The Victorian dead body trade was a key part of the development of anatomy and medicine in the 19th and 20th century, without which a lot of the achievements made today would not have been possible. The history behind the trade, however, is dark and complex. The demand for bodies grew and grew and as a result the dead body trade became, not only more sophisticated, but more dangerous.

Who Wanted Bodies and Why?

Due to the avid pursuit of progress in the 19th century, anatomists and surgeons wanted more bodies to advance their research. The Murder Act of 1752 had allowed anatomy schools to use the dead bodies of criminals charged with murder, but these were small in number. On average, this was around ten bodies a year from the courts, but private medical schools had no legal source. [1]

Demand was further increased with the 1858 Medical Act which stipulated that all medical students had to study human anatomy for two years before they were granted a license to practice medicine or surgery. Further, the 1885 Medical Act required all doctors to qualify in both medicine and surgery. [2] By the later nineteenth century, student numbers continued to expand and so did the demand for dead bodies.

What Impact Did the 1832 Anatomy Act Have?

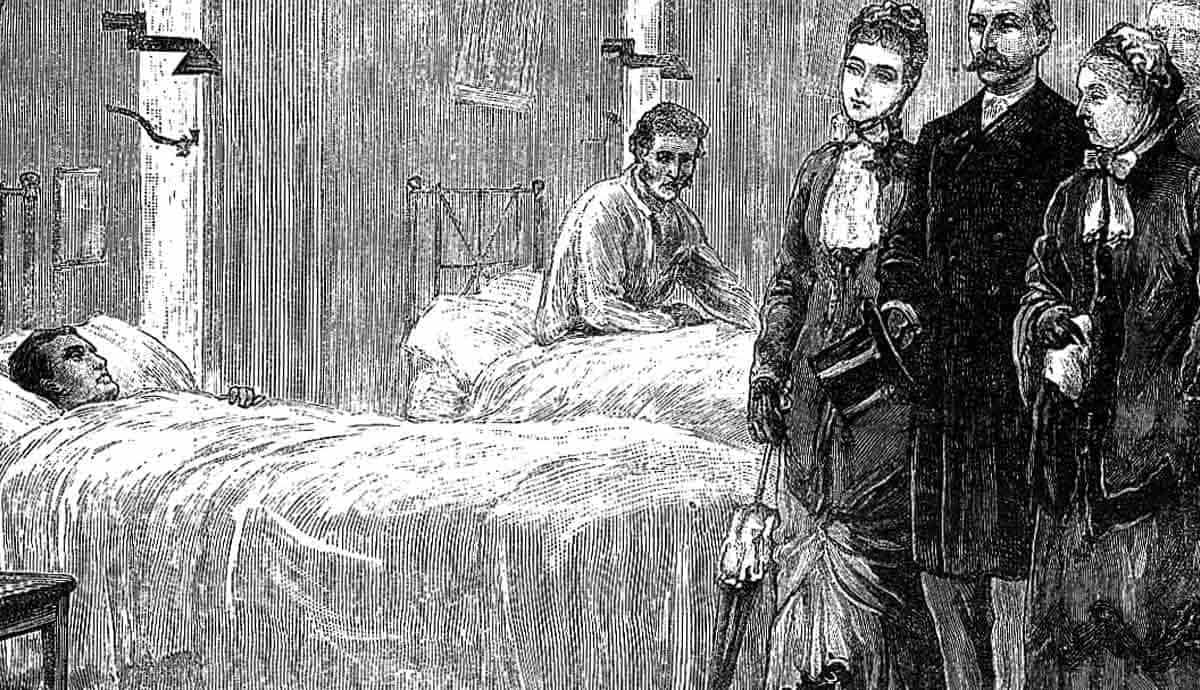

Due to the limited supply of bodies, individuals turned to body snatching (digging up graves) and selling them—these people became known as resurrectionists. The infamous William Burke and William Hare even took body dealing a step further in 1828 by murdering 16 people in Edinburgh and selling the bodies.

In the hopes of putting an end to body snatching, the Anatomy Act was passed in August 1832, ending the use of dissection as a punishment for murder and allowing unclaimed bodies from public institutions to be used instead. This meant the poor became a target as, for example, if they died in a workhouse, their body could be taken and sold as, prior to 1844, no law prohibited the sale of bodies to medical schools.

The Act changed what bodies could be acquired and how but did not solve the shortage. The trade became more sophisticated and more complex as the demand for bodies continued to grow- the pace of the trade quickened, and supply chains were set up involving a number of different people, from anatomists to body dealers. At the peak of teaching cycles, a 72-hour turnover of bodies was typical, body dealers had to be fast in acquiring bodies and fast in selling them. [3]

How Were Bodies Acquired?

Bodies were acquired in a number of ways-both legal and illegal-even body snatching remained despite attempts to end it. A key customer in the trade was St. Bartholomew’s Hospital which worked with coroners, parish officials and workhouse officials to obtain bodies. Large wicker baskets were even left inside the hospital’s gates for passing body dealers to fill up- this included the bodies of the destitute who died outside the hospital. [4]

Schools also offered deals to parish officials to provide workhouse inmates with free hospital treatments in exchange for corpses from dead houses. Further, coroner’s costs could be recovered by selling on bodies after a standard inquest, especially intact corpses.

The workhouse was one of the most important sources of dead bodies and the relationship with medical schools proved lucrative. In 1858 a scandal came to light involving the St. Mary Newington workhouse where the master Alfred Feist had been working with the parish undertaker, Robert Hogg, to supply bodies to Guys Hospital Medical School instead of burying them as requested.[5]

How Were Bodies Transported Across the Country?

Growing demand made it necessary to go further afield to acquire bodies. Alexander Macalister, Professor of Anatomy at Cambridge University in 1883, set up a system involving the railway that a number of regional medical schools copied. Attached to the rear carriages of the trains were ‘funeral wagons’ which contained boxes with the bodies inside, carefully sealed to prevent any smells escaping. A train like this left Liverpool Street Station in London, travelling via Cambridge and Doncaster three times a week- this became known as the ‘dead train’. [6]

Oxford University’s human anatomy teacher, Arthur Thomson, adopted this process in 1885 using the railway to acquire bodies from places like Leicester, Reading and Staffordshire. The dead body trade proved to be lucrative for many, but this often came at the cost of everyday people, especially the poor. The Victorian dead body trade was undoubtedly unethical and complex, but it proved vital to the expansion and growth of medicine and anatomy in Britain.

Sources:

[1] Pond, Elizabeth F. “Dissection: a Fate Worse Than Death.” Journal of the Royal Medical Society 21 (2013)

[2] Hurren, Elizabeth. “Whose Body Is It Anyway? Trading the Dead Poor, Coroner’s Disputes, and the Business of Anatomy at Oxford University, 1885-1929.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82 (2008)

[3] Hurren, Elizabeth. Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and its Trade in the Dead Poor, c.1834-1929. Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

[4] Hurren, Elizabeth. Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and its Trade in the Dead Poor, c.1834-1929. Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

[5] MacDonald, Helen. Possessing the Dead: The Artful Science of Anatomy. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2010.

[6] Hurren, Elizabeth. Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and its Trade in the Dead Poor, c.1834-1929. Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012