Ilya Repin was born in the Russian Empire on the territory of present-day Ukraine. He was one of the most interesting realist painters in Europe of his era. Over the long years of his career, he created hundreds of portraits and history paintings that illustrated the remarkable yet often mythologized moments in his land’s history. For his contemporaries, he was a talented eccentric and a truly marvelous and outstanding figure. Read on to learn more about the master of Russian Realism, Ilya Repin.

1. Ilya Repin Had Ukrainian Heritage

Although usually labeled as a Russian painter, Ilya Repin was born near Kharkiv, in the present-day territory of Ukraine. His father was a former soldier who turned into a horse merchant, while his mother, a literate and well-read woman from a military-related family, ran a small school where she taught local children and adults to read, write, and count. Ilya’s obsession with art started with a small gift from his cousin – a pack of watercolor paints. As the artist remembered, his mother had to physically move him to the dining room to force him to eat away from his new hobby. Soon, he became sick and almost died. In agony, the boy asked only one question: if God would allow him to paint in heaven?

He soon recovered, and at the age of just 11, he began studying topography and icon painting. His talent soon received recognition, and by the end of his studies, a sixteen-year-old Repin received a job in a traveling group of icon painters. Soon, he moved to Saint Petersburg to study art professionally and started to gain prominence in the circles of art lovers and collectors.

During the following years, he would travel extensively, spending three years in Paris, admiring the work of the French Impressionists. After several decades spent in Moscow and Saint-Petersburg, he settled in Finland, where he spent the rest of his life. Still, despite all his travels and temporary homes, he remained connected to the culture of his native Ukrainian region. He taught his children Ukrainian folk songs and tales.

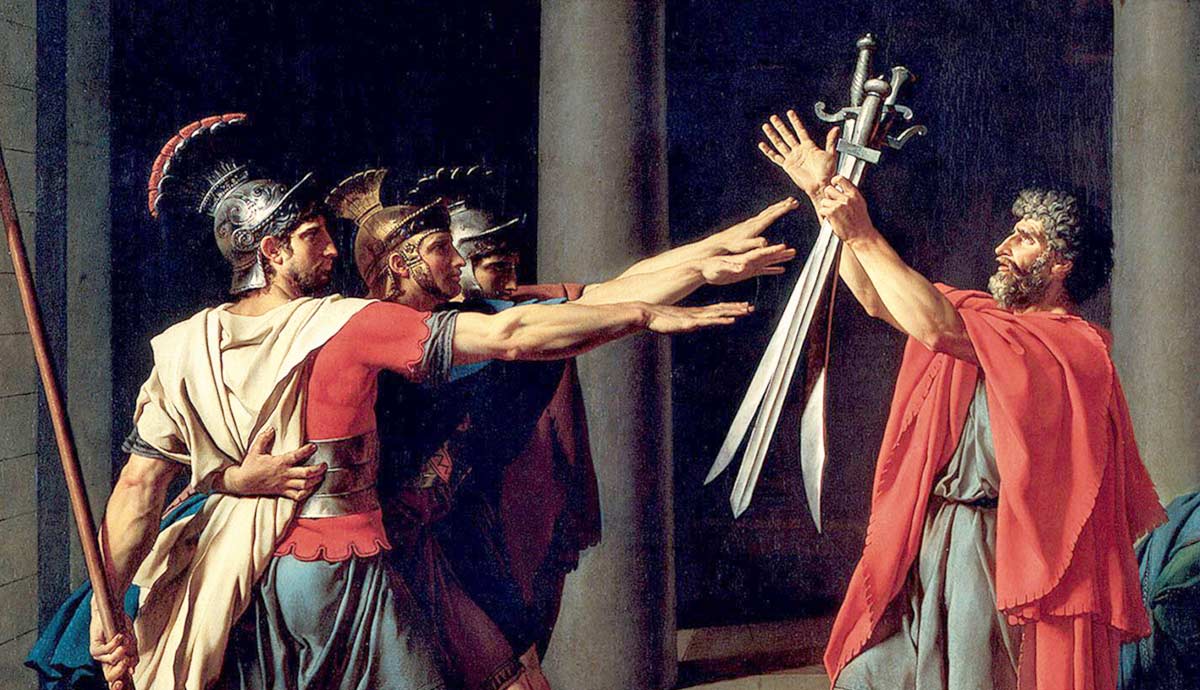

During his long career, Repin repeatedly returned to the scenes of Ukrainian Cossacks, their spirit, culture, and semi-mythological scenes from their history. These scenes showed a remarkable intensity of color and swift dynamism. Repin was a well-known master of complex, multi-figure composition, yet his Cossack works demonstrated it to the fullest extent.

2. Repin Was a Beloved Art Teacher

Rather quickly, Repin became famous as a prolific painter of history scenes and portraits. He worked tirelessly and carefully, often arranging dozens of figures in his compositions. The component of national culture was crucial for his work. He painted characters of different classes and ranks, showing the diversity and inequality of the time he witnessed.

In the mid-1890s, Repin started teaching at his alma mater, the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. Dozens of artists went through his workshop, with many soon becoming equally famous as their teacher. Painters like Valentin Serov, Boris Kustodiev, and Zinaida Serebriakova were guided and trained by Repin. Unlike many other art teachers, he encouraged women artists to paint more and not give up art after getting married. Repin’s workshop had an unusually high number of women constantly present, sketching still-lifes and nude models. He was also fiercely protective of artistic innovation, supporting his avant-garde-leaning students from the wrath of the conservative Academy administration.

3. The Repins Were Unusually Progressive For Their Time

During his lifetime, Ilya Repin had a reputation of an eccentric and he was often quietly laughed at by his friends and acquaintances. Inspired by the example of his second wife, a suffragette and vegan activist Natalia Nordman, Repin adopted a plant-based diet. Nordman published an entire book of vegan recipes, including a rabbit stew made from carrots, cranberry steaks, and beetroot coffee. She believed a vegan diet was beneficial not only for one’s health and morals but for global welfare, potentially solving the world hunger problem. She refused to wear fur, stuffing her winter coats with pine needles. Ilya eagerly supported her beliefs, trying to promote them against his confused friends.

Repin’s visitors frequently complained about the family’s habits. Some of them snuck meat products to eat them behind closed doors. Another issue for unprepared guests was the absence of servants in the household. Instead, walls were covered with signs handwritten by Natalia reading Do It Yourself and Servitude is Shameful. According to contemporaries, Repin was completely mesmerized by his wife, although many saw her as too weird.

4. He Was an Incurable Perfectionist

Ilya Repin had a rather annoying habit of endlessly retouching his works, even after they were sold. He was never content with the result, always suggesting a new color scheme, a new gesture, a new facial expression. Analysis of present-day paintings has revealed that many of his works exhibit traces of later modifications, occasionally undergoing radical transformations such as shifting the background tone from reddish ochre to blue. Not every correction was a successful one. Repin’s contemporaries sometimes complained that the artist had ruined some of his paintings with his excessive perfectionism.

The person who suffered the most from Repin’s aspirations was Pavel Tretyakov, the famous art collector and the founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Apart from a professional relationship (Tretyakov bought several dozens of paintings from Repin) the artist and the collector shared a long friendship. During his visits to the gallery, Repin always tried to repaint one detail or another and he was usually abruptly stopped by Tretyakov. Once, the painter snuck into the museum while Tretyakov was away and repainted several of his most famous works, including They Did Not Expect Him and Ivan The Terrible and His Son. Outraged, Tretyakov officially banned Repin from entering the gallery and even had to personally retouch some of his work.

5. Repin Was Sympathetic to the Revolutionary Cause at First

Despite his status as a popular painter loved by the authorities, Repin was critical of the violence and oppression exerted by the Tsarist regime. In the late 1870s, he started his so-called Revolutionary series that focused on the fates of Russian revolutionaries, mostly belonging to the Socialist group Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will). The NV members planned to overthrow the regime by arranging assassinations of important government officials, including Tsar Alexander II who was murdered in 1881. Repin’s paintings showed the revolutionaries as people of immense willpower and intellect, ready to withstand torture and sacrifice their lives for a better future.

Yet, after the 1917 Revolution, Repin was utterly disappointed and disgusted. He remained in the newly independent Finland and refused to return to Saint-Petersburg. In his letter to a friend, he expressed his fear that the new Soviet state had no room for art museums anymore, but only for “museums of Revolution that were full of its heroes’ bones, their mutilated body parts, and the bloodied rags they wore.” His post-revolution paintings were equally pessimistic. One work depicts a Red Army soldier taking away a piece of bread from a whaling child.

6. Ilya Repin’s Paintings Keep an Unsettling Mystical Fleur

Repin’s works are infamous among art historians for the unnerving amount of tragedies and incidents associated with them, especially when it comes to the famous painting Ivan The Terrible and His Son. Soon after the artist completed the painting, his right arm became paralyzed, leaving him unable to paint. Repin then learned to paint with his left hand, fixing the palette with his neck. Over the following years, numerous reports stated the distressing effect of the painting on mentally unstable visitors.

In 1913, a young icon painter slashed the work with a knife, completely destroying the figures’ faces. The curator responsible for the painting’s safety soon committed suicide, and Repin had to paint the damaged segment anew. A century later, the work was attacked again, this time with a metal pole that broke the protective glass.

A string of mysterious deaths followed Repin’s creative pursuits. Many of his models, even young and seemingly healthy, died within weeks after working with him. Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, the architect of the unprecedented economic and social growth of the Russian Empire, was murdered in Kyiv soon after Repin finished his portrait. Composer Modest Mussorgsky died a few days after his painting was completed. However, Mussorgsky’s death was certainly not accidental since Repin visited him in a hospital recovering from an acute episode of alcohol delirium.