IRA stands for Irish Republican Army. The term that best sums up the history of the IRA, the undisputed protagonist of recent Irish history, is “breakaways.” After the several splits the IRA has undergone since 1919, the term doesn’t designate a single group anymore but refers to the various paramilitary groups that have pursued nationalist (and republican) goals through armed struggle in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in the 20th century. Tracing the history of the Irish Republican Army, from the “old IRA” to the Provos and the New IRA, is equivalent to tracing the history of Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

The “Old IRA” (1919-1922)

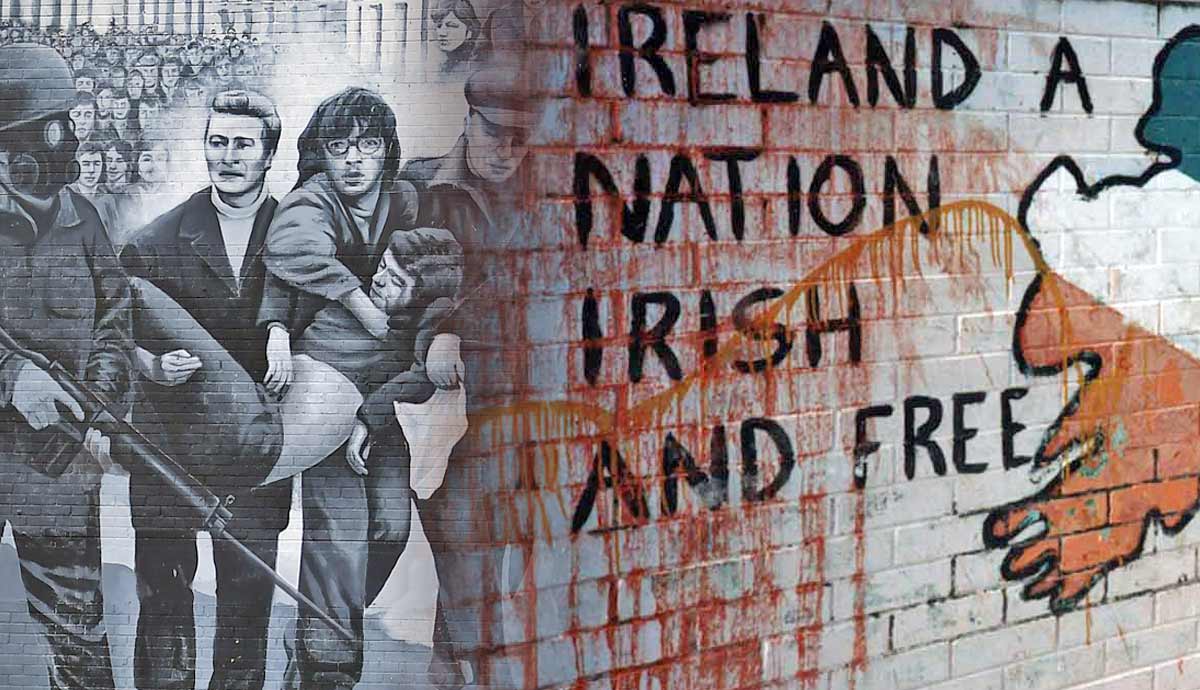

The history of the IRA is closely tied to the Partition of 1921, that is, the division of the island of Ireland into two separate entities: the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland, also known as the Six Counties, comprises six counties, four of which (Fermanagh, Tyrone, Derry, and Armagh) share a border with the Republic.

Protestants and loyalists often refer to Northern Ireland as Ulster. Prior to the Partition, Ulster was a culturally distinct region from the rest of Ireland (the others being Munster in the South, Leinster in the East, and Connaught in the West). Ironically, Ulster was the most Gaelic of the four provinces, both culturally and linguistically. In the 17th century, when British King James I initiated the settlement of Scottish Presbyterians and English Protestants in the region, Ulster slowly but steadily became predominantly Protestant.

During the decades that followed, English and Scottish Protestants gradually took over land inhabited by Irish natives. This act of dispossession fueled a division between (Catholic) nationalists, who wished Ireland to be independent, and (Protestant) unionists, who staunchly defended their right to remain part of the United Kingdom.

The 1916 Easter Rising rebellion was a turning point for all four Irish regions. It showed the world (and especially Great Britain) the determination of the Irish people to be independent while solidifying Catholics and Protestants in their opposing beliefs. While the southern provinces celebrated the Easter rebels as heroes, people in Ulster viewed the rebellion as an act of treason against Great Britain during a time of war.

Back to the IRA. The Irish Republican Army active between 1919 and 1922 was led de facto by Michael Collins (and officially by Cathal Brugha). It is now known as the “old IRA,” or “original IRA,” and its origins can be traced back to the Irish Volunteers, the organization, founded in 1913, that was responsible for the Easter Rising.

By late 1919, the members of the Irish Volunteers who recognized the authority of the first Dáil Éireann (Assembly of Ireland) started calling themselves members of the “Irish Republican Army.” The “old IRA” was born.

The signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921 not only ended the War of Independence (1919-1921) by establishing the Irish Free State (and Northern Ireland), but it also led to the first split in the history of the IRA.

The Irish Republican Army (1922-1969)

In 1922, the IRA members opposed to the signing of the Treaty broke away from the IRA and formed the anti-treaty IRA sub-group. This was the beginning of the Irish Civil War, which lasted from 1922 to 1923. During this time, the anti-treaty IRA waged war on the Irish Free State (which always maintained they were “Irregulars”), burning public buildings, and destroying bridges and railway lines.

When they seized the Four Courts in Dublin in April 1922 Michael Collins’s pro-Treaty forces bombed them. The anti-Treaty IRA eventually became outnumbered, and by August 1922, the Free State had regained control of all the major towns with the help of the Dublin Guard, a unit made up of highly trained and motivated former IRA men loyal to Collins. Finally, on May 24, 1923, Frank Aiken, chief of staff of the Anti-Treaty, called for a definitive cease-fire. The Irish Civil War finally came to an end.

After the Civil War, the IRA continued to resist the Irish Free State and the Partition of Ireland. When Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil party won the elections in 1932 a more relaxed and friendly relationship began between the institutions and the IRA. However, it was short-lived, with the IRA denouncing de Valera’s party for not seeking to end the partition of Ireland. In response, de Valera banned the IRA in 1936 in what was the beginning of his increasingly strict anti-IRA policy.

Public support for the IRA was relatively low during World War II. The IRA’s political stance can be summed up as “The enemy of my enemy is my enemy.” Despite Ireland remaining neutral, the IRA declared its support for Nazi Germany in the hopes of weakening the British position.

During the war, both the British and Irish governments took measures to imprison and even execute members of the IRA. As a result, by 1945, the organization was a shell of its former self, with only 200 active members left. However, two years later, a new leadership emerged and managed to resurrect the organization by tying it to the Sinn Féin political party and focusing on the situation in Northern Ireland.

They also carried out several raids on British military bases across Northern Ireland, in Derry, Armagh, and Omagh, as well as in Great Britain, in Berkshire and Essex, between 1951 and 1954, in order to re-arm themselves. Finally, in December 1956, the IRA launched Operation Harvest, also known as the IRA’s border campaign.

The campaign, devised by Seán Cronin, lasted over five years and saw Republicans launch a series of attacks on military and infrastructure targets (courthouses, Army barracks, BBC relay transmitters, and RUC stations) within Northern Ireland. In the 1930s and 1940s, the IRA’s declared aim was to overthrow both British rule in the north and the Irish Free State, which they saw as “alien” and illegitimate institutions imposed upon them by the British.

In the 1950s Republicans shifted their focus to Northern Ireland alone. Although the border campaign ultimately failed, it represented a watershed moment in the history of the IRA. While the tensions resulting from its failure were one of the causes of the split of 1969, they also prompted a rethinking of the organization’s strategy. The IRA’s leaders understood that they needed to seek and gain popular support if they were to achieve their goal of a unified Ireland.

The IRA Becomes the Provisional IRA (1969-2005)

The outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland marked a new and complex beginning for the IRA. Popular support fluctuated during the 1950s, as many felt that the IRA had failed in its objective to protect Catholic communities. After the August 1969 riots (which marked the beginning of the Troubles) and the massive deployment of British troops on Northern Irish soil, the Irish republican movement was divided on how to respond to escalating violence.

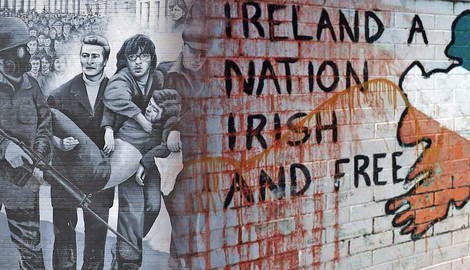

The so-called Provisional IRA emerged in December 1969 as a breakaway (minority) faction of the original IRA. In less than two years, the Provos (as it was called) became the primary Irish republican paramilitary force involved in the armed struggle to end British rule in Northern Ireland. Then, in January 1972, the events of Bloody Sunday outraged the world. In the tragic days that followed thousands of young Northern Irish men and women voluntarily joined the ranks of the Provisional IRA.

Support for the IRA continued to wax and wane in the late 1970s and 1980s, particularly after some of the deadliest attacks it carried out. The 1978 La Mon House bombing, for instance, killed twelve innocent people after a bomb caused a devastating miniature-type firestorm that spread throughout the hotel’s rooms. Similarly, the so-called Remembrance Day attack in Enniskillen in 1987 resulted in twelve deaths and 63 people injured, some of them permanently. In both cases, all the victims were Protestants.

Especially in the aftermath of the La Mon House attack, support for the IRA drastically declined both in Ireland and overseas. The president of the Sinn Féin, the political wing of the IRA, publicly condemned the group’s careless disregard for innocent lives and the IRA admitted responsibility.

1978 became the worst year for the IRA in its history. However, the tide changed in 1981 with the hunger strikes in the Long Kesh prison, and support for the IRA began to grow again.

Over the years, many crucial leaders merged from the ranks of the Provisional IRA, including Martin McGuinness (1950-2017), second-in-command in 1972, at the time of the Bloody Sunday, and Gerry Adams (1948). Both McGuinness and Adams played pivotal roles in the negotiations that led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which was publicly acknowledged by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who was also involved in the peace process.

In April 1994, the first ceasefire was announced. It lasted two days. Four months later, on August 21, 1994, another “cessation of military operations” was announced, which lasted until February 1996. It was renewed in July 1997, shortly before the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. After years of disagreement over decommissioning, in 2004, the IRA officially announced the end of its armed campaign.

How Many Deaths Is the IRA Responsible For?

Over 30 years, 3,720 people lost their lives as a result of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, according to CAIN. They were victims of bomb attacks, shootings, being run over (the Maguire children in August 1976), kidnappings and torture (the victims of the Shankill Butchers), and premature explosions (which happened occasionally to members of paramilitary groups on both sides). Data provided by Wesley Johnston show the Provisional IRA was responsible for 49% of the killings.

Out of the 1696 people who died because of the IRA’s attacks, 790 were Protestant, 338 Catholic and the rest came from outside Northern Ireland. Other sources estimate that the IRA killed between 1,700 and 1,800 people, not only in Northern Ireland but also in the Republic of Ireland and on British soil. It is important to note that the Provisional IRA was not the only republican group active during the Troubles.

Some of the killings were also carried out by the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) and by the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA). The Catholic community was the most affected, with 1525 people killed, according to Malcolm Sutton. Additionally, most of the civilians killed by British forces (that is, the British Army, the Royal Ulster Constabulary, and the Ulster Defence Regiment) were Catholics, a fact that underlines the sectarian nature of the Northern Irish conflict.

In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed and welcomed by most paramilitary groups, as well as by the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. However, some members of the Provisional IRA opposed the Agreement and broke away in 1997 to form the so-called Real IRA (RIRA).

In 2012, the Real IRA merged with other republican groups, including Republican Action Against Drugs (RAAD), to form a new organization called the New IRA. On April 18, 2019, Belfast-born journalist Lyra McKee was shot dead while covering a series of riots in the Creggan neighborhood in Derry. She was 29. She died doing her job, which was to investigate and expose the consequences of the sectarian conflict that had plagued Northern Ireland from 1969 to 1998. The conflict still affects tens of thousands of people today. The New IRA admitted responsibility for her murder. Their power base is in the Creggan area of Derry, where McKee was murdered. The New IRA’s main target remains the men of the PSNI, the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

In 2023, the United States added the New IRA to the list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations. In a way, McKee’s death is the result of that very same sectarian mentality that allowed the Troubles to claim victims for 30 years. The articles and investigative work she carried out tell another story — that of a country that is actively working towards peace to leave the violence of the Troubles in the past.