Referencing the period between 1871 to 1914, La Belle Époque literally means “the beautiful era” in French. In more ways than one, La Belle Époque has been regarded as Europe’s golden age, a remarkable time that significantly altered the history of the continent and beyond. In less than fifty years, Europe witnessed vast developments on the political, socio-economic, cultural, and technological fronts. While generally heralded as a transformative era, La Belle Époque was a term that only came into popular use much later. When examined through the lens of nostalgia, hindsight, and retrospection, it begs the question of whether the era was truly romantic, or was it merely romanticized?

La Belle Époque Illuminated in the City of Light

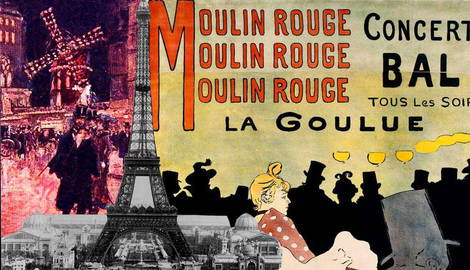

At the heart of the entire La Belle Époque spectacle was Paris, a city giddy with the unparalleled prosperity and cultural innovations that had swept through its swiftly shifting streets. From the recently completed architectural marvel that was the Eiffel Tower, to the awe-inspiring works of a new generation of Impressionist artists, La Belle Époque was truly a time to be alive for many Parisians. But as dreamy as La Belle Époque appeared, its origins were, in reality, far from it.

In 1871, the City of Light was recovering from the disastrous Paris Commune, a short-lived revolutionary government that took power after the Franco-Prussian War. France’s defeat in the war had caused Napoleon III’s Second Empire to collapse, allowing the radicals of the Paris Commune to seize power. Over the next two months, violence and chaos ensued in the French capital as the French Army fought to reclaim the city. As a result, several iconic infrastructures were set on fire and destroyed, including the Tuileries Palace and the Hôtel de Ville, Paris’ iconic city hall. By June 1871, the Paris Commune had fallen, and the new government was looking to restore order and rebuild many buildings in the city.

All Hail the Birth of the Architectural Marvels

Following the relentless building and rebuilding in the city, Paris during La Belle Époque played host to two iconic international expositions, the World’s Fair of 1889 and 1900 respectively. Many of the city’s landmarks were built for these two fairs and have continued to dazzle locals and tourists alike to this day. Examples of such are the Pont Alexandre III, Grand Palais, Petit Palais, and the Gare d’Orsay. But perhaps the most remarkable of all was the Eiffel Tower, the beloved icon of the French capital. Nicknamed the Iron Lady, the Eiffel Tower was the highlight of the 1889 World’s Fair and was the world’s tallest structure at one point. While some intellectuals criticized its lack of aesthetics, the Eiffel Tower eventually became synonymous with Parisian and French pride.

Another key infrastructural breakthrough during La Belle Époque was the Parisian Métro, which is short for Métropolitain. Construction for this rapid transit system began in 1890, with established engineer Jean-Baptiste Berlier helming the overall design and planning. In operation since the turn of the 20th century, the Métro has been known for its unique entrances rich in Art Nouveau influences. Daring and controversial as they were back in the day, these fanciful entrances boasted elaborate features such as decorative cast iron work and hollow cartouches. Designed by famed French architect and designer, Hector Guimard, these breath-taking entrances reflect the aesthetic sensibilities integral to La Belle Époque. About 86 of these masterpieces still exist today as protected historical monuments.

The Innovative Art Movements

In the spirit of innovation and experimentation, La Belle Époque was also a time when art went through a great change. Prior to the 1870s, most artists remained conservative and adhered to the styles favored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. It was known that the organization had preferred works that touched on traditional subject matter such as religious and historical topics. However, a group of artists later banded together to express their disdain toward such rigid interpretations of art. Popularizing non-realistic brushwork and painting everyday scenes, this group came to be known as the Impressionists. It consisted of now-famous artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro. This movement would later influence the artists who spearheaded emerging styles such as Post-Impressionism, as well as Fauvism.

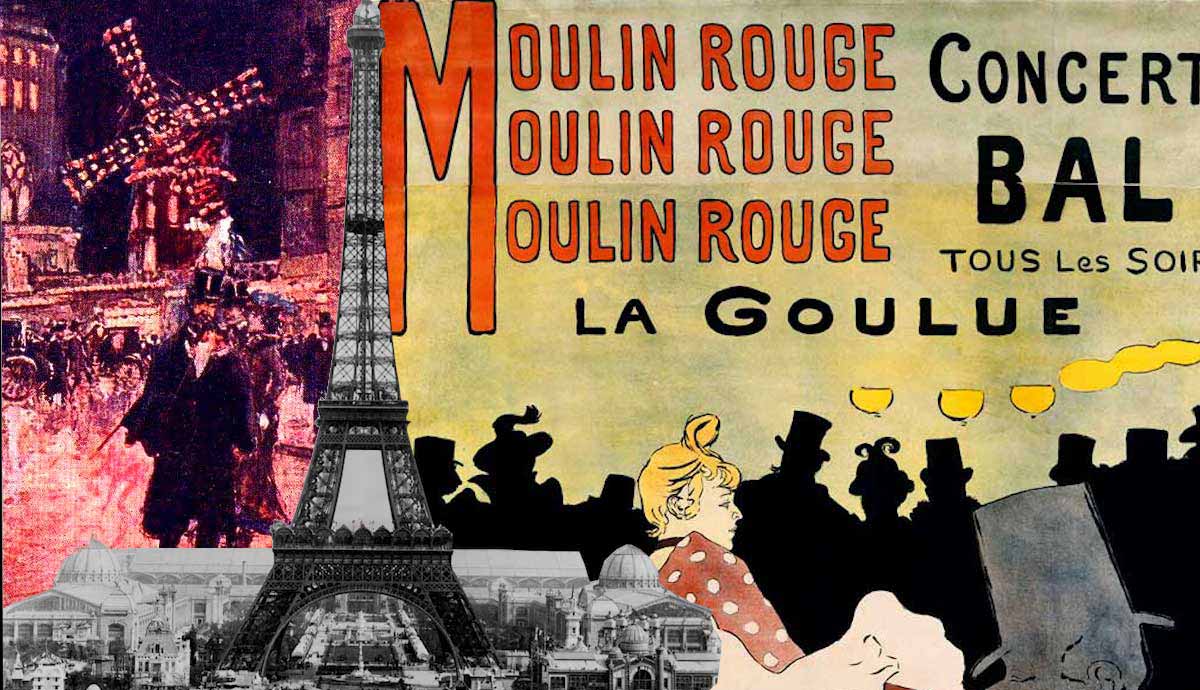

From the mid-1880s onwards, Post-Impressionist artists such as Paul Cézanne and Vincent Van Gogh would continue to push the limitless boundaries of artistic freedom. Characterized by bold brushstrokes, distorted forms, and stylistic abstraction, their works defined the period leading up to the turn of the 20th century. As the 1900s unfolded, it witnessed the birth of newer, more avant-garde art styles such as Modernism, as well as Cubism, which was pioneered by iconic painter Pablo Picasso. This was also concurrent with the popularisation of illustrations and posters, mostly employed to advertise cultural events. Decked out in bright, exuberant colors with Art Nouveau influences, these posters characterized the zeitgeist of La Belle Époque. A household name associated with such illustrative art forms was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, a Post-Impressionist artist whose works were plastered all over cafes, cabarets, and other nightlife spots in fin-de-siecle Paris.

Socio-Cultural Pursuits

With the vibrant artistic community at the forefront of the cultural overhaul, urban leisure and mass entertainment were also slowly gaining momentum. From all corners of society, music halls, cabarets, cafes, and salons were sprouting. One establishment that epitomized this lifestyle was the Moulin Rouge, a popular cabaret in Paris. Founded in 1889 in Montmartre, the Moulin Rouge became one of the world’s most recognizable structures with its iconic red windmill. A hallmark of La Belle Époque, the Moulin Rouge is best remembered as the birthplace of the French Can-can dance, a vigorous dance characterized by high kicks, splits, and cartwheels.

Consumer culture also blossomed. La Belle Époque witnessed the era of department stores, complete with the elements of advertising, marketing, and seasonal sales, all of which we are accustomed to today. Many household names such as Galeries Lafayette and La Samaritaine were established during this period and were credited for expanding the market for luxury goods. At the same time, haute couture (high fashion) was also appealing to the higher echelons of society, with fashion houses making a name in Paris. By 1900, the French capital was home to over twenty high fashion houses headed by famed designers such as Jeanne Paquin and Paul Poiret.

Unrelenting Momentum of New Imperialism

While artistic and cultural liberation revolutionized the pace of life in Paris and the major European cities, the political front too was undergoing massive changes. Unlike the developments on the cultural front, these political changes were less than promising. As the Age of New Imperialism was underway, many of the European powers were establishing vast empires mainly in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. From the start of La Belle Époque to WWI in 1914, African land under European control increased from 10% to a whopping 90%.

Fundamentally, the scramble for colonies was motivated by several factors such as military prowess, national security, and nationalistic sentiments. Great Britain, for example, occupied Egypt in a bid to protect the Suez Canal which determined the maritime superiority of the empire. The British, like all the other European colonial powers, were also eager to expand their empire, having regarded overseas colonies as an important status symbol, and a safe harbor for naval expeditions. The prevailing mentality of a civilizing mission also fuelled the imperialist sentiments as the European powers saw their rule as a means to uplift the colonies politically, economically, spiritually, and socially. Such aggressive expansionism would not only profoundly affect the developments of the colonies, but also trigger the festering tensions between the respective European powers. Along with militarism, and unresolved territorial disputes among other factors, these tensions would eventually culminate in the outbreak of WWI.

With Progress Came New Ideas and Beliefs

Amid unrest and chaos, people were deliberating and experimenting with the notions of anarchism, socialism, Marxism, and fascism, among others. The unorthodox theories of intellectuals like Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Nietzsche were also appealing to more people. Women, too, were fighting for their civil rights in a patriarchal society, fuelling the pace of suffrage movements in Britain, France, and the United States.

Unions too were gaining momentum as workers’ rights became a cause of concern in an increasingly industrialized economy. In a time of vast technological progress, the industrial output of Europe improved by leaps and bounds. For example, France’s industrial output had tripled during this period, registering unprecedented growth figures in the agricultural, communications, transport, and aviation sectors, among others. As such, in this climate, union movements became an important pillar of support for workers seeking fairer remunerations and a better working environment.

The Legacy of La Belle Époque

Undoubtedly an era that witnessed unprecedented changes on artistic, cultural, political, and technological fronts, La Belle Époque ended in 1914 with the outbreak of WWI. The progress and spirit of innovation that had so permeated the society in the span of fifty years culminated in an all-out war in Europe. As the European nations grappled with the power balance within and outside of the continent, simmering tensions erupted from beneath the optimism and exuberance. With technological and cultural advances and increasingly diverse voices competing to be heard, the groundwork for profound changes in many societies was laid. Essentially a period of experimentation and relentless pushing of boundaries, La Belle Époque will be remembered, at its core, as a time of change.