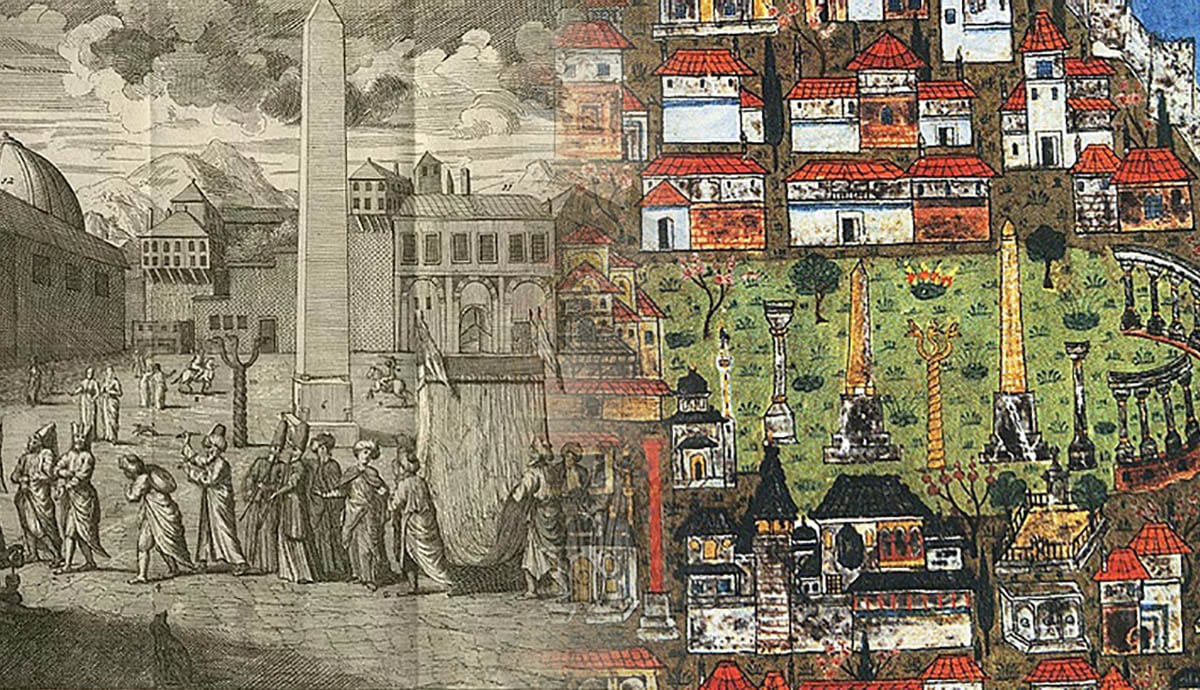

Construction of the Hippodrome of Constantinople began under Emperor Septimius Severus. The monument was greatly expanded by Constantine the Great as part of a wider building project to glorify Constantinople or Nova Roma, the Eastern Roman Empire’s new capital. Eventually reused as the site of Sultanahmet Square by the Ottomans, archaeological excavation has nevertheless revealed much of its original format. The massive grandstands were capable of holding around 100,000 spectators, and the eastern end included a unique viewing area solely for use for the emperor. Throughout its life, the Hippodrome of Constantinople’s spina was home to a wonderful and enigmatic collection of antiquities from across the ancient world. Rather than simply decoration, scholars such as Basset, Dagron, and Bardill have argued each had important symbolic meaning for the new capital of the ancient world.

Theodosius I’s Egyptian Obelisk At The Hippodrome Of Constantinople

Only three of the numerous antiquities on the spina survive in place today, and perhaps the best-preserved is the so-called Theodosian Obelisk. An ancient Egyptian Obelisk originally erected by Pharaoh Thutmose III, the monument was transported to Alexandria by Constantius II. Over three decades later, the obelisk was moved to Constantinople by Emperor Theodosius. The emperor adorned the obelisk with an elaborate base featuring a variety of imperial propaganda. One face depicts Theodosius in his royal box presiding over the games at the Hippodrome. The emperor is shown with his army and attendants and holding a crown as a show of strength. Other faces show the vanquishing of enemies and the surrender of barbarians.

An inscription on the lower face personifies the obelisk and tells how it submitted to Theodosius, echoing the fate of the usurper Maximus. It reads:

“All things yield to Theodosius and to his everlasting descendants. This is true of me too – I was mastered and overcome in three times ten days and raised towards the upper air, under governor Proculus.”

The games at the Hippodrome form the second major focus of the obelisk base. The drawing of lots to determine starting order is depicted, as well a Roman chariot race in action. Numerous musicians and dancers who accompanied the festivities are also shown.

The Statue Of Herakles

The demi-god Herakles may have been represented on the spina by up to three statues. As one of the most famous legendary characters of both Greece and Rome, his heroic feats of strength, intelligence, and endurance would have been a fantastic example for competitors. Herakles was also at home in the sporting arena: he was a common patron of Greek athletic contests and was linked directly with the circus in Roman culture.

One of the statues on display was known as the Lysippan Herakles. Named after the famous third century BC sculptor Lysippos, the statue is taken from the originally-Greek colony of Taras or Tarentum by the Romans. In the early days of the empire, trophies from a defeated nation would be paraded through Rome in a military triumph. In the later period, spolia is used to demonstrate the power of Roman dominion and her free will to take what she pleases from her subjects.

Constantine’s Walled Obelisk

The second obelisk in the Hippodrome of Constantinople also survives today. However, earlier antiquarian images show it had lost much of the facing stone and become dangerously precipitous before it was restored in the modern period. The Walled Obelisk was probably also erected by Theodosius but was created by Roman sculptors to mirror the Egyptian example on the other side of the spina. Originally Rome was the only imperial city that allowed two obelisks. The addition of the walled obelisks demonstrated the rise of Constantinople as the new imperial capital. In the later Byzantine period, Emperor Constantine VII decorated the monument with bronze plaques that would have dramatically reflected the sun. A contemporary dedication calls the obelisk a brazen wonder and likens it to the ancient Colossus of Rhodes.

Statue Of The White Sow With Piglets

A lesser-known feature of the Hippodrome’s spina was a sculpture of a white sow with piglets. When Aeneas, the mythical founder of Rome, fled Troy, he was told by Helenus he would found the city where he encountered a white sow with 30 piglets. Once on the coast of Latium, Aeneas prepared to sacrifice a white sow from his ship. The pig escaped, and the Trojans later found the beast, which had been pregnant, under a tree with 30 piglets. The display of a monument specifically linked with Rome showed Constantinople was legitimizing itself by reference to the old capital. The source of this spolia is unknown. However, if taken from Rome itself, it would be a dramatic indication of the transfer of power.

Statue Of Romulus And Remus With The She-Wolf

A second monument linked with the old imperial capital was a statue of Romulus and Remus with the she-wolf. In the famous story of Rome’s origins, the brothers were raised by a she-wolf but later clashed over which hill should be the location of their new city. Statues of the brother’s and she-wolf are used today throughout the world to signify a connection with Rome, so the effect of the statue on the spina is clear. Combined with the sculpture of the sow and piglet’s Constantinople was advertising itself as the new Rome. The she-wolf statue also served another purpose by linking the Hippodrome of Constantinople to the Lupercalia festival, which would be celebrated in the area, and showing the site was a focal point for imperial ceremonies.

The Serpent Column

The unusual Serpent Column survives in a damaged form in Sultanahmet Square today. Used as a fountain at some time in recent history, today it is protected by an iron fence. The Serpent Column was removed from its previous location at Delphi, Greece. The monument originally consisted of three intertwined snakes surrounded by a gold tripod and supporting a sacrificial bowl. By the time it was removed to Constantinople, only the snakes had survived. Although the animals were shown with heads in medieval depictions, these were subsequently removed or broken. The top half of one has been recovered during recent excavations.

The Serpent Column was originally a victory tripod commemorating the Greek victory at Plataea in the Persian Wars. By displaying the monument in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, the Eastern Roman Empire was legitimizing itself as the heir of Greek lands. Similarly, the monument’s original meaning could be adapted to match the empire’s victories of barbarians or the Sassanid Empire – the heirs of the ancient Persians. Alternatively, the Serpent Column could simply be displayed as a trophy from closing the Delphic oracle and the triumph of the new Christian religion.

Statues Of Mythical Creatures And Animals At The Hippodrome

Perhaps the more unusual monuments to be displayed on the spina of the Hippodrome of Constantinople were apotropaia, or statues of animals and traditionally pagan mythical beasts. These included Hyenas, dragons, and sphinxes. Of the numerous monuments in this category, only a goose has survived today, and statue bases are the only surviving evidence of the rest. However, they are listed and depicted in medieval accounts and drawings.

Despite the overtly Christian setting, these images were possibly still believed to serve a spiritual purpose. Wild and mythical animals, whilst normally evil, were believed to use their powers against bad spirits and help maintain order when captured and harnessed in a civilian setting.

The Bases Of Porphyrius, Roman Charioteer

The most famous athlete in the Late Roman world was Porphyrius the charioteer. Porphyrius raced throughout the Eastern Empire but had most of his success at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. Roman chariot racing was often divided into teams of color, the famous being ‘the greens’ and ‘the blues.’ The teams provided employment for locals in the form of assistants, as well as musicians and dancers. However, such was the rivalry between the respective fans that riots would frequently break out.

Porphyrius was the only Roman charioteer known to have won the diversum, the act of swapping teams after one victory and then subsequently winning for the opposing team, twice in one day, For this and his other exploits he had Porphyrius Bases erected for him on the spina alongside the other antiquities. The bases once held statues and are elaborately decorated. Depictions include various factions waving their support, Porphyrius swapping horses to win a diversum, and the man himself standing in his quadriga celebrating victory. They were at least 10 bases erected, which show the importance, passion, and excitement of Roman chariot racing at the time. Controversially, however, much of the imagery evokes imperial scenes on the Theodosian obelisk, and the Laws of Theodosius recognized this threat to authority by forbidding Roman charioteer statues to be placed next to those of the emperor.

Statues Of Pagan Deities At the Hippodrome Of Constantinople

Numerous pagan deities were displayed on the spina and often had associated altars alongside them. Prominent examples included Artemis and Zeus, and the twin gods Castor and Pollux. As with the mythical creatures discussed above, pagan statuary has served a purpose beyond just display.

Artemis and Zeus had ancient associations with horses and breeders. In earlier times they may have acted as patron gods of competitors, but were still seen to bring good fortune. Castor and Pollux were traditionally depicted as athletes. They were long associated with the circus and games and perhaps formed another link with Rome. From a ritual perspective, the repetitive and circular nature of the Roman chariot races could be linked with natural and seasonal cycles, and in an imperial context the perpetual rebirth of the city of Rome.

The Quadrigae Or Horses Of St. Mark

Perhaps the most famous antiquities from the Hippodrome of Constantinople are the Horses of St. Mark, a group of four horses that were likely originally associated with a chariot. The 8th century Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai suggests that originally the horses were brought from Chios by Theodosius II. Although their origin is unknown, the detail of the sculptures implies a Late Roman date is unlikely. The horses have traveled greatly since their time in the Hippodrome but likely stood on a column high above the spectators and starting boxes, directly referencing the Roman chariots and horses below.

Following the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade the horses were removed to Venice and placed above the porch of St. Mark’s Basilica. The sculptures were looted by Napoleon in 1797 but were returned less than 20 years later, and are currently undergoing restoration. Their display at the Hippodrome of Constantinople reinforced the complex’s status as a fitting successor to Rome’s Circus Maximus and provided a sense of respectability that a Late Roman building may otherwise have lacked.