Peronism, a populist movement and political ideology centered around three-term President Juan Perón, dominated Argentine politics in the 1940s and early 1950s. While Perón remained the ultimate authority, the actions of Perón’s controversial First Lady, Eva Perón, were pivotal in the development of his political movement. The country’s response to Evita, both positive and negative, would come to shape Peronism—which plays a central role in the country’s politics even today—in unexpected ways.

What Is Peronism?

At its start, Peronism was precisely what it sounds like—a political ideology centered around three-time Argentine president Juan Perón and his vision for the country in the 1940s. A form of populism, its primary tenets—aside from winning Perón the presidency—were staunch nationalism, economic independence, and the pursuit of social justice for the descamisados (shirtless ones), Argentina’s poor working class. Perón promoted a so-called “third way” that sought a middle ground between the West’s aggressive capitalism and the East’s controversial communism. This meant pursuing a balance between promoting private enterprise and implementing social programs to alleviate poverty.

In Perón’s own words, “Perónism is humanism in action; …in the social sphere, it is a theory which establishes a little equality among men, which grants them similar opportunities and assures them of a future so that in this land there may be no one who lacks what he needs for a living … in the economic sphere its aim is that every Argentine should pull his weight for the Argentines and that economic policy … should be replaced by a doctrine of social economy under which the distribution of our wealth … may be shared out fairly among all those who have contributed by their efforts to amass it.”

At its inception, Peronism garnered support from both the right and left. The right, including the military, supported its fervent nationalism and some of its more authoritarian impulses, like reigning in a free press; the left believed in its promises of alleviating poverty and shoring up workers’ rights. The result was a support base constantly at war with itself—and with dramatically different opinions of Perón’s secret weapon: Evita.

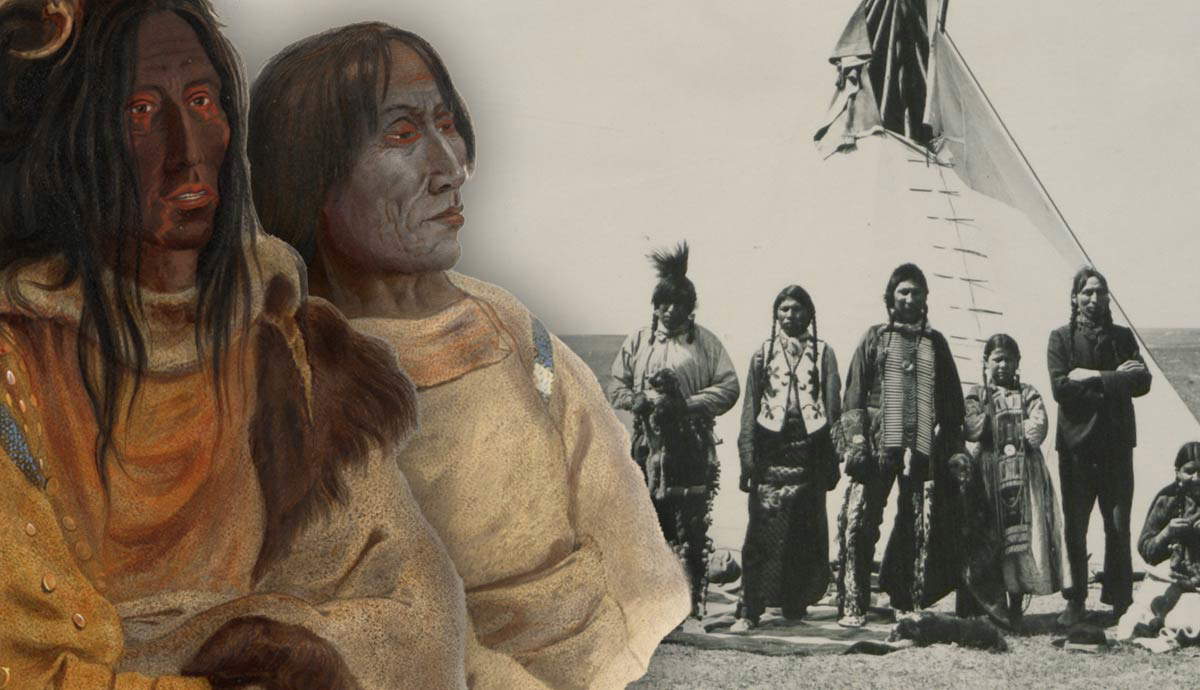

Evita and the Descamisados

Prior to winning the presidency, Perón was Argentina’s Minister of Labor. This position allowed him to earn the support of Argentina’s working class through pro-labor and pro-union legislation, ultimately propelling him to the top office. Like any populist movement, Peronism relied largely on a cult of personality—which shifted into overdrive when Perón met and married Eva Maria Duarte.

While Perón had won the support of his country’s descamisados as Labor Minister, his personal appeal to them was more limited. He had little in common with the nation’s poor working class, with a middle-class upbringing and a distinguished career in the military. Evita, on the other hand, had grown up in poverty. Her family was left nearly destitute after the death of her father, who had never married her mother. As a teenager, she moved to the capital to pursue an acting career, which ultimately led her to meet and quickly marry the future president.

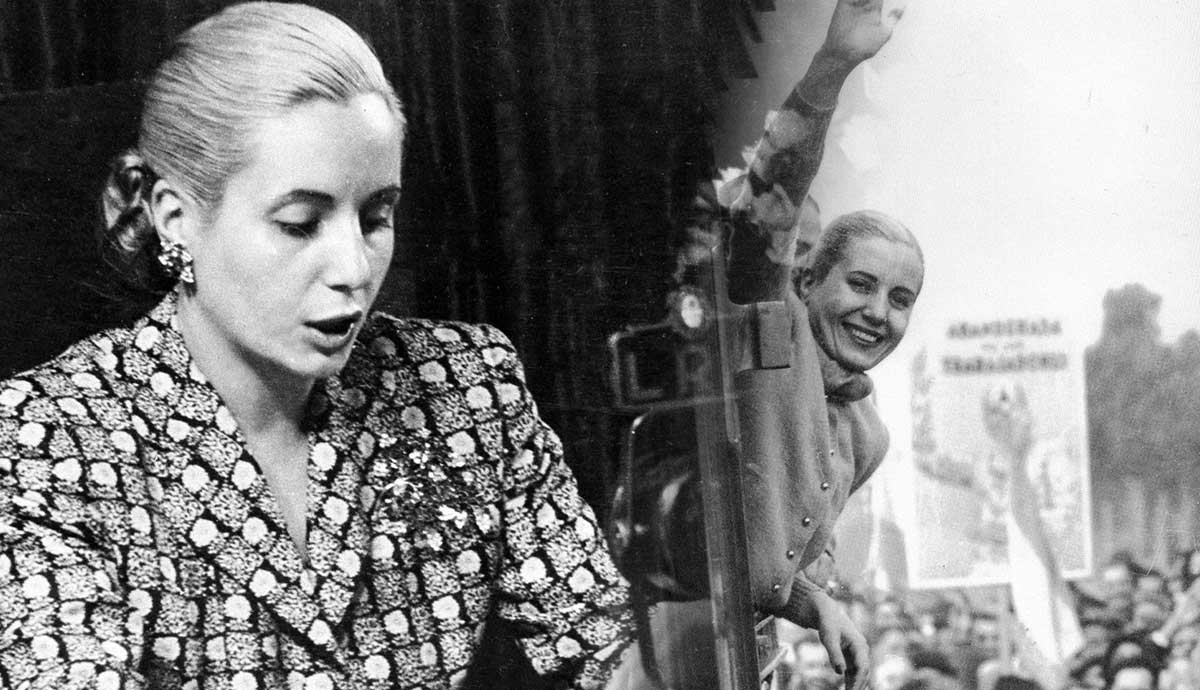

Evita’s rags-to-riches story inspired many Argentines, and her youth, beauty, and glamor also won many hearts. For her part, Evita left behind her acting career to serve as Perón’s mouthpiece. She reportedly had few political notions of her own but took Perón’s word as gospel and threw herself fully into promoting his agenda and policies. Ultimately, she took up an office in the Ministry of Labor and effectively ran the show.

Evita painted the struggle of the descamisados as a mutual one—she had shared their experience, knew the challenges they faced, and wanted to work with them to improve their lot collectively. While many politicians would generate cynicism with such an approach, Evita’s performance skills and background allowed her to deliver such a message with sincerity.

It was not words alone that won Evita her devoted followers, but her willingness to do the actual social justice work she was promising—going above and beyond Perón’s initial commitments to the working class. Her tireless devotion to social justice projects and her willingness to walk among the poor and the sick quickly developed into a near-worship of the First Lady and her saint-like persona. Rumored to have been prevented from taking the First Lady’s traditional position at the head of the Sociedad Beneficia de la Capital, the country’s leading social service organization, she created and took an active role in the Eva Perón Foundation to support the work of ministering to the poor. Her foundation became the driving force of social justice throughout the country: building schools and hospitals, sponsoring scholarships and youth sports, and delivering basic household necessities.

Poverty reduction wasn’t the country’s or government’s achievement; it was Evita’s—and her husband’s by association.

Women for Perón

Evita is often given credit for Argentina granting women the right to vote, but women’s suffrage was a cause Perón himself championed long before Evita joined the movement. There’s little evidence he was particularly concerned with women’s empowerment; he simply calculated that more working-class voters overall would lead to more votes for him. As researcher Mariano Plotkin suggested in Mañana es San Perón: A Cultural History of Perón’s Argentina, “Women would gain political rights because Perón needed women to bring his doctrine into the home.”

While Evita actively campaigned for the women’s suffrage law during Perón’s first term, scholars note that its passage was all but guaranteed due to the number of Congressional seats held by Peronists. Evita’s true role was in organizing Argentina’s women into not just a voting force but a force for Perón and Peronism.

While Evita encouraged women’s participation in the Partida Peronista Feminina (Women’s Peronist Party), of which she was president, the party engaged in very little activity that could be called political. It primarily functioned as an arm of the Eva Perón Foundation, with centers established in various neighborhoods to assist in implementing poverty reduction measures—essential work for ensuring the loyalty of Argentina’s working-class women.

Though political office was now open to women, Evita was adamant in her belief that a woman’s primary duty remained that of caregiver and wife, declaring, “The first objective of a feminine movement which wants to do good for women, which doesn’t aspire to change them into men, must be the home.”

Though personally she held a great deal of power, she emphasized her ultimate subjugation to her husband and his policies. The PPF’s political activity was largely limited to registering women with the party and encouraging them to vote for Perón in the 1951 election—as well as to spread Perón’s message in their homes.

Her efforts were a success. When women were first able to vote in the 1951 presidential election, over 90% of women eligible to vote did, with the result that Perón took 63.5 percent of the vote and his party won every Senate seat. The support of the country’s newly enfranchised working-class women was cemented. Moreover, Evita had tread a fine line and managed to shape Argentina’s women into a powerful voting force without encouraging them to pursue political activism or positions of power that the men of the era may have found threatening.

Antagonism: Evita vs. The World

While Evita won the adoration of Argentina’s poor, especially the women, nearly every other faction in the country was against her. The elites viewed her as a crass social climber. The military, unhappy with Perón’s taking up with an actress from the start, felt she had far too much power and influence. Businessmen grew resentful of the “voluntary” contributions that were demanded for her foundation.

Most scholars argue that the feeling was mutual, many attributing it to her resentment that she was never accepted by the social and political world into which she had risen. Others suggest that having been elevated to her powerful position by the descamisados, her loyalty to them demanded her opposition to the forces that had traditionally kept them in poverty. This included the Catholic Church; though she did not publicly condemn their close relations with the nation’s oligarchy during her lifetime, a memoir, albeit of dubious origins, finally published in 1987, criticizes them for showing “coldness and indifference” to the poor.

Though in its infancy, the Peronist movement sought a balanced approach to navigating the nation’s class divide so as not to alienate either side, Evita’s fiery rhetoric often and increasingly juxtaposed the “us” of the descamisados” with the “them” of the nation’s elite—which ultimately included anyone who wasn’t unwaveringly loyal to herself and Perón. While this approach consolidated support for Perón among the working class, it had the opposite effect among the military, businessmen, and landowners.

Perón, too, took a harsh stance against perceived enemies, though his ire was generally directed toward the press and opposition political movements. Eva’s own devotion to Perón was unwavering, and loyalty became an overarching theme as the administration progressed, dovetailing neatly with Peronism’s nationalist rhetoric—loyalty to the Peróns became equated with loyalty to Argentina itself.

Evita’s Death: Peronism at a Crossroads

Though her beloved descamisados had pushed for her to take on the vice presidency for Perón’s second term, she declined, whether due to Perón’s opposition or her own ill health. As her condition worsened, she was no longer physically able to orchestrate her social justice programs, but her descamisados never lost faith—and Evita transformed from saint to martyr. She arguably became more militant in her support of Perón and her opposition to virtually everyone else as her health failed. She died of cervical cancer on July 26, 1952, just months after Perón was inaugurated for his second term.

Even in death, Evita continued to shape the path of Peronism. Her passing marked a turning point for the country and for Perón himself. He was now without the influential First Lady who had shaped much of his first term and won his administration unwavering support from the country’s large working class. He was also facing increasing economic difficulties caused, in part, by the social spending she had championed.

Perón and Peronism were at a crossroads—would he recommit to pursuing his “third way,” working to balance the various factions seeking to influence his administration in his wife’s absence, or continue to rail against his perceived enemies while emptying the state coffers on social programs to retain Argentina’s working class?

Evidence suggests that while Perón still enjoyed a great deal of the support he and Evita had won from the nation’s working class, the descamisados’ loyalty began to falter with her passing. More importantly, forces once ambivalent about his administration grew increasingly opposed to Perón’s authoritarian tactics and perceived economic mismanagement. The military he had long relied on as allies became disenchanted with his leadership as he increasingly purged disloyal members. He also decided to pick a fight with the Catholic Church, which had once supported his movement. And all the while, outward pressure against the regime, particularly from the United States, grew.

Legacy: Peronism Without the Peróns

Perón was ousted in a military coup in 1955, and he fled first to Paraguay and then Spain. At this point, the military made a crucial mistake: they tried to pretend the Peróns never existed. The Peronist party was banned, any pro-Perón material was censored, and even Evita’s corpse was stolen. But since the masses had largely still supported Perón when he was deposed, all of this served to reinforce the idea of Perón as the victim in the company of his martyred wife, Evita.

Peronism didn’t die then, nor has it since. While Argentina floundered through a series of military juntas and short-lived civilian governments in the decades after Perón, the only political party capable of forming a government with any measure of popular support was banned. This widespread belief, begrudging among many factions, that only Perón could unify the country led to his return in 1973. He died during his brief third term, making way for yet another military coup against his third wife, Isabel, who took charge in his absence.

But a belief in (at least some of) the Peronist ideals persisted, as well as a near-worship of Evita in some communities. Despite Peronists being one of the primary targets in the country’s Dirty War, when democracy finally returned in 1983, the Peronist party—technically the Justicialist Party—remained an influential political player. Peronist presidents since then have included Carlos Menem, Eduardo Duhalde, Néstor Kirchner, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and Alberto Fernández, with the party consistently winning substantial representation in Congress. Each of these subsequent Peronist presidents has shaped the party in their own way, pulling it further right or left and ultimately resulting in rival factions within the party, accusing the other of betraying the ideals of Peronism.

Peronism lost big in 2023 to right-wing newcomer Javier Milei, and many have blamed the surprising defeat on Peronism losing its way, lacking both sound leadership and political direction. While its support base has always remained the working class that Evita charmed decades ago, perhaps her greatest legacy within Peronism is its self-destructive internal divisions.