William Hogarth brought to light the hypocritical nature of morals and ethics during the 1700s in England. His distaste towards the French’s propagandist renditions of the lives of the wealthy through Rococo was the inspiration for one of his most popular moral series. With the advent of widespread printing, he was able to spread his views of the actions of the people under a new form of Christianity and a more industrious England, equally snubbing the French and portraying his cynical yet realistic views of the world.

Early Life and Career of William Hogarth

It can be said that there isn’t a lot of information on the life of William Hogarth, however, what is known can give us much insight into how his moral alignments began. To start, he was born to a middle-class family in London. However, the family had fluctuating income due to his father’s bad business deals and debts that he later ended up going to jail for.

Many assume that it was Hogarth’s father who inspired much of the moral direction present in his works, especially due to the fact that it was his father’s debt that prevented Hogarth from going to school which enabled him to apprentice under an engraver in the first place. Furthermore, it can be argued that his paintings, and engravings, give some inclination to his history. In the book, The Works of William Hogarth, it is stated by Sir Robert Walpole, the Earl of Orford, that Hogarth’s works are his history (Clerk 1810), and upon viewing his works one will find that this rings true.

Many of the basic aspects of William Hogarth’s works show interest in those around him. During his time as an engraver’s apprentice and long after, he analyzed the nature of people and their sensibilities in sketches he would make of the faces he saw on the streets of London. It was during the time when he was working and learning to be a proper engraver that another one of his father’s business ventures failed and he ended up in jail, a fact that Hogarth never spoke of.

Hogarth did not finish his apprenticeship as an engraver but left with skills that enabled him to work independently as a copperplate engraver. Eventually, he was able to pay for an education at St Martin’s Lane Academy and learn the foundational and formal skills necessary to work seriously in fine arts. Despite his father’s failings, Hogarth was able to work strictly with intentions to be his father’s successor.

During his career as an English painter, Hogarth made a local name for himself as a portrait painter. For him, that became an unfulfilling endeavor and one that did not pay well. Years after his father’s negligence, it was still evident that the artist was strict with money and wanted to be very money-minded while working freelance. Such matters led him to widen his horizons more, adding social criticisms into his works and conveying a moral message that he valued through his practice.

Where He Focuses His Social Critiques

There are many arguments as to where Hogarth’s moral belief system began. It is possible that his religious beliefs, his relationship with his family, and his experiences with money are what shaped his values and ideals depicted in his work. His fascination with the lives of those around him, as well as his own experiences teetering on a life of scarcity and abundance, set Hogarth up to be able to create works from varying perspectives.

This also made him cynical towards the wasteful and frivolous nature of the upper crust of society. Hogarth was also a known satirist, so during his early career, he already had an eye for social critique. The foundation of satire was always criticism.

As for William Hogarth’s religious pursuits, he was a known Deist: one who believes in a higher power that had created the world and beings that reside within it but takes no action in human lives. Hogarth made works such as Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism and his series Industry and Idleness. His engraving Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism came late into his career, two years before his death. The work was practically considered Hogarth’s magnum opus by Sir Robert Walpole.

This piece is a culmination of people’s willingness to believe nonsense, shown from Hogarth’s perspective. Credulity is the hyperactive willingness to believe that something is real or true regardless of proof. It was something that drove Hogarth mad, be it people’s readiness to believe something based on religion or a rumor. He wanted others to see how ridiculous they had been in their beliefs.

If you look to the right on the engraving there is a thermometer shown. It is measuring the different kinds of the human condition, or what resides within the human heart. From lust to despair and low spirits, much is documented on this thermometer.

The Industry and Idleness series has an engraving called The Industrious ‘Prentice Performing the Duty of a Christian. Here Hogarth lays out the hypocritical nature of Christian duty. The apprentice himself is dutiful, though chooses to be next to the girl he fancies, conveying that his priority is not necessarily the word of god. Secondly, the people in the background are talking amongst themselves. They are not paying attention at all, like the man sleeping behind the young apprentice. Performing is the perfect word to describe this piece as every person present is only there in order to perform their duty. They do not really care about moral teachings.

Hogarth’s distaste of the hypocritical and fanatical nature of Christianity in Europe, exemplified by the French Rococo was the basis of many of his works. This is why there tends to be a focus on the lack of moral behavior of the upper class with his Marriage-à-la-Mode and A Harlot’s Progress.

The Rococo Art Movement and Hogarth’s Distaste

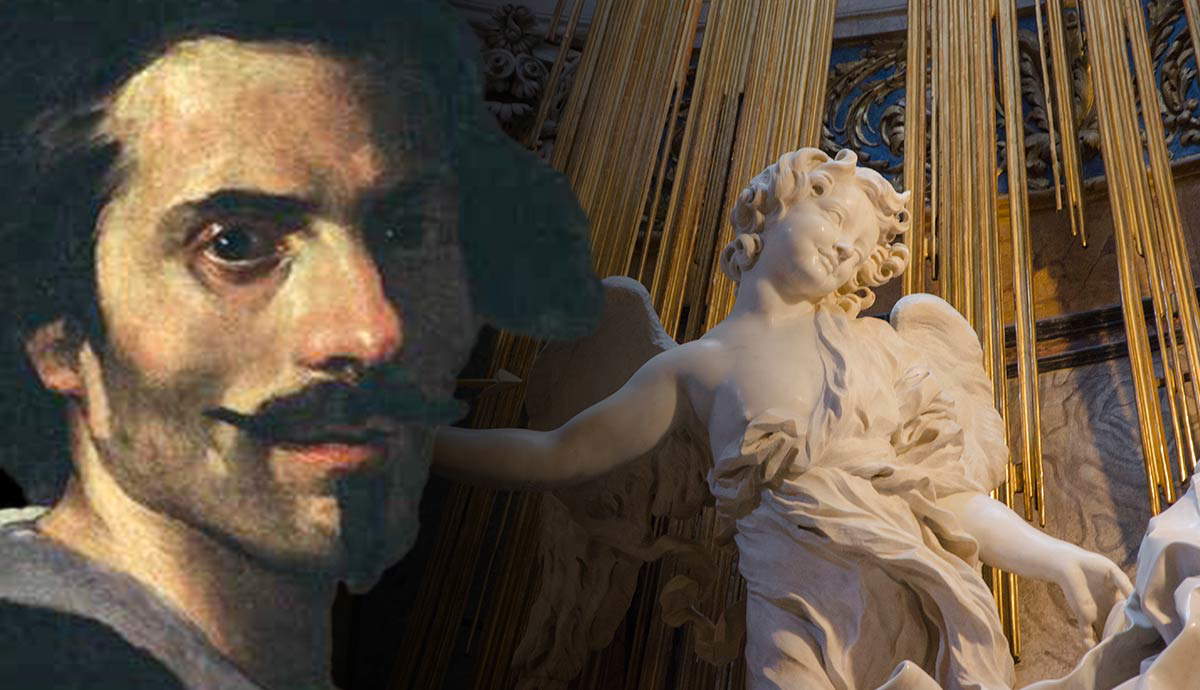

Rococo originated in France during the late seventeen century and persisted well into the eighteen hundreds. It was considered the last leg of the Baroque movement; sometimes it is even considered the Late Baroque. Rococo art took the theatrical and ornate nature from the Baroque and turned it into something flirty and posh. This was unlike works like David by Gian Lorenzo Bernini which were theatrical yet serious in tone and depicted a serious moment within a religious work. The divide between Rococo and Baroque comes down to subject matter, really. When Rococo finally made it to Britain between 1740 and 1750, it was considered a style that was strictly French. But William Hogarth created the aesthetic foundation of British Rococo art.

If we had to compare William Hogarth with any French Rococo artist we could look at Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin as his works focused on the domestic bourgeois without much care for the frivolous things. The main difference would be that Chardin did not choose his subjects in order to shame them but to inform others of the actual daily lives of those around them. This is very reminiscent of the Realism movement and the works of Gustave Courbet and his notable works such as The Stone Breakers.

Hogarth was one of the few English painters that focused on Rococo once it made its appearance in Britain. That being said, he felt that the French views on frivolity, within the upper class especially, were foolish. His response to works like The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard was his series Marriage-à-la-Mode.

Pictorial Sequence and its Importance

During his era of engraving, as well as painting, Hogarth created works that worked in tandem with each other in a sequential manner. He himself in his Autobiographical Notes stated that he found he pioneered the pictorial sequence genre. Some of his first works depicted in pictorial sequence were of a more salacious nature in hopes of acquiring another type of clientele. This work ended up being the foundational work for Hogarth’s first pictorial sequence series, A Harlot’s Progress. He continued working with this subject matter as it was profitable due to reproductive possibilities through engravings. He was also able to take on this task himself. The inspiration behind the title of this series was The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan.

The curator of A Rake’s Progress VI: The Gaming House, at Sir John Soane’s Museum, Joanna Tinworth stated that pictorial sequences “were innovative because the pictorial narratives showed aspects of contemporary eighteenth-century life in series. The locations and characters depicted, often taken from real life, would have been instantly recognizable to Hogarth’s contemporaries” (Tinworth, 2021).

Hogarth used pictorial sequence in his noteworthy series depicting Modern Moral Subjects, such as A Harlot’s Progress, A Rake’s Progress, and Marriage-à-la-Mode. The pictorial sequence was not just innovative but radical in that it forced accountability on the people who were being depicted, creating a space where others have to talk about their own morality and overarching beliefs.

What Put Hogarth on the Map?

A Harlot’s Progress created not only its own genre but consumer base as well. With his subscription-style way of selling and his paintings being his marketing, Hogarth was creating works that people didn’t know they wanted or needed. His pictorial sequence set his works apart as they were meant to hook the viewer and fully engage them with the story within the piece. Creating works that were a bit promiscuous in nature was what the people of the Rococo era needed, and Hogarth fully profited from it, eventually creating A Rake’s Progress.

A Harlot’s Progress: A Critique of the Working Woman

A Harlot’s Progress is a six work series that not only put Hogarth on the map but also forced people to question their own moral and ethical standings regarding the lives of sex workers. William Hogarth referenced many real-life people that patrons would recognize and fully immerse themselves in their work. For example, the main character in the series is Moll Hackabout who is suspected to be a combination of two women, Moll Flanders and Kate Hackabout. Moll Flanders was the name of a novel by Daniel Defoe that depicted the adventures of Moll Flanders. Kate Hackabout was a renowned sex worker in England. The name was made to be ironic and have an underlying dark tone.

The first plate of the series was an image of our main fictional character arriving in London and seeking a job as a seamstress. She is instead tricked, as per the goose in one of her bags, into believing that she is given an opportunity to do reputable work for Elizabeth Needham, a known madame in 1700s England. Moll is a naive character that was easy to manipulate, which is what William Hogarth wished to portray here, showing the lack of full consent on Moll’s part.

The foreshadowing of her inevitable downfall is shown with the pans to the left just before their fall. In plate two we see that she has now become the mistress to a wealthy merchant, having lost her innocence to man and a world of luxury that we see laid out messily before her. The paintings hanging around her apartment further exemplify her promiscuity and morally corrupt state.

In plate three we see her fall, as she is now riddled with syphilis. Her maid is older, unlike her maid from plate two, giving the viewer the idea that her run as a working woman is coming to an end and that her youth is fleeting. Furthermore, in plate four, William Hogarth brings awareness to the plague of the fast and easy money of the time. The image shows Moll entering prison with others, her wares no longer her own. She stands beneath a sign that says “Better to work than stand thus,” giving us further insight into Hogarth’s overarching belief for those who do not take the moral money-making path. Moll is shown as having no allies with her maid stealing shoes from her on the bottom right.

In the finale of this series, Moll becomes ill and then dies due to venereal disease. She also has a son who will bear the same fate as her. He sits beneath her coffin in plate six, while people who were said to have known and cared about Moll use her coffin for hors d’oeuvres and drinks, disrespecting her even after her death. Moll’s story is supposed to be the ultimate cautionary tale and ethical anecdote. The series is satirical but its dark tones were not missed by those who patronized this series.

Marriage-à-la-Mode by William Hogarth

William Hogarth’s Marriage-à-la-Mode is a series of six paintings that was the finale to his pictorial sequence series, with a satirical focus on the married life of the so-called illustrious and sought-after people of the upper class. Hogarth wanted people to question the works of the French Rococo, and realize how propagandist it really was. He wanted to show that many of these marriages of the upper class were not based on love and that the intriguing, frivolous nature shown in the works of Rococo was far from the truth.

Two pieces that exemplify Hogarth’s resentment of Rococo are paintings number two and six from the series. One is shown from the perspective of a man and the other is made from the perspective of a woman. This gives us a well-rounded view of Hogarth’s insight.

The Suicide of the Countess, the sixth and final painting of the series, should be analyzed here first, as it ties in well to Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress. This piece takes place in the home of a bourgeois English family home. The family is not of the highest class seeing as their home looks more dreary. This is shown through their starved dog, the weathered walls, and the lack of noticeable works of art. To the left, we see a dying countess and her husband removing her wedding ring after finding out that she had an affair with a man who was just pronounced dead. The man who stands to the far right in tan clothing is the messenger. We know this from his posture. The maid holds the countess’ daughter up to her in order to say goodbye as she dies from suicide, her lover’s death weighing on her.

It is a known medical fact that syphilis can be transferred to the fetus through the placenta during pregnancy. One of the trademark symptoms of syphilis was wart-like patches on the skin. There is a spot on the little girl’s left cheek that could be a tell-tale sign of syphilis. If this is the case wouldn’t the count have known about the affair? If so, that shows the immoral nature of their marriage and the lack of loyalty to one another.

Dogs tend to symbolize many ideas in art, such as fidelity, wealth, or love. We see this in works like Venus of Urbino by Titian and Anne Louis Girodet Roucy-Trisson’s The Sleep of Endymion. Dogs are a motif that can be seen in many of this series’ pieces. In The Suicide of the Countess, the lack of fidelity in the relationship is what can be taken into account. The dog shown as starving is representing the lack of love in this marriage as well as the countess’ lack of fidelity. The dog sneaking to snatch the food from the table parallels the countess’ affair in an attempt to fulfill her need for true love, behind her husband’s back. William Hogarth perfectly displays the lack of romance and the dull nature of an affair that the French Rococo artists displayed in a playful and positive light.

The second piece from the series TheTête à Tête has more of a comedic nature to it than the previous, tragic work. This painting displays the misery that the husband endures this time. Just like the previous painting, there is a mutual lack of interest in the marriage. The dog to the bottom right looks away from the couple, representing the idea that both of them are looking for entertainment elsewhere. The husband sits exhausted in his chair looking off into space disinterested. We know that he is coming home from a brothel due to a lady’s cap in his pocket. The wife is physically separated from her husband, stretching in exhaustion from the party that happened the previous night. However, she has a happier look on her face than him. The room is shown as messy and neither of them seem to care.

Behind them, above the mantle, a painting of Cupid is shown. It is however partially covered by a bust. The bust’s nose is broken which is a symbol of impotence that conveys the sexual strain in their marriage. It is important to know that the people were William Hogarth’s prime inspiration as there was a surplus of immorality and hypocrisy during the advent of Methodist ideology and an economic peak. This happened due to England moving into the industrial age and trading more. His pictorial sequences and moral tales are a culmination of the loss of fear of the consequences of one’s actions.