It was a grand affair, one that resembled the wedding of Anna Ioannovana and Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Kurland just two weeks earlier. This is the wedding of Iakim Volkov, Tsar Peter the Great’s royal dwarf.

Iakim Volkov’s wedding, held on November 14, 1710, was more than just a wedding. It was entertainment. It was a parody. And, perhaps most importantly, it was an expression of power.

*Editor’s Note: Today, terms such as “little person,” “LP,” “dwarf,” and “person of short stature” are all generally accepted when referring to people with dwarfism. However, when referencing historical records, TheCollector refers to people by their name rather than a label unless it is relevant, as is the case for this article. For more information, please consult the Little People of America website.

Iakim Volkov’s Wedding

Peter the Great of Russia had an affinity for dwarfs or, at the very least, was fascinated by them. Like many of his contemporaries (and predecessors), Peter kept dwarfs close for companionship and amusement alike.

Iakim Volkov, Peter’s royal dwarf, was as much a drinking buddy as he was a servant to the tsar. It’s unclear when Volkov arrived at Peter’s court, but he was one of dozens kept by the tsar. It was common practice for a dwarf to be placed in a pie at celebrations, only to burst out when Peter cut into the pastry. Peter also held mock ceremonies featuring dwarfs, namely funerals and weddings.

It’s a wedding with which Volkov is most associated. On the heels of the marriage of Peter’s niece, Anna Ioannovana, and the Duke of Kurtland Fredrich William, Peter held a wedding for Volkov.

Anna was one of the three daughters of Tsar Ivan V, Peter’s half-brother and former co-ruler. Anna’s marriage to the Duke was arranged by Peter and took place in his new capital St. Petersburg. Much of the city was under construction as Peter sought to modernize Russia.

Anna did not willingly enter into the marriage, but the wedding took place on October 31, 1710 nonetheless. Peter oversaw the wedding, although a dwarf served as the master of ceremonies. Dwarfs were in abundance at the ceremony, with at least two jumping out of pies as part of the festivities that followed during the two days after the event.

Two weeks after Anna’s wedding, a comparable wedding in the same location and a similar spirit took place. Again arranged by Peter, Volkov was set to marry an unnamed woman with dwarfism. Leading up to the event, all of the dwarfs in the vicinity of St. Petersburg and Moscow were called to the city to attend.

Matrimonial Mockery

According to Danish diplomat Just Juel, it was two dwarfs who delivered the invitation to his residence and, on the day of the event:

“The Tsar himself seated the dwarfs in boats. The groom [Iakim Volkov] crossed first with the Tsar. Behind them went one of the most handsome dwarfs, with a small marshal’s mace in his hand. Then there followed in pairs eight groomsmen dwarfs; then the bride accompanied by two escorts… Behind the bride walked 14 dwarfs in pairs and at the end 35 more dwarfs. The oldest, ugliest and biggest brought up the rear. I counted 62 dwarfs altogether, although it is said that there were more.”

Dwarfs were dressed in Western-style clothing, and once they were inside the cathedral, the wedding was carried out hurriedly at the urging of the Tsar. This had also been the case with Anna, although during the dwarf wedding, “the priest himself was so overcome by laughter that he could barely read out the prayers.” Once the ceremony was over, the dwarfs returned to their boats and went to the wedding feast with the other guests.

The hurried nature of both Anna’s and Volkov’s weddings demonstrates the Tsar’s lack of patience for traditional ways. Both shortened ceremonies also represented the authority of the Tsar to dictate how religious rituals were carried out.

The Royal Dwarf’s Reception

The wedding feast for Volkov and his bride was a spectacle of sorts. Dwarfs were seated at small tables in small chairs while nobles sat at large tables around the room facing in to watch. Dancing featured drunk dwarfs who “could fall over… [and] could not get up again” until another dwarf came to their aid. Drunken brawls broke out as “laughter and noise” ensued. Juel offered some details:

“While they danced they quarrelled and bickered like nothing on earth, slapped the female dwarfs on the face if they didn’t like the way they danced and so on.”

Volkov also had a role in preparations for the post-wedding celebration, according to Juel:

“As the Tsar’s personal dwarf, the newly-wedded groom had been trained in various skills and he himself had prepared a small firework display… [although] the celebrations ended early and the fireworks were not set off.”

In many ways, Iakim Volkov and his bride were pawns in Peter the Great’s efforts to mock traditional practices and perhaps turn a mirror on nobles who behaved similarly at comparable events. Peter the Great was determined to modernize Russia, and, in his view, this meant establishing the foundation of a secular culture. Russian traditionalists were inclined to put religious tenets above all else, including mandates from the tsar.

Peter involved himself in ecclesiastical matters and even presided over synods of the Russian Orthodox Church in his efforts to wield power.

Dwarfs and Court Culture

In many ways, the presence of dwarfs in Peter’s court was indicative of a larger court culture throughout Europe. The practice extended back into antiquity. Author John Woolf, in his book The Wonders, summarized the phenomenon:

“Dwarfs were around in the courts of Ancient Egypt, China and West Africa. Alexander the Great (356BC-323BC) gathered a whole retinue of dwarfs. The Romans collected dwarfs as pets, placing some in gladiatorial rings to fight with Amazons, and tossing others across the amphitheatre for entertainment… By the Middle Ages, dwarfs were kept side-by-side with monkeys, sometimes travelling between royal households in birdcages.”

Coveted and exploited, dwarfs were both a symbol of status and a source of entertainment. As a result, dwarfs were treated differently depending on location, their abilities and skills, and the overall esteem with which they were held.

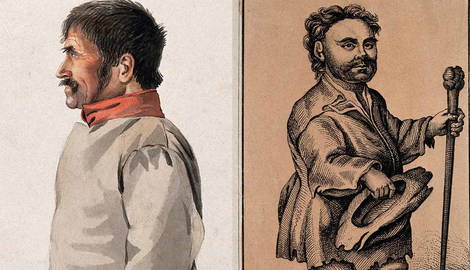

Jeffrey Hudson (1619-1683), for example, was one of Queen Henrietta Maria’s dwarfs. The British-born dwarf was presented to King Charles I’s wife in 1626 after he charmed the Queen by bursting out of a pie. Formerly in the care of the Duke and Duchess of Buckingham, Hudson later accompanied the Queen when she fled England for France during the English Civil War. While in France, Hudson killed a man during a duel and was subsequently expelled from the Queen’s court.

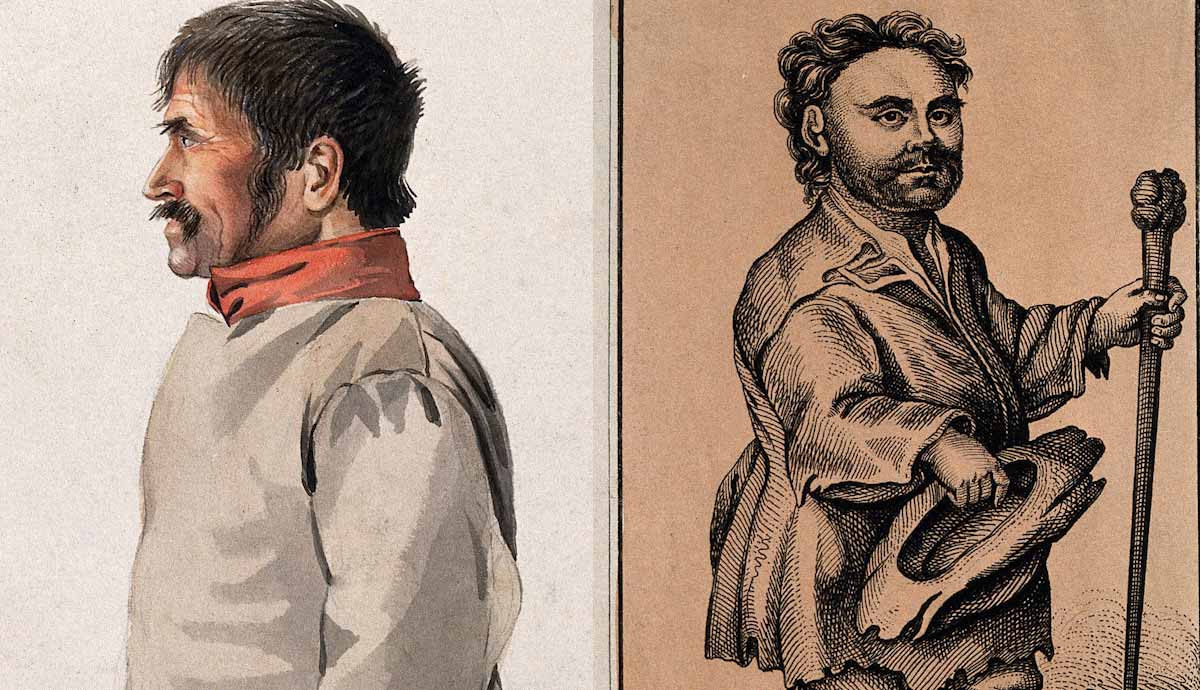

Joseph Boruwlaski (1739-1837), a near contemporary of Volkov, was a Polish-born dwarf who spent his life touring European courts as a musician. He spoke numerous languages, enchanted women with his charm, and married a Frenchwoman named Izalina Bourboutan in 1779 or 1780. Later, Burowlaski went to England, where his marriage crumbled. He befriended nobles and royals, ultimately making money by publishing his memoirs.

Boruwlaski, never an official court dwarf himself, crossed paths with Nicholas Ferry, the court dwarf of King Stanisław Leszczynski of Poland, around the year 1760. Called Bebe, Ferry purportedly had a bile temperament and was so jealous of Boruwlaski that he attacked him. King Stanisław reportedly tried to educate Ferry but, as one observer noted,

“Bebe can really be brought forward as a better proof for the theories of Descartes about the souls of animals, than a monkey or a poodle… I must confess that I have never cast an eye on Bebe without feeling repugnance and secret horror, inspired by this vile caricature of human nature.”

Ferry’s health failed while he was in his teens. By the time he died in 1764, he’d become an invalid.

Another dwarf of note was Richebourg (1768-1834). He was in the service of Louis Philippe I’s mother, Louise Marie Adelaide de Bourbon. During the French Revolution of 1848, he was reportedly disguised as a baby and given military information to smuggle to Royalist supporters.

A Royal Dwarf in the Russian Court

The power Peter the Great demonstrated by putting Volkov on display was characteristic of royals throughout history. Peter was no doubt entertained by his court dwarf, but he also trusted him to some extent. That said, he was not above exploiting Volkov for his own purposes.

Volkov’s wedding simultaneously demonstrated Peter the Great’s authority in Russia and the extent to which Russia needed to change. Peter had the ability to manipulate the events that so clearly exemplified what he identified as antiquated.

Peter the Great died in 1725, and shortly afterward, Volkov was “to be beaten brutally with a birch rod and to be banished… [to a] monastery to the end of his life.” Volkov had allegedly spoken against Peter the Great, but he never actually served out his sentence. The monastery he was supposed to go to would not pay for his transportation to their grounds.

From a wedding fit for a dwarf to life as an unwanted outcast, Volkov’s plight represents his dependency on Peter the Great. It was also an example of just how quickly circumstances could change for a dwarf at court.