Syphilis is an infamous disease that has been stigmatized throughout history because of its believed links to immorality and divine punishment. While we now know that these were misconceptions, there is no doubt that the disease still caused a great deal of pain and discomfort for people in the past. Here are 10 crazy facts about the history of syphilis.

1. Mercury was Used to Treat Syphilis

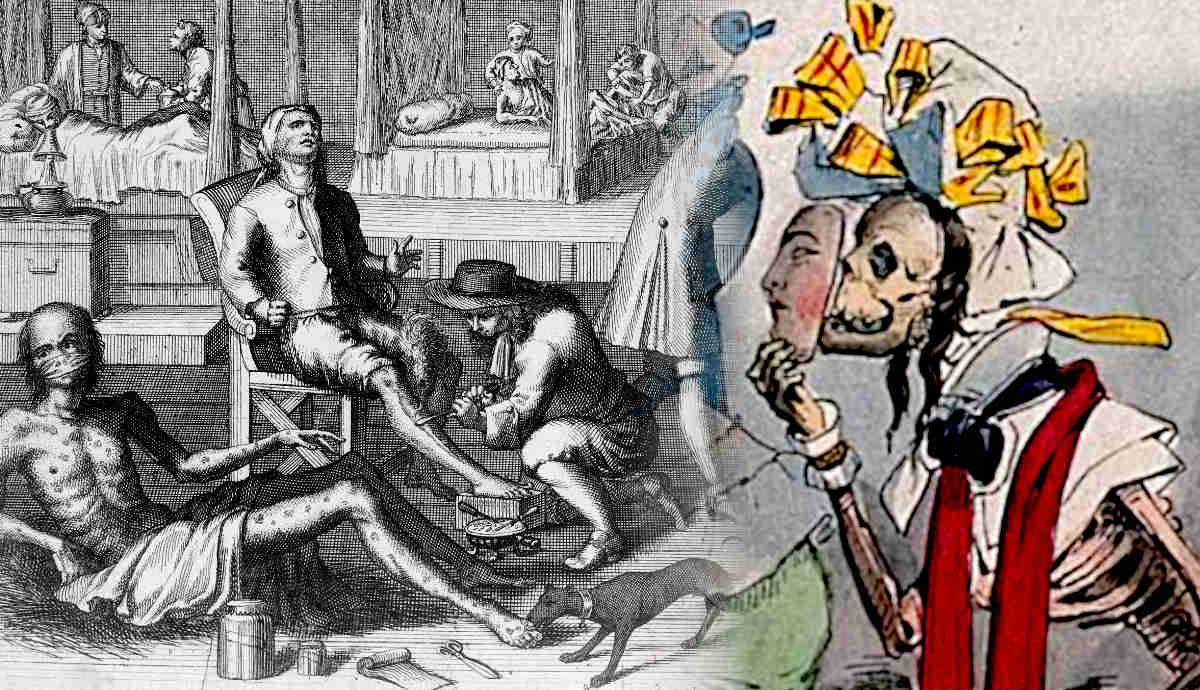

One of the most unbelievable facts about syphilis is that it was often treated using mercury. This incredibly harmful substance was most commonly applied directly to the affected areas via inunctions (ointments) but could also be administered via pills or steam baths.

Of course, this was incredibly dangerous and often did more harm than good, as mercury could cause several painful side effects, including mouth ulcers, tooth loss, and kidney failure. In fact, it could be so dangerous that mercury caused more deaths among syphilis patients than the disease itself.

Syphilis was not the first disease people attempted to cure with mercury. The substance had been used in a whole plethora of medications for conditions including constipation, flu, parasites, and melancholy. As early as 1363, the physician to the Pope, Guy de Chauliac, mentioned the benefits of its use in treating disease in his La Grande Chirurgie.

2. No One Really Knows Where or When Syphilis Originated

While the first documented outbreak was in the 1490s, when Charles VIII of France went to war with Italy, the actual biological origins of syphilis are still unknown and hotly debated.

There are two main theories that disagree over how and when the disease first existed. One argues that Columbus and his crew brought it to the European continent after their expedition to America in 1492. Commonly called the Columbian hypothesis, it cites written documents from their return trip that record some of the crew being ill with syphilis-like symptoms labeled simply as an “unknown disease.”

The other theory argues that syphilis had existed in Europe (and the rest of the world) long before Columbus went to America and that it had just gone unnoticed. Evidence for this theory was found in 2020 when the skeleton of a woman who had suffered from a disease similar to syphilis almost 10,000 years ago was discovered in Mexico.

3. Europeans were Superspreaders

The first concrete evidence of a syphilis outbreak comes from the summer of 1494 when King Charles VIII of France marched his 50,000-strong army across the European continent and went to war with Italy.

As the French advanced, soldiers “celebrated” their victories, and with this came the appearance of a mysterious, painful, and incredibly uncomfortable disease. Then, when soldiers returned to their homes or the victims of their celebrations returned to theirs, they took this new and deadly disease with them.

This was how syphilis spread across Europe. It soon reached France, Switzerland, Germany, and eventually, both England and Scotland.

It was then spread around the world by European explorers and colonizers. By 1498, syphilis was in Calcutta, and it was in Africa, China, Japan, and even Oceania by 1520.

While there is some debate over whether the Europeans were the first cause of syphilis in these countries, there is no doubt that, even if they did not bring it over in the first place, they certainly made it a lot worse.

4. Syphilis had Lots of Nicknames

Syphilis was given many nicknames that originated as a result of the stigma surrounding the disease. People took to naming it after individuals they were not particularly fond of as an insult.

So to the French, for example, it was the “Neapolitan disease,” to the Polish, the “German disease,” and to the English, the Germans, and the Italians, it was referred to as the “French disease.”

It is thought that one of the first uses of the actual word “syphilis” was by the Italian poet and physician Girolamo Fracastoro in a poem entitled Syphilis sive Morbus Gallicus published in 1530. It tells the story of Syphilus, a shepherd who cared for the sheep of King Alcinous (from Greek mythology). In brief, the god Apollo becomes mad when Syphilus refuses to do as he wishes and proceeds to curse humanity with a horrible disease named syphilis, which he named after the shepherd who had made him so angry.

5. Before Modern Medicine, the Disease Could Last for Years

The first effective treatment of syphilis came in 1906 with the development of the Wasserman blood test. Before this, however, the disease would be diagnosed based purely on the visible symptoms it caused, like rashes and chancres.

Because of this, it either went undiagnosed for a long time or was treated ineffectively, which meant it was never cured.

In its early history, syphilis had three distinct phases. The first involved genital sores and the second involved a generalized rash with fevers and aches, which could last sporadically for months or even years.

The third phase involved abscesses and ulcers. If the disease progressed to this point, it would often end badly – either with severe disability or death. It was from this phase that much of the stigma surrounding syphilis arose because of the visible disabilities it often left people with.

All in all, the disease could last for years and became a great source of pain and discomfort for its sufferers.

6. Henry VIII Established Public Health Measures to Control the Spread of Syphilis

In England, King Henry VIII (1491-1547) took early action against the disease.

Because syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease, it quickly became associated with sex workers who themselves were already heavily stigmatized for their supposed immoral behavior. Because of these stereotypes, Henry VIII decided it was necessary to close down all the brothels and bathhouses in London.

While the motivations behind such actions were misguided, since syphilis is spread through direct contact with the affected area rather than corrupted morals or immoral behavior, they were somewhat effective in that they prevented close, often intimate contact among strangers.

Henry VIII was not the only European monarch to take such action. In other countries, similar regulations were placed on people’s free time. Consequently, many sex workers who were already mistreated and poor were left without work and money.

7. Syphilis was Often Seen as Punishment from God

Many diseases in the early modern period were believed to be linked to God’s intervention. However, this was particularly the case with syphilis because it was already heavily linked to moral issues.

Many believed that syphilis was a punishment from God. Some went as far as to argue that the appropriate treatment was, therefore, more punishment, or in some cases, it shouldn’t be treated at all and that they should be left to suffer as God had intended.

Not all, however, subscribed to this notion. A British physician named Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) argued in 1673 that physicians had no part in involving themselves in the morals of their patients and instead should simply treat them as needed without judgment.

8. Syphilis was Often Confused with Gonorrhea

Before our modern scientific understanding of syphilis developed, diagnosis was based on visual symptoms. It was, therefore, extremely common for syphilis to be mistaken for gonorrhea or vice versa.

Both are bacterial infections, and although the bacteria at their roots are different, they have similar symptoms, leading to their frequent confusion.

It wasn’t until at least 1761 that physicians began to realize the two were separate diseases. In that year, the anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) wrote in his De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis that the symptoms of the two diseases were caused by separate ailments.

However, some continued to debate, and it wasn’t completely put to rest until a French physician, Philippe Ricord (1800-1889), rather conclusively argued that the two were separate in 1838. He provided evidence that the stages of syphilis differed from that of gonorrhea. Because of his work, the primary lesion that forms on a patient with syphilis was named “Ricord’s chancre.”

9. Experiments were Performed on Sex Workers

As previously mentioned, sex workers were heavily stigmatized when it came to sexually transmitted diseases. Because of the nature of their work and the primitiveness of sexual healthcare at the time, they were the demographic most often hospitalized with syphilis.

This, therefore, meant it was to them that doctors and scientists looked for answers.

These medical men conducted experiments in what has been termed “syphilization,” which was based on the theory of inoculation. Much like the very early smallpox vaccinations, it was believed that by having the disease once, the patient would then be immune to having it a second time.

Physicians, therefore, attempted to infect sex workers with the disease in the hopes that having the disease once would encourage natural immunity. Unfortunately, for many sex workers, this was not the case. Many were given the disease for the first time through these experiments and then died or were permanently disfigured when they were unable to recover from it.

10. Not All Early Treatments were as Deadly or Toxic as Mercury

Another method of treating syphilis was guaiacum (nicknamed “Holy wood”), a type of wood from the Dominican Republic. It was one of the first drugs to treat syphilis when it was imported to Europe in 1508. It could be used in a variety of ways, from the bark itself to the other plants and flowers in the guaiacum genus.

People raved about the “miracles” it could cause, and it quickly became a favorite treatment (aside from mercury) for many European physicians. In 1588, Johannes Stradanus (1523-1605), an artist working for the Medici family, depicted the substance in one of his engravings (as seen above).

There were some disagreements over how the wood should be administered. Some recommended that it be boiled in water, others that it be grated or cut up. Others argued over the type of water it should be added to, some arguing for river water, others arguing for well water.

According to some sources, it was so popular in the 16th century that 10 tons a year were imported to Livorno alone!

In conclusion, syphilis was a disease that not only caused great pain and suffering but also carried with it a stigma that could destroy reputations. It was very rare that people would ever completely recover from the disease, and many were left with physical scars, which meant they were judged and treated poorly for the rest of their lives.