With the first 20 Africans brought to Virginia in 1619, the United States initiated a labor system characterized by extreme oppression and violence. But slavery was not just about labor and the economy—it permeated every aspect of the country’s political, social, religious, intellectual, and moral structures, values, and sentiments. On the eve of the Civil War, there were 4 million enslaved people, and although most of them were not able to carry out widespread rebellions or escape to the North, they demonstrated immense fortitude and resilience in the face of unimaginable cruelty.

Slavery in the Colonial Period

Founded in 1607, Jamestown was the first formal British colony in the New World. It faced difficult early years as settlers adjusted to harsh weather, disease, and the necessity of creating sustainable housing and economic infrastructure, but it soon prospered, especially when tobacco became a major export crop. Much of the initial labor force throughout the 17th century were indentured servants: British men (and some women) who signed contracts with wealthy planters who then paid their passage over in return for working their land for a period of time, after which they were released and ostensibly gained land of their own. Indentured servitude proved an untenable labor system for many reasons, and the shift to slavery began in earnest by the 1680s.

The first enslaved Africans arrived in Jamestown in 1619, and by the end of the 17th century, every colony had slavery. New England and the Middle Colonies had fewer enslaved people, as the climate and terrain did not necessitate the same degree of agricultural labor as the Southern colonies, which were growing tobacco, rice, indigo, and other exportable goods. The Southern colonies, which eventually included Virginia, Maryland, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia, at times had more enslaved people within their borders than whites. Slaves were an integral part of the colonial economy; the colonies would not have prospered as they did without their forced labor.

Early colonial slavery was somewhat less rigid than late colonial slavery, as there were some opportunities to earn freedom, and the slave codes had not yet become explicitly tied to race. But as the 18th century wore on, slave codes became more punitive and directly connected skin color to bondage. For example, a child born to an enslaved woman inherited the status of the mother—meaning that whether sired by a Black man or a white enslaver, every child born to an enslaved mother was also enslaved.

Enslaved people sought to create a life for themselves amidst unfathomable oppression. They brought over religious, cultural, and culinary traditions from Africa, melding them with those from Europe. They persisted in developing familial and communal ties, even when the difficulties in forming and maintaining them were enormous, and resisted their bondage in small ways and large.

The Revolutionary War and Its Aftermath

The American colonies went to war with the British in 1775 after many years of growing bitterness between the two. Enslaved people fought on both sides of the conflict, with many initially desirous of joining the British because of Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which stated that any enslaved person who fought for the British would be freed when the British (presumably) won. Ultimately, 3,000-5,000 Black people, both slave and free, fought for the Continental Army, while up to 20,000 fought for the British.

Fighting valiantly for the American side did not mean that slaves would be freed after the war, however. Despite numerous petitions to the new state governments from slaves who’d fought in the war, who both told the government of their contribution and pointedly called out the hypocrisy of keeping an enslaved population while touting the values of freedom, equality, and independence, there was no real effort by the states to end the system. Indeed, the Constitution, ratified in 1789, said little about slavery beyond calling for an end to the transatlantic slave trade by 1808. It also required states to return escaped slaves to the states from which they came and, most infamously, stated that 3/5 of the enslaved population could be counted for the purposes of attaining representation in the population-based House of Representatives.

While Northern and Mid-Atlantic states began to phase out slavery in the 1770s through the early 1800s, the institution not only remained in the Southern states, it grew tremendously.

The Antebellum Era: Enslavement and King Cotton

After the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the United States experienced a flowering of nationalism, as well as economic growth. Investments were made in transportation and communication, such as the railroad, steamboats and canals, and the telegram. The population spread inexorably westward, with new states added frequently to the Union while the fervor of “manifest destiny” swept the nation.

Slavery was perhaps even more integral to the country’s growth in this era than before the Revolution. With the explosion of cotton as an export crop (and the use of the cotton gin, which made harvesting the crop and preparing it for sale much easier), the South became extremely wealthy, and the North, in turn, benefited from its economic connections, whether it be in the textile, financial, or shipping industries, to the “Cotton Kingdom.”

By the eve of the Civil War, almost 4 million Black men, women, and children were held in bondage. While conditions varied from plantation to plantation and farm to farm, what all slaves had in common was the complete deprivation of any civil rights. They were not citizens and had no recourse to protest their enslavement. They were often denied the opportunity to learn to read or write and so could not communicate well. They were forbidden dogs, guns, houses, or property of their own, as well as freedom of movement, meaning they usually had to carry their “papers” or some form of permission from their owners if they left the property. Families were separated, women and girls were raped, and violence was an ever-present threat.

In his famous Autobiography published in 1845, Frederick Douglass wrote of the conditions of the slaves at one of the places he lived as a child: “There were no beds given the slaves, unless one coarse blanket be considered such, and none but the men and women had these. This, however, is not considered a very great privation. They find less difficulty from the want of beds, than from the want of time to sleep; for when their day’s work in the field is done, the most of them having their washing, mending, and cooking to do, and having few or none of the ordinary facilities for doing either of these, very many of their sleeping hours are consumed in preparing for the field the coming day; and when this is done, old and young, male and female, married and single, drop down side by side, on one common bed,—the cold, damp floor,—each covering himself or herself with their miserable blankets; and here they sleep till they are summoned to the field by the driver’s horn.”

Growing Calls for Abolition

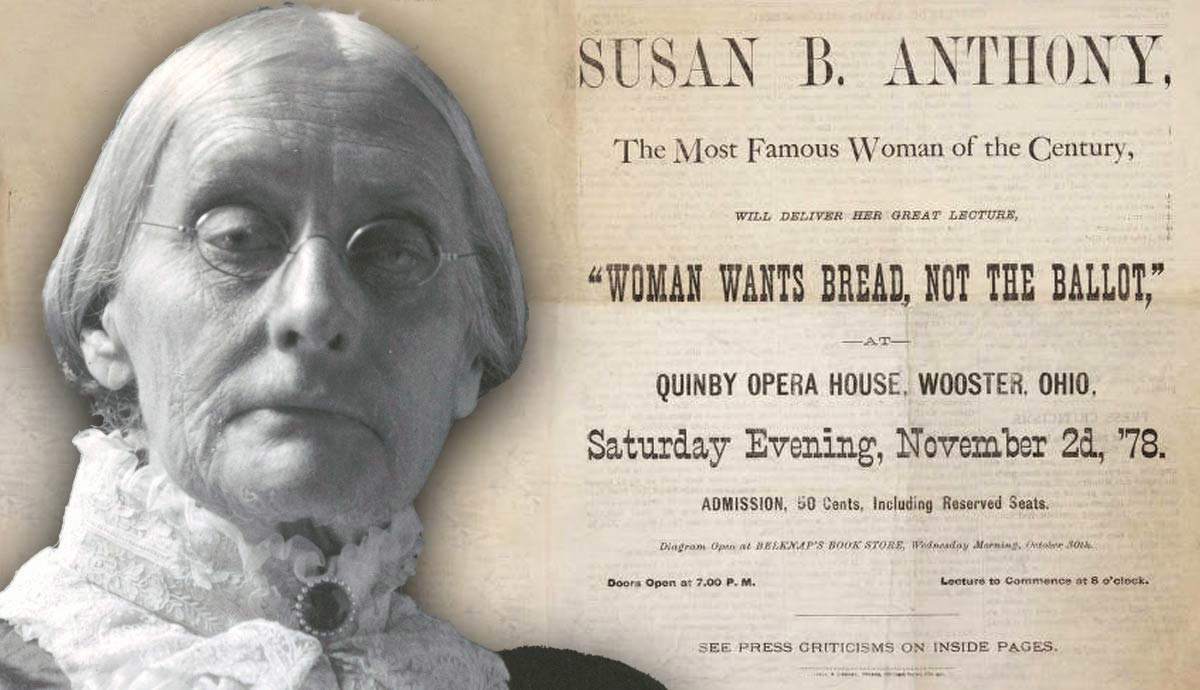

Douglass’s Autobiography was one of the most important slave narratives, works primarily written by escaped slaves to tell their stories and, in many cases, bolster the abolitionist cause. Abolitionism was the movement to eradicate slavery in the states and territories, and though there were some abolitionist groups as early as the late 18th century, a formal movement did not arise until the antebellum era. Both white and Black abolitionists worked to raise awareness of the truly horrendous conditions of slavery, hoping politicians would act. They distributed pamphlets, gave speeches, published newspapers, wrote books, poems, and essays, and lobbied politicians.

The abolitionists certainly were not popular, especially initially, as they were considered rabble-rousers (such as William Lloyd Garrison burning a copy of the Constitution, which he said was corrupt from its inception), unseemly (for example, women like Sarah and Angelina Grimké giving public speeches), and lawless (as seen with escaped slaves like Douglass who wrote and agitated from their safer positions in the North). However, they persisted in their bravery and boldness, calling for a decisive end to the scourge of slavery.

Angelina Grimké called upon the North to “cast out first the spirit of slavery from your own hearts, and then lend your aid to convert the South. Each one present has a work to do, be his or her situation what it may, however limited their means, or insignificant their supposed influence. The great men of this country will not do this work; the church will never do it,” seeing the real potential for change in ordinary men and women.

In harsher terms, Douglass, in his now-famous speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” given in 1852, put in stark terms what slavery had done to the country: “Fellow-citizens!…The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad; it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing, and a by word to a mocking earth. It is the antagonistic force in your government, the only thing that seriously disturbs and endangers your Union. It fetters your progress; it is the enemy of improvement, the deadly foe of education; it fosters pride; it breeds insolence; it promotes vice; it shelters crime; it is a curse to the earth that supports it; and yet, you cling to it, as if it were the sheet anchor of all your hopes. Oh! be warned!”

The Road to Civil War

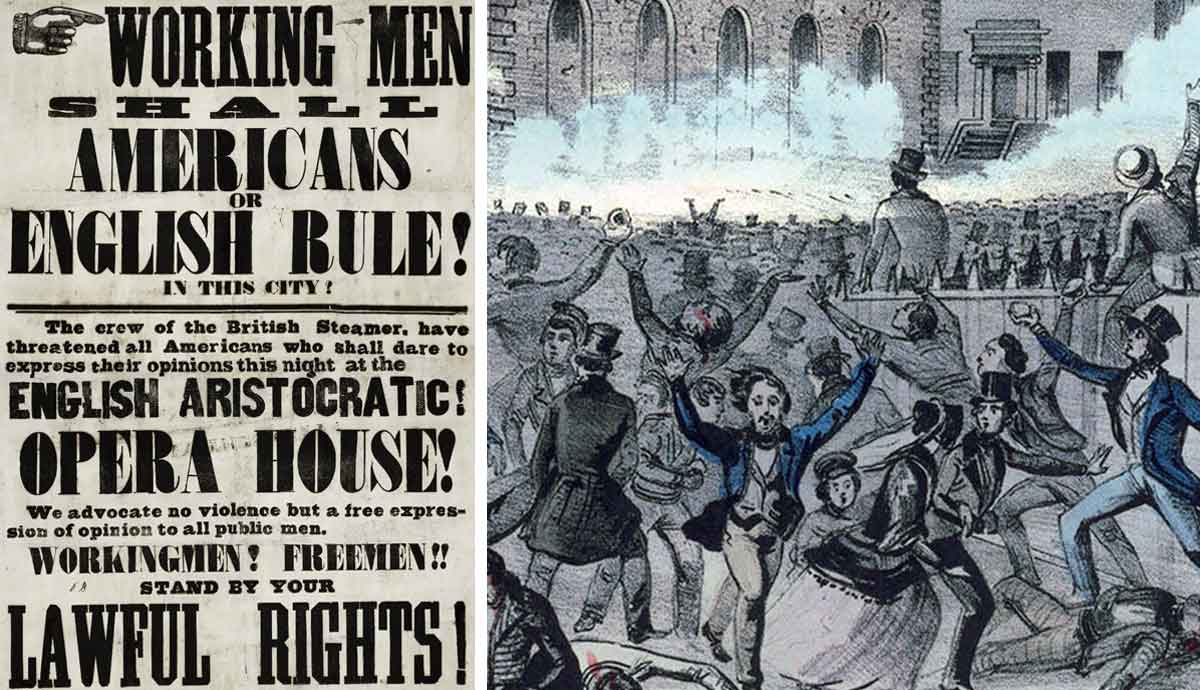

It is impossible to recount the myriad of events that ultimately led to the Civil War, but essentially, conflicts over slavery became increasingly inflamed and irreconcilable. Territorial expansion, such as the land gained after going to war with Mexico in 1846-1848, led to complicated questions about whether or not slavery would be permitted in the new areas. In some places, such as Kansas and Nebraska, the choice to allow the people to decide if they wanted slavery or not (“popular sovereignty”) proved not to be a panacea but instead an instigator of violence and corruption.

The South became more and more frustrated with fugitives escaping via the Underground Railroad, and even though one of the components of the Compromise of 1850 was a harsher Fugitive Slave Act, the North’s reluctance to adhere to it with any real conviction infuriated them.

Abolitionist agitation increased, sometimes becoming violent, as with John Brown and his followers raiding Harpers Ferry, a federal arsenal in Virginia, in an attempt to foment a slave uprising. Though a failure that ended with Brown’s hanging for treason, he was lionized among Northerners, showing just how far apart the regions were growing.

By the 1850s, the federal government was fractured after years of unresolved conflict. Congress was divided, President James Buchanan was pro-slavery, and the Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857 that Black people were not citizens and that Congress had no ability to legislate slavery’s presence or absence in the country.

The election of 1860 was one of the most fractured in American history, with four major candidates. The Democratic party split and ran two candidates as Northern Democrats and Southern Democrats. A pro-slavery party called the Constitutional Union Party had also formed, while the newly formed Republican party ran Abraham Lincoln, a relatively inexperienced politician from Illinois who had recently said that “a house divided against itself cannot stand” in a debate to win an open Illinois Senate seat. Slavery was inarguably on the ballot, with each of the four candidates espousing some proposal to either limit slavery’s spread or promote it even further.

The Civil War and the End of Slavery

With Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, many of the Southern states, led by South Carolina, decided to secede from the union. They formed the Confederate States of America, established a capital at Richmond, Virginia, and put Jefferson Davis in charge. In his First Inaugural Address to the divided nation, Lincoln stated he would not make war on the seceded states and called for the “better angels of our natures” to prevail. Not an abolitionist, Lincoln also said he would not go after slavery where it was already present. But Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter in 1861, initiating a devastating war that would not end until 1865.

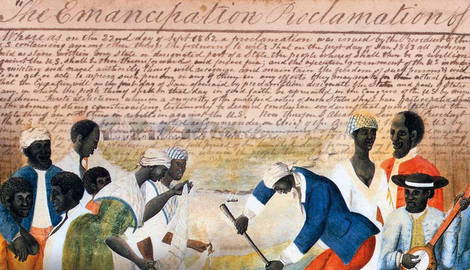

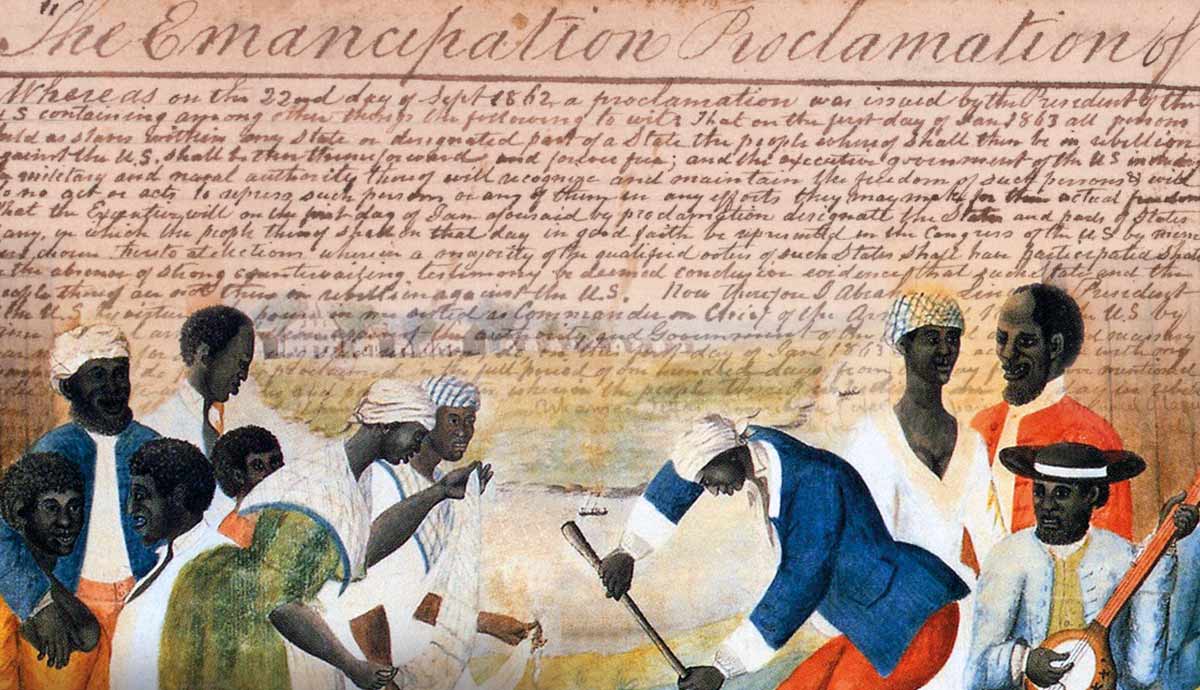

The Union did not fare well in the early years of the war, so even though Lincoln eventually did decide he needed to emancipate the slaves, he waited to do so from a position of relative strength. After a victory at Antietam in 1862, he drafted the Proclamation, which was officially announced on January 1st, 1863. All of the slaves in the states in rebellion—exempting those in the border states, which Lincoln hoped not to tip over into the Confederacy—were “then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.”

The Emancipation Proclamation was tremendously important in its explicit shifting of the war’s aim from solely preserving the Union to also eradicating slavery. While it could not easily be enforced while the war was ongoing, enslaved people who heard about it were overjoyed, many of them fleeing their place of bondage and others even joining the war effort. The National Archives explains how crucial Black participation in the war effort was: “By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well…There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman…, who scouted for the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers.”

After the turning points of Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, Lincoln and the Republicans in Congress started to look ahead to what the postwar world would look like. The Emancipation Proclamation lacked the weight of constitutionality, so Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment in January of 1865, and it was ratified by December of that year. The language stated that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The monstrous institution of slavery was ended. Now came the monumental task of Reconstruction, of integrating former slaves into the economic, political, and social fabric of the nation—a task that is still, generations later, ongoing.