Shared by Chile and Argentina, Patagonia is inconceivably beautiful, home to sky-reaching Andean peaks, glacial lakes, and spectacular prime forests. It is the last landmass separating the continent from Antarctica. It is also a harsh and incredibly inhospitable land that has—perhaps surprisingly—been inhabited for thousands of years.

Some of the world’s oldest prehistoric art has been found in its caves, and some of its most forgotten indigenous tribes lived their last moments on its steppes.

Pre-Columbian Patagonia

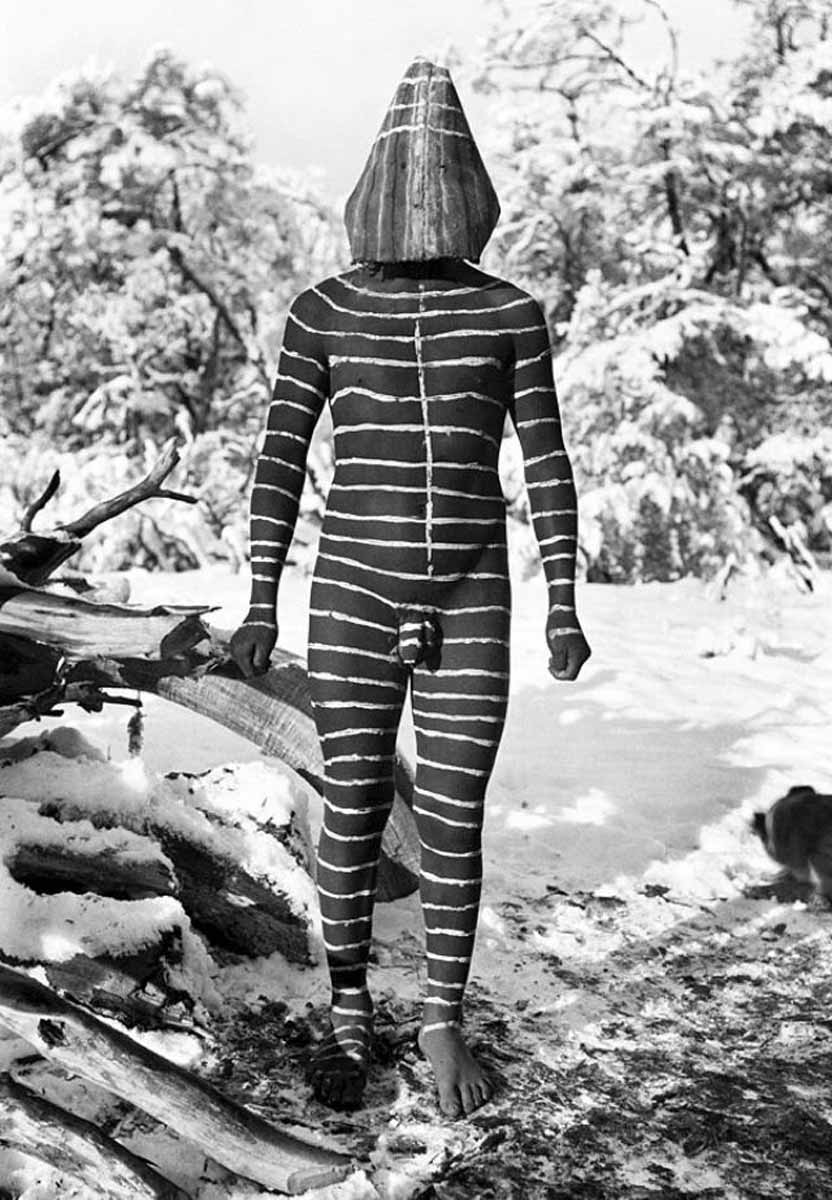

Patagonia was home to various indigenous tribes long before Europeans arrived. Among the half-dozen or so tribes spread around the region, the Selk’nam was the largest and most established. Also known as the Ona People, they were particularly distinct for their rich culture and unique customs. They inhabited the windswept landscapes of Tierra del Fuego for over 6,000 years, living a nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Although their lifestyle seemed primitive to the first Europeans, it was anything but. They held elaborate ceremonies, including the Hain, an extravagant initiation ritual that marked a boy’s transition to manhood.

Like their northerly neighbors, the Aztecs, Maya, and Inca, the Selk’nam believed in a complex spiritual world where every element of nature held deep meaning. Yet, unlike most other tribes, they believed in one primary deity—a god that superseded all others. They weren’t the only ones with a monotheistic belief system but it was certainly a rarity in Pre-Columbian Latin America.

The Selk’nam were among the last indigenous inhabitants in the Americas to encounter Europeans. Once the latter made it that far south, in the late 19th century, it marked a catastrophic turning point for all the indigenous tribes of the region—much as it had done in the north. Many tribes had their numbers decimated by diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis, with the remainder succumbing to violence and the relentless expansion of sheep farming that devastated their livelihood. The Selk’nam, on the other hand, were first subjected to degrading treatment before being decimated.

Paraded as expedition curios, indigenous Selk’nam tribespeople were snatched from Patagonia to be exhibited in the human zoos that were all the rage in Europe in the late 1800s and early 20th century. The Selk’nam were the most exploited, yet tribespeople of Patagonia’s southern coastal region (the Yaghan) and the Kawésqar, who lived in the region’s fjords, were also forcibly removed and taken to Europe to be exploited.

Among modern-day historians, the Selk’nam are recognized as one of the hardiest and most formidable ancient tribes to have ever lived anywhere. These were strong, tall, adaptable, and capable people who built an incredible culture, an impressive legacy, and an intricate social structure. They survived in the harsh Patagonia wilderness for thousands of years, wearing animal skins. They never took to agriculture but had pet dogs, never fished but hunted with clinical precision.

Incidentally, the southernmost island in Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego (the Land of Fire in Spanish), was named by Europeans after the massive bonfires they saw when they first set foot on the island. These humongous flares were a survival strategy of the Selk’nam and how they managed to thrive even through the unforgiving Patagonian winters.

Less than 100 years after the European arrival, the tribe all but disappeared from the face of the earth. The last known, full-blooded Selk’nam died in 1974, and their language was declared extinct in 1990.

European Arrival in Patagonia

The Patagonia we know today has been deeply marked by European influence. Starting with the names of prominent places. Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan is credited with naming Patagonia—a derivative of “big-footed people” in Spanish—when he sailed through the Strait of Magellan in 1520. He arrived in the region right at the peak of the Age of Exploration—a time in history when intrepid European explorers set off to “discover” the world beyond their horizons.

Following in Magellan’s footsteps were several explorers, among them Sir Francis Drake. Tales of spectacular, uncharted landscapes and fascinating indigenous tribes enticed them. The underlying primary draw, however, lay mainly in the stories of abundant natural resources. Patagonia’s vast grasslands were ideal for livestock grazing.

The birth of sheep farming irrevocably transformed Patagonia’s landscape, culture, and economy. Expansive ranches, called estancias, were initially established by Scottish settlers, leading to an influx of European immigrants. Yet life in Patagonia was not nearly as idyllic as they’d been led to believe, and that’s part of the reason the region was never fully inhabited and developed. Not the way the north was, anyway.

Today, part of the challenge of exploring Patagonia is that the region—being so immensely vast—isn’t completely developed. On the contrary, settlements and towns are few and they are far apart. The vast expanse of spectacular, unspoiled wilderness is what makes it so incredibly special.

Patagonia: Inspiring Artists Since Antiquity

Patagonia is an inspiring place to visit and its art scene is evidence of its eclectic history, from intricate basketry and textiles made by the Selk’nam to the stunning landscape paintings by early European artists. Yet the most prized art is still ancient and indigenous—the so-called Rupestrian art of Patagonia is UNESCO-listed and is the oldest rock art ever found in South America. It is a collection of hand paintings of humans and animals in some of the region’s remotest caves.

19th-century Patagonia: The Birth of Industry & Settlements

Sheep farming significantly changed Patagonia and displaced many indigenous communities. Although the Argentinian and Chilean governments offered them land elsewhere, most refused to leave. This resulted in violent expulsions, like the Conquest of the Desert in 1870, which led to the deaths of around 20,000 people, mainly from the Tehuelche and Mapuche groups.

Patagonia in the 20th Century

While land grabs and expulsions continued into the early 1900s, major construction ramped up in the 1950s and 60s, when roads and ports were built and existing settlements expanded. Tourism had its tentative beginning around this time, too, as word of the region’s exquisite landscapes started spreading. However, primarily intrepid travelers and scientists braved the elements and the minimalist tourist infrastructure.

‘70s-‘80s: Nature Enthusiasts Arrive

The boom of the backpacking and mountaineering scene put Patagonia on the global map. Attracted by an array of spectacular peaks, like FitzRoy and Torres del Paine, adventure-seeking tourists began arriving in earnest in summer every year. From this initial peak, Patagonia was marketed as a thrill-seeker’s paradise. Trekking and mountain climbing facilities were set up in strategically located towns, close to the Patagonian Ice Field and the sensational spine of Andean peaks that have now become the poster kids for the region.

The Birth of Ecotourism & an Unlikely Ally

The ‘70s-‘90s brought a conservation boom, with a big focus on protecting Patagonia’s wild beauty. National parks like Los Glaciares, Torres del Paine, and Nahuel Huapi were established to preserve its superb landscapes. One of the most influential conservationists was Douglas Tompkins, the founder of North Face. Alongside his wife, Kristine, Tompkins purchased colossal areas of degraded wilderness, which they restored and then donated to the Argentinian and Chilean governments to be protected. Their efforts sparked debates around who should control this land and how it should be used—and if it was even ethical that a foreigner be allowed to purchase so much land.

Opinions differ, but there are undisputed facts: the Tompkins’ efforts have protected a mind-boggling 14 million acres of Patagonia’s wilderness. Their actions have led to the creation of four major national parks in the region: Pumalín, Corcovado, Ibera, and Patagonia National Park.

Patagonia in the 21st Century

Ecotourism has reshaped Patagonia in the last two decades. It is now one of South America’s premier tourist destinations and, despite boasting a relatively short “peak” season (October to March), it welcomes over 700,000 tourists yearly. All are keen to experience its glaciers, mountains, and rare wildlife. Despite the efforts of dedicated conservationists, however, land exploitation and indigenous displacement are issues that persist to this day.

Descendants of the Mapuche are among the most outspoken, with many fighting big corporations (and their governments) for the right to reclaim their sacred land. The situation continues to be volatile, and particularly vocal indigenous rights activists frequently go missing in the region. The case of Santiago Maldonado was probably one of the most famous in recent years.

Patagonia is facing significant challenges, including high demand for its natural resources such as water, oil, gas, and timber. The region is also suffering from the effects of climate change, particularly shrinking glaciers that often make headlines. Despite these issues, there are several conservation projects working to protect Patagonia’s valuable wilderness and history.