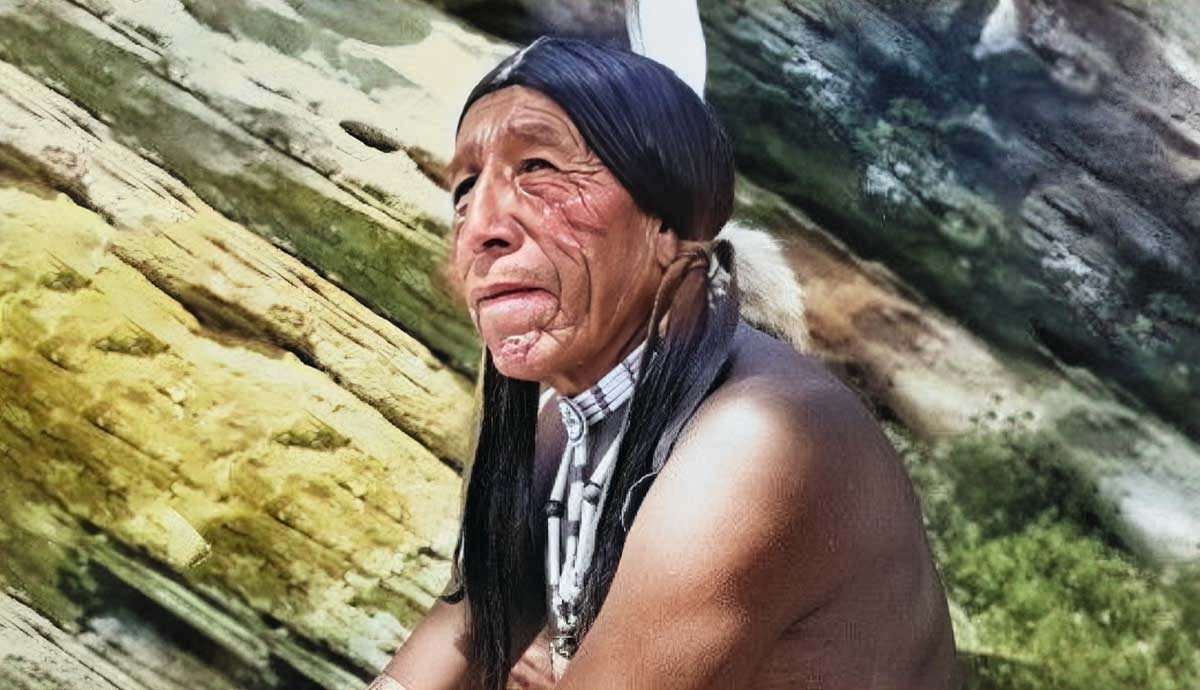

In the 1950s and 1960s, Ben Black Elk became a familiar presence among summer tourists at Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Upon his death aged 74, the New York Times published a brief obituary referring to him as the “Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore.” Additionally, he was recognized as the most photographed Indian in the world. Revered as a respected elder, tribal historian, and ambassador for the Lakota people, Ben Black Elk approached his unofficial role as “unofficial greater” at Mount Rushmore with utmost dedication. He maintained this association for over 27 years.

Who Was Ben Black Elk?

Benjamin “Ben” Black Elk (1899-1973), who came to be known as the Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore, was held in high esteem as a historian of the Lakota and an educational activist. He first came to prominence as a translator for his father in the recording of Black Elk Speaks (1932). The American ethnologist John Neihardt’s interviews with Lakota holy man Nicholas Black Elk – mediated by Ben – came to play a significant role in the transmission and preservation of Lakota history, folklore, and myth.

Following his father’s death in 1950, Ben Black Elk carried forward his legacy by imparting the teachings and narratives of Lakota spirituality and culture that had passed to him. His enduring presence at Mount Rushmore during the 1950s and 1960s, where he served as an “unofficial greeter,” earned him the title of “The Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore.”

The Most Photographed Indian in the World

Following in the footsteps of his father, who entertained tourists in the Black Hills in the 1930s and 1940s, Ben Black began spending most of his summers at Mount Rushmore in the early 1950s. Clad in traditional Lakota attire, he posed for countless photographs and engaged visitors from all over America and the world, sharing stories that celebrated the history and cultural heritage of the Lakota, but also asserted the Lakota as a people that lived in the present.

On particularly busy days, it is said that he could be photographed thousands of times. Postcards featuring his likeness against the backdrop of Mount Rushmore became ubiquitous in gift shops across the United States. Ben Black Elk’s impact on tourism in South Dakota led to the establishment of the Ben Black Elk Award in 1979. An annual accolade that honors the achievements of individuals, organizations, and communities in the field of South Dakota tourism.

Mount Rushmore and the Lakota

The history of the Lakota in the Black Hills of South Dakota is, according to Lakota folklore, as old as the hills themselves. Among these sacred hills lies Mount Rushmore, known to the Lakota as the Six Grandfathers. The Six Grandfathers holds profound significance as sacred land and an integral part of Lakota cultural heritage. Despite legal ownership of the Black Hills as stipulated by the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), the United States seized the hills after gold was discovered in 1874.

In the early 1920s, South Dakota State Historian, Doane Robinson conceived of the idea of a colossal sculpture in the Black Hills to draw tourists to the region. By the end of the decade, President Calvin Coolidge had dedicated the national monument of the four presidents (1927). The mountain itself was officially renamed Mount Rushmore in 1930. However, to the majority of the Lakota Sioux, Mount Rushmore represents the theft and desecration of their sacred land. Some advocate for its removal.

Preserving Lakota Culture

Ben Black Elk dedicated more than 27 years of his life to sharing the wisdom and traditions of the Lakota people with Mount Rushmore tourists. His sheer presence, not to mention the countless photographs and postcards distributed worldwide attest to his impact. His relative fame as the “Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore” provided a platform for his advocacy of Native American rights and preservation of Lakota heritage. He became a sought-after speaker at educational institutions and civic organizations, testified before the US Senate hearing on Indian education (1968), and also landed himself an uncredited role in the Hollywood epic How The West Was Won (1962).

Ben Black Elk once revealed that near the end of his father’s life, they often lamented the loss of the old Lakota ways. While Ben may not have achieved the same level of recognition as his father, his role as the Fifth Face of Mount Rushmore played a modest, but significant role in the promotion and preservation of Lakota culture.