By the time Hitler was 30, his life had led him in many different directions. From an aspiring artist to being poverty stricken and living on the streets of Vienna, his had been a life of hardship.

During the First World War, his fortunes changed, and he made a name for himself as a capable soldier. The end of the war and Germany’s defeat churned political unrest in the nation and set the stage for a dynamic that would thrust an unknown but passionate and angry man into his first position of power.

A succession of events led to the perfect storm for Hitler and the rise of Nazism. In July 1919, in the city of Munich, Hitler took his first step in the direction that would catapult him to power.

Hitler’s Rise in the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP)

Before the Nazi party was known as such, it was called the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the German Workers’ Party). It was created in January 1919 by a man named Anton Drexler, and the party mirrored his views of German nationalism, anti-Marxism, racial superiority of the German race, anti-Semitism, and anger over the treatment of Germany during the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I and imposed harsh penalties on Germany.

Although a small organization at the time, comprising around 60 members, the DAP was viewed with suspicion and marked for infiltration by the German authorities. Adolf Hitler, a Gefreiter (corporal) who had stayed in the military after the end of the First World War, was tasked with the job of spying on this group of nationalists.

Hitler was not impressed at first. A staunch disciplinarian, Hitler viewed the DAP meetings as disorganized and amateurish. He did, however, enjoy engaging in political discussions with its members. He listened to the speeches and abandoned his task as an infiltrator, instead joining the DAP.

On September 12, Hitler was involved in a heated argument over the political direction Bavaria should take. Anton Drexler was impressed with Hitler’s oratorial skills and urged him to join the DAP. Hitler accepted. Despite his idea of creating his own party, Hitler realized that he could rise in prominence within the DAP, which was still a very small organization, and steer it in the direction he wanted it to go.

Hitler made his first speech on October 16, 1919. This (arguably) marked the beginning of his rise to power. His words encapsulated the audience, and Anton Drexler was impressed even further. Hitler became the chief of propaganda for the small party in early 1920, and through his efforts to promote the party, the DAP grew considerably, attracting thousands of new members.

Hitler gave the party clear purpose and solidified its strategy and policies. Included in these policies was a desire to exclude Jews from German citizenship, among other things. This would be the first step in a succession of events that would eventually lead to the Holocaust.

Although a DAP manifesto had already been drawn up, it was Hitler who brought it to the forefront and kickstarted the aggressive pursuit of the 25 points contained therein. The party began to clearly show its character as being anti-Marxist, anti-Semitic, anti-capitalist, anti-democratic, and anti-liberal. Hitler also designed the Nazi swastika flag, giving the party a striking image to make it easily identifiable.

The party’s executive committee, however, realized that a large proportion of struggling workers and middle-class Germans leaned to the left of the political spectrum. To appeal to these people, the committee decided to change the party’s name by adding the word “socialist” to the title. But to differentiate it from the socialist movement, which was certainly not nationalist, the word “nationalist” was also added. This move was designed to attract members from across the political spectrum who had little knowledge of the intricacies of political ideologies. Thus, the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei became the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or simply the Nazi Party.

Almost immediately, the anti-Jewish sentiment was acted upon. Only racially pure Aryans were allowed into the party, and those with non-Aryan spouses were banned.

Hitler’s move to become the chairman of the Nazi Party was the result of a mutiny. Members of the Executive Committee attempted to force the Nazi Party to merge with a rival party, the German Socialist Party. For Hitler, this was an act of betrayal of the Nazi Party’s principles. He tendered his resignation, and the Executive Committee realized that without their greatest orator, and the face of the party, the Nazi Party would face certain abandonment.

They acquiesced to the hardliners within the movement, and Hitler was inaugurated as the chairman, replacing Anton Drexler as the head of the party. Hitler then had the Executive Committee dissolved and gained full control of the party, suppressing and ousting his political rivals from within its ranks.

It was around this time that Hitler received the moniker of Führer, and the party founded the Sturmabteilung (Storm Division, SA), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, which began to engage violently with its enemies.

The SA grew significantly in strength during the early 1920s as the Weimar Republic grew weak, and disenchanted World War I veterans flocked to the Nazi party, seeing in Adolf Hitler a person with whom they could relate. Following the successful creation of the SA, the Hitler Youth was then created for the children of Nazi Party members.

Rallies were held regularly, and beer halls formed popular venues. The promise of free beer went a long way to helping the party grow its membership base. The party expanded beyond Munich and Bavaria, finding popularity in other parts of Germany as well. It started printing its own magazine, Der Stürmer, and acquired a newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter. Around this time, prominent future Nazi members Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Goering joined the party.

The Beer Hall Putsch

By 1923, Germany was in a state of chaos. The Treaty of Versailles forced Germany into reparations that it could ill afford, and its industrial heartland of the Ruhr Valley was under French occupation. The Weimar Republic in Germany was the country’s first attempt at a democracy, and it was weak, having gone through several chancellors and cabinets.

Inflation was rife, and the German Mark became worthless. Food shortages became common, and people resorted to bartering. Revolutionary movements took to the streets in open rebellion, threatening the German government from the extreme left and right of the political spectrum.

Hitler chose this moment to launch a coup against the German government. His plan was to force three powerful men, Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow, and Hans Ritter von Seisser, to join him. They were the state commissioner, an influential army general, and the Bavarian State Police Chief, respectively. When the three met at the Bürgerbräukeller for a speech event, Hitler launched his plan.

With several hundred Nazis, he surrounded the venue and at gunpoint, forced the three men to support his coup. The three men agreed to join Hitler, but the next day Seisser and Lossow reneged on their word and planned to resist Hitler’s march through the streets.

The march was a disaster. Almost immediately, as Ernst Röhm and his SA began their march, they were met by the police and forced to retreat. The other elements of the Nazi march fared no better, and clashes with the police led to 16 Nazis and four policemen losing their lives. Hitler was arrested two days later and charged with treason.

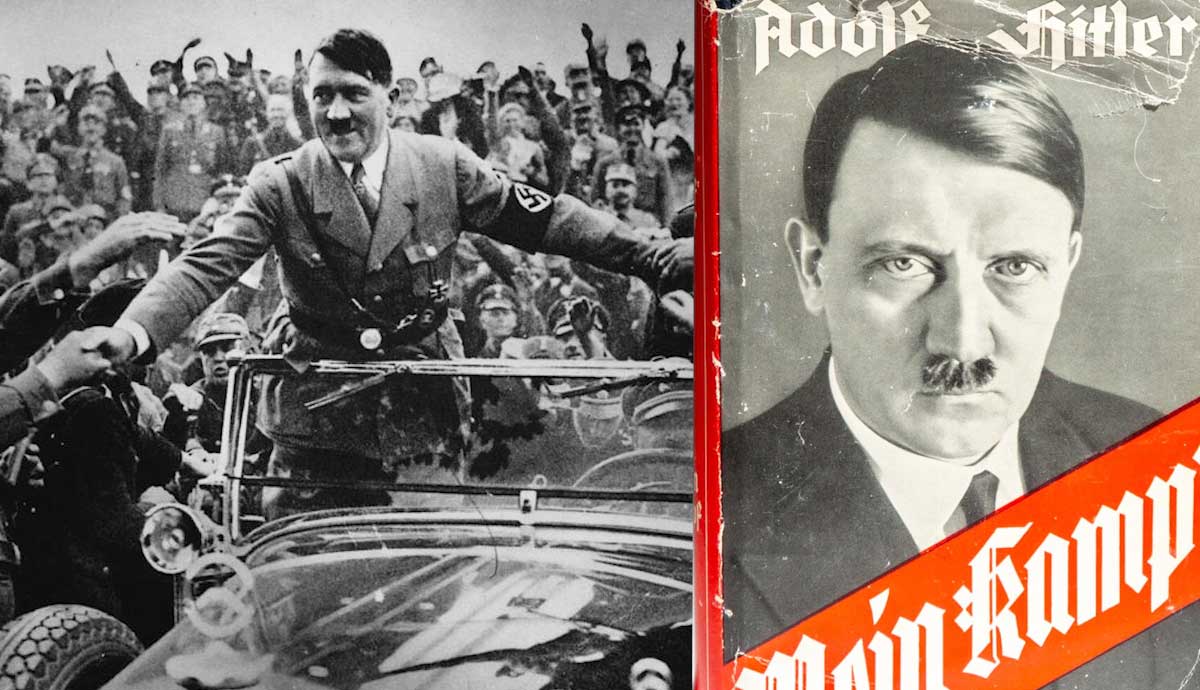

Hitler’s trial began on February 24, 1924. He denied the charge of treason, arguing that he was only trying to restore order to Germany. The judges were sympathetic to his cause and gave him the light sentence of five years in Landsberg Prison. He would serve only nine months, during which time he wrote Mein Kampf.

The Nazi Party Wanes in Popularity

After Hitler was imprisoned, the Nazi Party was banned. Its new leader, Alfred Rosenberg, also lacked the charisma that Hitler had, and membership of the party dropped significantly. To add to this dynamic, the German economy started to recover, thus leading people away from revolutionary ideas such as Nazism, as there seemed little need to put faith in an entity suggesting radical change.

In 1925, after his release from Landsberg Prison, Hitler took over the leadership of the Nazi Party again and convinced the authorities to lift the ban. He saw the need for a restructuring of the party, and in 1926, he convened the Bamberg Conference, which sought to deal with problematic issues. One of these issues was dissent among the northernmost branches of the Nazi Party. Hitler sought to cement centralized control and exert more authority over the organization.

The first democratic national election to be contested by the Nazi Party was in 1928, in which the Nazi Party scored just 2.63% of the total vote. It was clear that the country was back on track to economic prosperity, especially with generous loans from the United States boosting the German government coffers.

The economic progress, however, all came to an abrupt end in October 1929 when the Wall Street Crash sent shockwaves around the world, plunging Germany into another economic meltdown. This was exactly the situation the Nazi Party needed to once again become the powerful organization that could succeed in winning over the German people.

The Nazis in the Reichstag

From 1929 to 1933, the Nazi Party grew to become the biggest party in Germany, but there were challenges in that it could not win a clear majority in the Reichstag.

The economic collapse brought a huge influx of support to the Nazi Party as people became desperate again for change. Farmers, having a difficult time before the crash, suffered even more as food prices plummeted, while factories were forced to lay off workers. Unemployment skyrocketed.

The German working classes, in their plight, were eager to look for reasons for their suffering, and the Nazis offered plenty of answers. With Hitler’s anti-Semitic, anti-democratic, and anti-Marxist rhetoric, he began to reshape the ideological structure of Germany, radicalizing many with hatred and anger at the Jews and the Weimar Republic. This hatred also extended to France and the Treaty of Versailles, which had effectively neutered Germany’s ability to recover economically and militarily. Hitler presented nationalist pride and stoked the fires of German revival based on racial lines.

In the Reichstag, Heinrich Brüning of the Centre Party had been appointed by President Paul Von Hindenburg to be Chancellor. Brüning’s party, however, did not have a majority, and he had to govern using Article 48, which allowed the chancellor to pass emergency measures without needing parliamentary support. As the government was a minority, and Article 48 was being used too frequently, the Reichstag quickly turned against the government and voted it down until it collapsed. Von Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag, allowing Brüning to stay in office.

By the next election, in September 1930, the Nazi Party increased its share of the vote to 18.25% amid a failure of the Weimar government to stabilize the situation. Successive Weimar attempts in forming new governments fell flat, and the people increasingly looked for more radical solutions in governing Germany.

On the far-right, people flocked to support the Nazis, but the economic woes also fed the Nazi’s biggest enemy, the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (German Communist Party, KPD). As the leading Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany, SPD) struggled to maintain its grasp on power, the Nazis and the communists began fighting for future control over all of Germany.

This struggle didn’t just take place in the Reichstag. It happened on the streets as well. The Strurmabteiling was used to protect Nazi meetings and rallies as well as to disrupt the congregations of other parties, especially that of the Communist Party, which had its own militia called the Roter Frontkämpferbund (Red Front Fighters, RFB). These two militias regularly clashed, resulting in injury and death.

In 1932, a presidential election turned out to be a three-way race between Hindenburg, Hitler, and communist leader Ernst Thälmann. Hindenburg narrowly won, but the popularity of Hitler had been markedly improving. Later that year, Brüning lost the support of Hindenburg, who appointed Franz von Papen as the new chancellor. This act triggered a call for a general election.

The 1932 general election catapulted the Nazis into power in the Reichstag. With 37.27% of the vote, they became the biggest party in the Reichstag. Despite this, they lacked a clear majority, and the situation would evolve into one that was difficult to navigate for everybody involved. Hitler demanded the chancellorship, but Von Papen refused to step down. Instead, he and Hindenburg decided to manipulate the situation in order to defeat Hitler and the Nazis.

Von Papen dissolved the Reichstag, hoping it would strip the Nazis of their political power. An election in November 1932 showed the Nazis lost a small percentage of votes, but they still controlled the majority of the Reichstag seats. Von Papen then tried to convince Hindenburg to dissolve the entire Weimar constitution. The Minister of Defence, Kurt von Schleicher, opposed this action, persuading Hindenburg that doing so would lead to a civil war.

Hindenburg responded to Von Papen by sacking him and replacing him with Von Schleicher. Von Papen, however, was desperate to regain power, and he convinced Hindenburg that if he made Hitler chancellor with Von Papen as vice chancellor, he would be able to control the Nazi leader. Hindenburg relented and swore Hitler in as chancellor.

Von Papen proved to be very wrong about being able to control Germany’s newest chancellor.

Hitler’s rise to power was a unique series of events born from weak opposition to his intense and passionate drive to grasp power. His most alarming legacy, however, was yet to be written.