From the 8th century CE to the turn of the 16th century, a swath of the Iberian Peninsula was under Islamic control. The legacy of Moorish Spain can be felt in everything from science to agriculture, language, art and architecture. Preserved in Andalusia today, are many elaborate palaces, bold fortresses, and former mosques with minarets that are now bell towers. Communicating a greater truth through intricate geometry, these monuments are rich with tessellated tile patterns, woodcarving, calligraphy, and elaborate plasterwork.

1. Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

Upstream from Seville on the Guadalquivir River, Córdoba became a provincial capital in the early 8th century. By the 10th century, Córdoba was a cultural and economic beacon, rivaling Constantinople or Damascus. At that time the city teemed with scholars and polymaths and had as many as 300 mosques and 100,000 shops and residences.

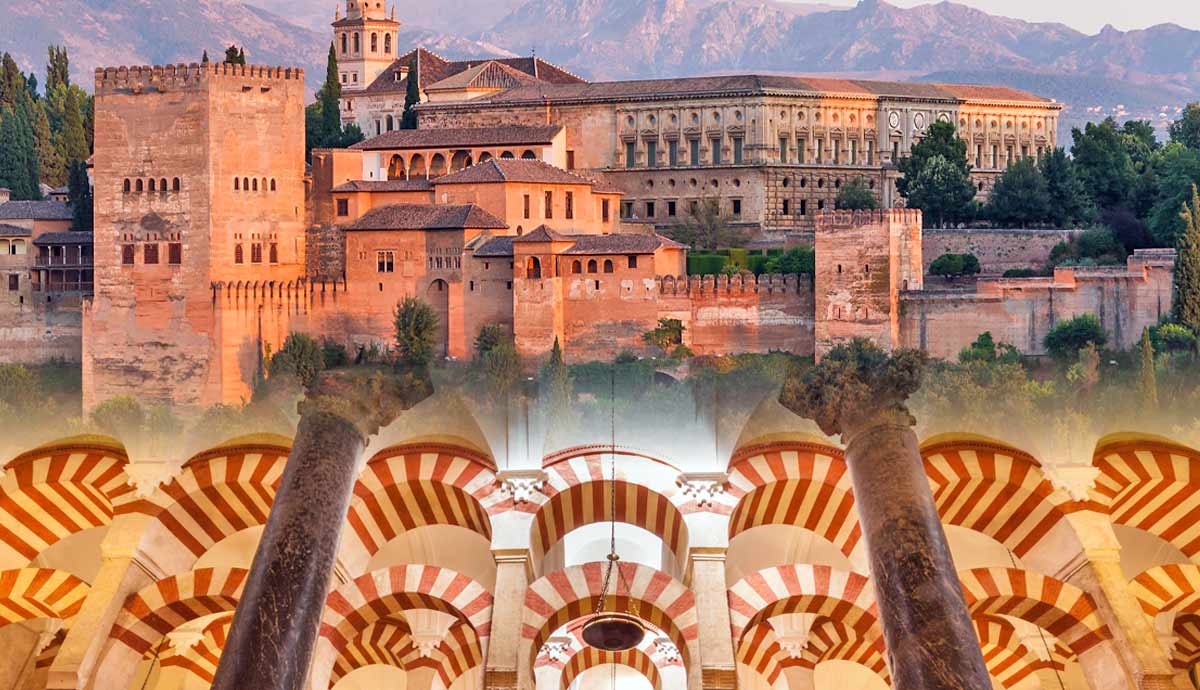

Testifying to that status is a mosque-turned-cathedral, begun in the 780s. Held as the single greatest piece of Islamic heritage in Spain, this extraordinary monument was enlarged in five clear phases before it was Christianized during the Reconquista in the 12th century.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba was once second only in size to the Holy Mosque in Mecca, and from its beginning, it informed Western Islamic architecture. For instance, this building has the first recorded use of double arches, as well as a novel combination of brick and stone, both of which stand out in the magnificent 10th-century prayer hall.

The double arches in the prayer hall are an example of ingenuity, in response to the height of the columns. As was common in Moorish architecture, the columns are reused Roman elements removed from sites in the area. There are more than 1,200 in the building, carved from a variety of materials including marble, onyx and jasper.

Very little changed in the centuries after the mosque became a cathedral, and it wasn’t until the 1500s that the Renaissance nave and transept were added. Before that came the stunning Royal Chapel, designed in the Mudéjar style — Islamic-inspired art produced for Christian patrons.

What is now the bell tower is a former minaret. In this instance the 10th-century Islamic origins of this structure are hidden beneath Renaissance reconstruction work following earthquake damage in the 16th century.

2. Madinat al-Zahra

In 929 CE, after consolidating regional power, the Emir of Córdoba, Abd al-Rahman III (890-961) declared himself Caliph of Córdoba. This made him the leader of all muslims in al-Andalus, and protector of Jews and Christians. The title asserted a continuity between himself and his ancestors, the Umayyad Caliphs. Originating in Arabia, the Umayyad Caliphate drove the early spread of Islam including the conquest of much of Iberia.

Abd al-Rahman III is remembered as a champion of the arts, who oversaw Córdoba’s apogee as a European center for thought and culture. All he needed was a palace suitable for his new elevated title, which he duly built on the course of a Roman aqueduct, three miles out of Córdoba.

Madinat al-Zahra, meaning the “Radiant City,” had a short lifespan. It was sacked and abandoned in 1010, just seventy years after construction began. First excavated in the early 20th century, the site survives as an unadulterated document for the artistry and splendor of al-Andalus in the Early Medieval Period.

The complex, only a small fraction of which has been uncovered, is made up of grand reception halls, offices, baths, workshops, a mint, a great mosque, barracks, and aristocratic residences.

A centerpiece is the reception hall, the Salón Rico, which has survived almost intact. Supported by reused ancient columns are arches with alternating bands of color, while the walls have highly detailed vegetal arabesques. These are carved on limestone panels and have a repeating Tree of Life motif. On the back wall, a blind arch marks the site where the Caliph would have sat.

3. The Giralda

Under the Almohads in the 12th century, the capital of Al-Andalus switched from Córdoba to Seville. During this period a new Great Mosque was built in the city, on a similar scale to Córdoba. It was accompanied by a towering minaret completed in 1198 using a lot of spolia, including material salvaged from previous Umayyad architecture.

The completed structure stood more than 300 feet tall, with ramps winding to the top, instead of steps. These were wide and had enough vertical space to accommodate beasts of burden.

The facade on the middle section of the tower retains its 12th-century Islamic decoration. This includes the sebka, comprising a dense matrix of interlacing blind arches surrounding the windows, which have multilobed and horseshoe arches.

The Reconquest of Spain reached Seville in the mid-13th century and the city experienced an enormous influx of wealth. This continued through the Age of Exploration—Christopher Colombus is interred in the cathedral—and into the Early Modern Period when Seville was designated the sole Iberian trading port with Latin America.

The Christianized former mosque, poorly maintained and damaged by earthquakes, was replaced in the 15th century by a late Gothic cathedral on a vast scale. With five naves, Seville Cathedral is the largest Gothic church in the world.

After its conversion from minaret to belfry the Giralda was capped with a mid-16th century Renaissance extension to house the bells. Crowning the building at more than 340 feet is the theatrical Giraldillo weather vane, weighing more than 3,300 lbs. The tower soars above the Patio de los Naranjos, a sahn (courtyard) surviving from the Islamic period.

4. Alhambra

Even more significant than the Giralda, this monumental palace and garden complex has been continuously occupied since it was developed in the 13th century. The consequence is an astonishing state of preservation at what is considered the high point of Western Islamic architecture.

The Alhambra was initially built in the mid-13th century on high ground above the rest of Granada for the first Nasrid emir, Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar (1195-1273). Following the Reconquista, the complex immediately became the court of the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella. In fact it was at the Alhambra that Christopher Columbus received permission for his first voyage in 1492.

For Moorish finery, the priorities are the Nasrid-era Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions, built at the start and end of the 14th century respectively. At every turn, visitors are confronted with exceptional artistry, including the kind of hypnotic zellij tilework that captivated M.C. Escher, and the muqarnas, intricate stucco dome decorations comprising hundreds of little cells.

Touring the Comares Palace, highlights include the Court of the Myrtles with its daintily carved porticoes or the famed Hall of the Ambassadors. These seven chambers abound with painstakingly realized mosaic tiles, stucco, and Quranic inscriptions, beneath a domed wooden ceiling comprising highly detailed latticework. The level of skill and imagination rises at the Palace of the Lions, renowned for its absurdly detailed muqarnas vaults in the Sala de los Abencerrajes and the Sala de los Reyes.

There is an intoxicating sense of cultural cross-pollination in the ceiling paintings depicting Nasrid rulers and court scenes. Given how rare pictorial painting is in Islamic art, these were likely painted by Christian artists.

Elsewhere, on the Alhmabra’s northern wall, the Torre de la Cautiva (Tower of the Captive Woman) is a small palatial residence. Inside, the lower walls are adorned with mesmeric zellij tiles, with highly sophisticated geometric patterns, beneath a strip with Arabic inscriptions from the Quran.

5. Alcazaba of Málaga

Pitching steeply into Málaga’s natural harbor, Gibralfaro is a hill that has been fortified since the Phoenicians founded a colony here more than 2,700 years ago. The city’s importance grew as the Umayyad Caliphate collapsed, ushering in the Taifas, a patchwork of independent kingdoms and principalities. In the 11th century Málaga became the seat of the short-lived Hammudid Dynasty.

Later, in the 13th century, the city became an essential port for the Nasrid Emirate of Granada, and was visited by the famed traveler and chronicler Ibn Battuta in the 13th century. He described Málaga as one of “the largest and most beautiful towns of Andalusia.”

Surveying the city from its perch was the Alcazaba of Málaga, an immense fortified palace complex protected by two layers of walls. Indeed, the scale was extraordinary, at more than 320,000 square feet, although the present Alcazaba is around half of that.

As with other landmarks in this article, the structure was seminal, informing military architecture for the Taifa Period. Much of the Alcazaba dates to this time, with formidable crenelated walls safeguarding an inner enclosure of gardens and pavilions on the summit. The beefed-up defenses illustrate the instability of the era and culminate with the Torre del Homenaje (Tower of Tribute) on the east side.

There are two distinct palaces within the walls. The southernmost, with its arcaded pavilions, is from the Taifa Period in the 11th century, and takes inspiration from Madinat al-Zahra. Particularly celebrated are the vegetal carvings on the horseshoe arches giving way to the main hall.

Adjoining the Taifa palace is the later Nasrid palace from the 13th century. The priority here is the pair of courtyards, with basins framed by lozenge tilework that is all original.

6. Alcazaba of Almería

In the 10th century, Abd al-Rahman III, a familiar name at this point, ordered the construction of this citadel posted on the ridge high above the water in Almería.

Artistry takes a back seat at Alcazaba of Almería, which impresses for its commanding location and magnitude. Over several phases, it became the second-largest fortified complex from Spain’s Islamic period. Almería flourished as a port city under the Nasrid dynasty, and by the 16th century, the Alcazaba comprised three enclosures connected to the city walls.

Looking over the city at the south end is the Torre de los Espejos (Tower of Mirrors), the modern entrance to the Alcazaba, thought to have been used for communication in Medieval times. From here there’s an all-encompassing view of the city, sea, and mountains.

Behind is the first enclosure, which once consisted of a military camp, cemetery, and place of refuge for the populace during sieges. This enclosure was largely destroyed in an earthquake in the 16th century, one of many to hit the site. Today the space has been landscaped with Moorish-style gardens.

The archeological interest lies in the second-enclosure to the northwest. This served as the residence for rulers, accompanied by mosques, shops, baths and humbler homes. One element that has survived the earthquakes is the set of cisterns, replenished by wells descending deep into the ridge. Close by are baths in the Roman style, a reconstructed home, and a former mosque which was turned into a chapel under Ferdinand and Isabella in the late-15th century.