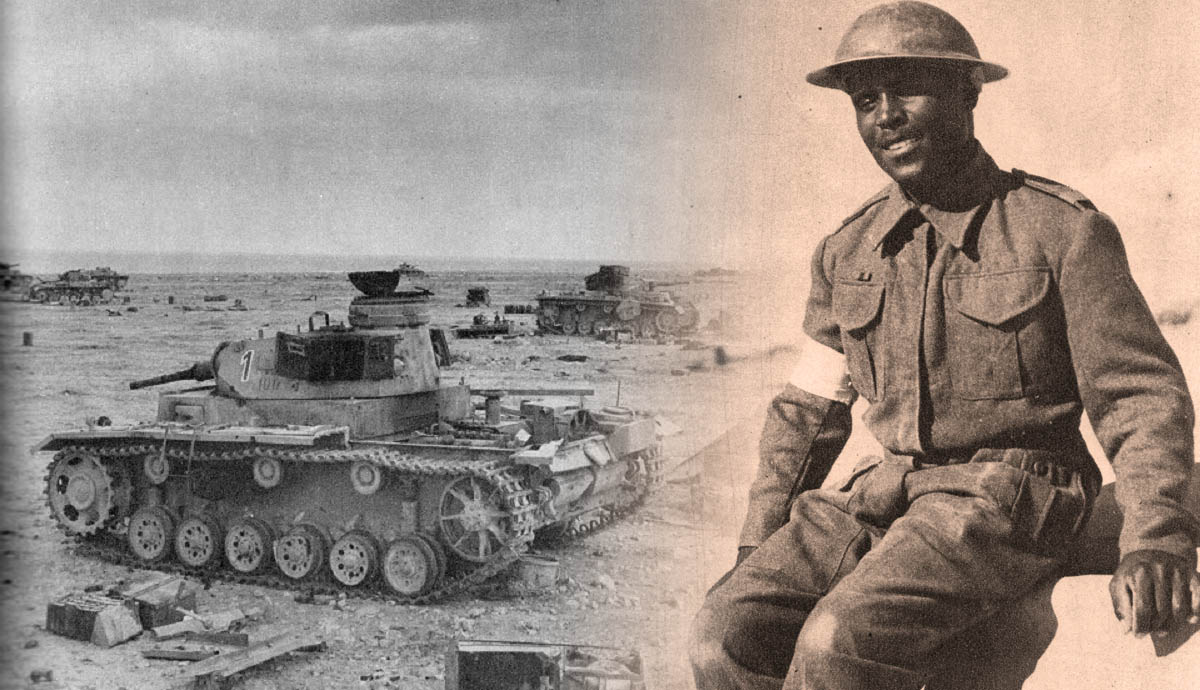

South Africa took considerable part in both the North Africa and East Africa campaigns, both of which began on June 10, 1940, early into World War II and only five days after the fall of France. In East Africa, 27,000 South African troops joined the Allied forces in fighting against the Italians and their allies. During this campaign, the South African Air Force contributed significantly, performing the first Allied bombing run of World War II, a day after Mussolini declared war.

From South Africa’s first engagement at El Wak to the Battle of Gondar, the South African forces proved their worth as effective and resilient soldiers and airmen throughout the campaign, often serving as the vanguard in the first campaign victory for the Allies during the war. The speed and pace with which the campaign was conducted were unprecedented. The final victory cost the Axis forces 230,000 soldiers captured and the loss of 230 aircraft.

With the removal of the Italian presence in East Africa, South Africa would now be able to provide essential supplies to Allied forces in North Africa. However, despite a stellar performance during the campaign, South African forces would face more difficult situations in North Africa.

In East Africa, the South Africans had faced a demoralized enemy allied to tribesmen who had no interest in the war and would break and flee easily. In North Africa, however, the South Africans faced a much tougher, better-trained, and more effective enemy in the German Afrika Korps, led by the skillful Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

The South African troops needed to acclimatize as well as receive extra training for the new conditions. Dogged by transport problems and constant attack by German Stukas, South African forces forced a delay of British operations which led to a rift between South African and British officers.

At Sidi Rezegh in November 1941, the South African forces would encounter their first battle in the North African desert. A failed British offensive ultimately left the 5th South African Infantry Brigade stranded and surrounded on all sides by German forces. Despite dogged resistance and gallantry, which earned much respect from British commanders, the South Africans were completely overwhelmed. They inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, knocking out a significant number of tanks; however, of the 5,800 men who went into battle, 2,964 were listed as killed, wounded, or captured.

This action was an extremely bitter introduction for South Africans to the fighting in North Africa, and it would not be the last. Despite the defeat, the South African damage on Axis forces was critical in providing ultimate success for the Allies in North Africa. Acting Lieutenant General Sir Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie noted that the South African “sacrifice resulted in the turning point of the battle, giving the Allies the upper hand in North Africa at that time.”

Ultimately, the operation was a success. South African troops won significant victories against German and Italian forces at Bardia and Sollum, leading to the neutralization of the Axis threat to the Suez Canal, which was a strategic requirement for success in North Africa.

In mid-1942, The Battle of Gazala took place, wherein Rommel soundly defeated the Allied forces. The British 8th Army was driven west, leaving Tobruk isolated and surrounded by German forces. The garrison consisted of British and South African troops and a small contingent of Indian troops, totaling about 35,000 men. Originally, the intention was to evacuate them, but mixed signals and ambiguous orders led to a bungling of commands. High Command had decided to neither defend nor evacuate the port of Tobruk.

Outnumbered almost three to one, the British High Command had abandoned South Africans again, and the Allied forces were forced to surrender. It was South Africa’s most significant loss in World War II. After the disaster, a British Court inquiry passed the verdict that the commander in charge of Tobruk’s forces, the South African Major-General Hendrik Klopper, was not to blame. Despite this, only seven copies of the verdict were distributed, leaving the reputation of Hendrik Klopper and the South African troops tarnished.

The campaign in East Africa was a complete success, vindicating the South African doctrine of mobile warfare. However, in North Africa, the British command had woefully misused South African capabilities on numerous occasions, leaving South African troops isolated and in a static defensive position.

Nevertheless, South African troops fought on, achieving much success in the coming months, proving their mettle in the engagements up to and including the first and second battles of El Alamein. Resolved to restore their honor, the South Africans fought with particular resolve, taking heavy casualties but succeeding in achieving all their objectives. Of particular importance was the taking of Miteiriya Ridge, where the South African 1st and 2nd Field Force Brigades, despite being pinned down in a minefield while being raked by withering machine-gun fire, refused to break.

Stretcher-bearers worked round the clock, including members of the Black Native Military Corps who ferried their white compatriots to field hospitals, suffering death and injuries in the process. Among these were Lucas Majozi, who, despite having bullet wounds himself, continued to save lives and was awarded a medal for distinguished conduct. Due to South Africa’s apartheid policies, black soldiers were not allowed to fight on the frontlines and were not issued firearms.

From May 5 to November 6, South African troops also took part in the Battle of Madagascar, the first Allied operation to use sea, land, and air forces during World War II. After the fall of France, Madagascar, being part of the French Empire, fell under the control of the Vichy French government and subsequently under Axis control. The South Africans contributed significant air and ground forces to the invasion, which was a success, denying the Japanese a potential foothold in the Indian Ocean.

Italy

In early 1943, after the North African campaign, the South African 1st Division was reconstituted as the 6th Armoured Division. It was to take part in the next phase of the Allied effort in World War II: the invasion of the Italian peninsula.

Initially, the division was ordered to participate in the small-scale operations in Palestine, as South African soldiers had not fully recovered their image from the British Command’s incompetence which tarnished their reputation at Tobruk. This order, however, was countermanded, and, in March 1944, the division began preparations for the invasion of Italy.

South Africans joined and fought alongside British and other commonwealth troops, particularly New Zealanders. Progress was steady and solid. After Rome fell, the South Africans advanced up the Tiber River with impressive speed (10 miles per day). They took Orvieto but suffered a setback when the Cape Town Highlanders were ambushed while trying to take Chiusi. Having heard of this, Jan Smuts made straight to Orvieto to discuss the matter, as the subject of South African troops surrendering was a sensitive topic.

In July 1944, the South African 6th Armoured Division spearheaded the attack to take Florence. After the city had fallen to Allied forces, the hard work they had put in was noted and the division was withdrawn to rest, after which it was reassigned to the US 5th Army.

South African forces fought several engagements along the Gothic Line, and during the Spring Offensive in April 1945, they helped lead the way for the final offensive against the Germans. During their push forward, the South African forces secured all their objectives, engaged in heavy fighting, and destroyed the German 65th Infantry Division. American General Mark W. Clark noted that the 6th Armoured Division was a “battle-wise outfit, bold and aggressive against the enemy.” He added, “Despite their comparatively small numbers, they never complained about losses. Neither did Smuts, who made it clear that the Union of South Africa intended to do its part in the War – and it most certainly did.”

During this time, often accompanying the 6th Armoured Division, was the photographer Constance Stuart Larrabee, the first South African woman war correspondent. Throughout World War II, she documented the harsh conditions soldiers encountered in their fight against fascism.

South Africans in the RAF

Not only did South Africans fight with their own units, but some joined the Royal Airforce and fought for Britain in the skies, many becoming fighter aces. Among these included Marmaduke “Pat” Pattle, who, despite being shot down and killed in 1941, retained the honor of being the RAF’s top-scoring ace even by the end of World War II, and the highest-scoring ace among all the Western Allies. He had 41 confirmed kills in the air, with the actual total probably being closer to 60.

Another famous South African fighter ace was Adolf “Sailor” Malan, who flew for the RAF and gained fame during the Battle of Britain. He was the RAF No. 74 Squadron leader and had 38 confirmed kills in the air. After World War II, he returned to South Africa and joined the Torch Commando, a group dedicated to fighting against proposed apartheid policies.

A Gallant & Worthy Contribution in World War II

South African troops achieved both great victories and major setbacks during World War II. They proved resilient in the face of overwhelming odds and overcame disastrous management, distrust, and slander that threatened to have them pulled away from the frontline. Although South Africa’s contribution was small relative to many other countries, it was nevertheless potent and was a great asset to the Allied cause.