Most of us are unfamiliar with the early years of Jesus of Nazareth. The canonical gospel offers scant details about this period, prompting questions about why such narratives were omitted. Could there be deliberate concealment? The Infancy Gospel of Thomas presents stories about Jesus’s youth, dating back to the mid-to-late 2nd century. Its classification as a Gnostic text stems from references to it in the writings of Hippolytus of Rome and Origen of Alexandria. Yet, uncertainty persists regarding whether these references allude to The Infancy Gospel or the Gospel of Thomas, discovered in Nag Hammadi in 1945. Early Christian authorities dismissed The Infancy Gospel of Thomas as heretical, considering it fictitious and blasphemous.

Parallels to Genesis

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas begins with Jesus of Nazareth at the age of five. The significance of his age isn’t explicitly explained, though it may simply serve to emphasize his early childhood. Right from the beginning of the discussion about Jesus, the writer subtly alludes to language found in the Book of Genesis, “he gathered together the waters that flowed there into pools, and made them straightway clean, and commanded them by his word alone” (M.R. James translation).

One can hear an echo of Genesis 1 1-3 when God says, “Let the waters under the sky be gathered together into one place and let the dry land appear.” This allusion serves to strengthen the portrayal of Jesus’s divinity and liken him to the God depicted in Genesis, who also commands and orders the elements. Whether it is the separation of clean and dirty water as a child or the creation of the heavens and the earth, the emphasis lies in the power of his spoken words.

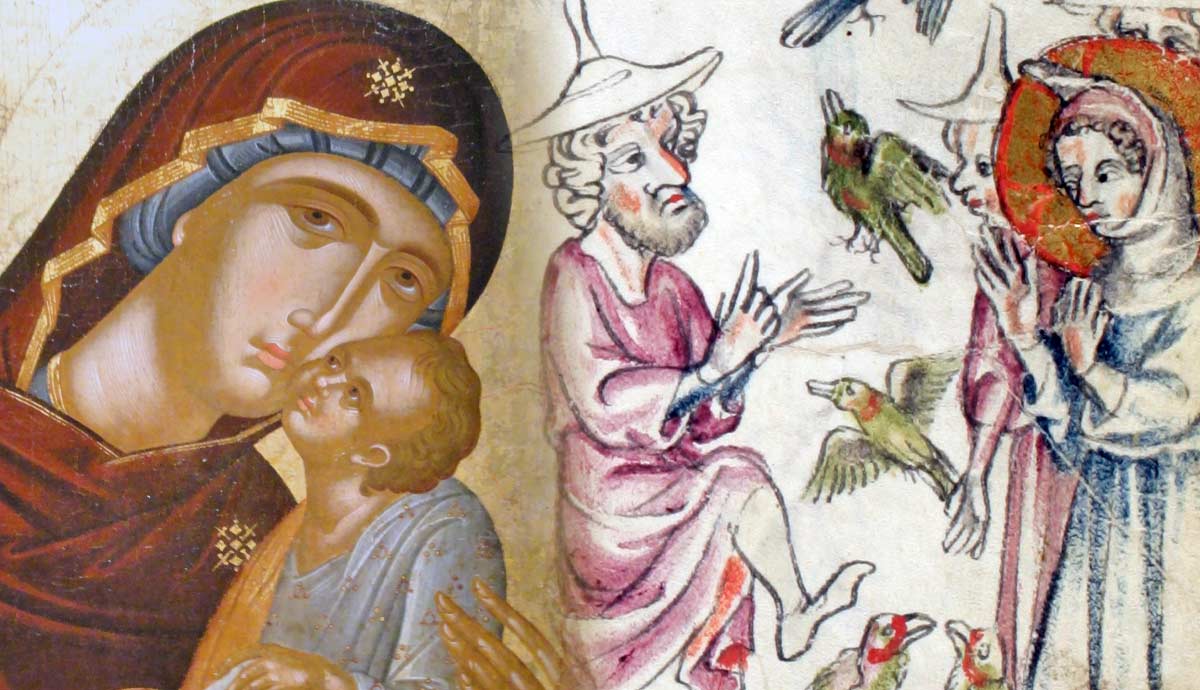

The echoes of the Book of Genesis continue in the text. In a playful moment, toddler Jesus creates twelve sparrows using water and clay. The author’s decision to begin the chronicle in this manner prompts speculation about its significance. The writer says, “and (infant Jesus) having made soft clay, he fashioned thereof twelve sparrows. And it was the Sabbath when he did these things (or made them). And there were also many other little children playing with him.”

One evident reason for this story is its resemblance to the creation account in Genesis, where God forms humans from clay. By drawing parallels between the Jesus narrative and Genesis, the author arguably aimed to make it more compelling for early Christians. However, it is crucial to note that this narrative is not included in any of the canonical gospels. In the ancient world, it was not uncommon to make parallels with other legends.

Parallels to the Gospels

After the passages that parallel Genesis, there are parallels to the gospels. The narrator recounts an incident in which a Jew observes Jesus making clay and accuses him of breaking the law of the Sabbath — as in the gospels. This individual reports Jesus’s actions to his father, Joseph, intending to cause trouble.

The text says, “[the Jew] told his father Joseph: Lo, thy child is at the brook, and he hath taken clay and fashioned twelve little birds, and hath polluted the Sabbath day.” Subsequently, the text reveals that the accuser was a Pharisee. This story aligns with the canonical gospels, where Jesus frequently clashes with Pharisees as an adult. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas appears to establish credibility by echoing stories familiar to early Christians about Jesus.

In the text, Joseph witnesses Jesus’s actions on the Sabbath and questions him, asking why he is doing things that are not permitted on that day. Jesus responds by clapping his hands together and commanding the sparrows to fly away, which they obediently do, chirping as they depart. The text states that “the Jews saw it, they were amazed.” This expression, “they were amazed,” resonates with a similar sentiment found throughout the gospels. For instance, Mark 6:51 says, “Then he climbed into the boat with them, and the wind died down. They were amazed.” In both cases, this prompted the Pharisees to leave and report the incident to their leaders. Up to this juncture, there seems to be no obvious reason for excluding it from the New Testament canon.

A Bad Fruit?

The story continues with the presence of Jesus’s father, Joseph, alongside the son of Annas, who is identified as a scribe. In this scene, the son of Annas takes a branch of willow and disperses the waters that Jesus had gathered at the beginning of the gospel. Upon observing this action, Jesus becomes angry and addresses the individual, stating, “O evil, ungodly, and foolish one, what hurt did the pools and the waters do thee? behold, now also thou shalt be withered like a tree, and shalt not bear leaves, neither root nor fruit.” Once again, there is a parallel to the gospels, in this case, Matthew 7: 17-18, where Jesus says, “A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit.”

These parallels may serve to illustrate the continuity of Jesus’s teachings, suggesting a consistent manner of expression from his youth into adulthood. Alternatively, they could be interpreted as a form of parody, wherein statements resembling Jesus’s typical discourse are employed in a manner that is not authentic to his character. Scholarly consensus on this matter remains speculative. The narrative concludes with Jesus remarking that immediately, the boy withered completely, while Jesus himself left and went to Joseph’s house. Subsequently, the story says the parents of the withered boy lifted him, mourned him, and brought him to Joseph.

A Murderous Child

The challenge posed by The Infancy Gospel of Thomas lies in its depiction of young Jesus committing acts of violence against other children. In addition to the one mentioned above, there is a second instance. Jesus reacts impulsively to a minor annoyance caused by a boy playing near him; the text says, “A child ran and dashed against his [Jesus’s] shoulder. And Jesus was provoked and said unto him: Thou shalt not finish thy course. And immediately he fell down and died.”

One can imagine that for an early theologian, what is particularly disturbing is Jesus’s apparent indifference after these incidents. Such portrayals of Jesus engaging in deadly behavior sharply contrast with the narrative presented in the canonical gospels, which depict him in the opposite manner. This opposite difference may have been provocative to early Christian readers, leading to speculation about the underlying meaning behind Jesus’s calmness and acts of violence.

Joseph’s Discipline

After the second murder, Joseph confronts Jesus about his actions, expressing concern over the suffering and hostility the children had to endure as a result. Jesus responds, acknowledging that Joseph’s words are not Joseph’s own, yet he chooses to remain silent for Joseph’s sake. Once again, one can think of a canonical parallel where Jesus says something like this to his disciple Peter.

Jesus declares that those who accuse him will face punishment, and immediately, they are struck with blindness. Onlookers who witness this event are described to be filled with fear and confusion, marveling at Jesus’s ability to turn his words into reality. Following this, Joseph physically reprimands Jesus by pulling his ear.

Esoteric Knowledge?

Jesus also has problems with his teacher, Zacchaeus. The account says that Zacchaeus attempted to instruct Jesus by teaching him the alphabet and repeating letters to him. Despite the teacher’s efforts, Jesus remains silent and does not respond.

Frustrated by Jesus’s lack of participation, Zacchaeus strikes him on the head out of irritation. This action provokes a response from Jesus, who becomes angry and rebukes the teacher. Jesus, with a bit of an attitude, responds, “Thou that knows not the Alpha according to its nature, how canst thou teach others the Beta? thou hypocrite, first, if thou know it, teach the Alpha, and then will we believe thee concerning the Beta.” This assertion, claiming a deeper understanding of mere letters, resonates with profound esotericism.

Moreover, it prompts speculation regarding the author’s intentions, suggesting an effort to portray Jesus as possessing insights beyond superficial comprehension. This would have challenged conventional authority structures in antiquity, implying that Jesus comprehends meanings beneath apparent simplicity. While his teacher perceives only letters, Jesus discerns a deeper significance.

However, this interpretation may not be immediately apparent to observers. Such esoteric knowledge, largely absent from the New Testament canon, would have presented a puzzle for early Christians to reconcile themselves with. They would have had to grapple with the image of a Jesus who commits violence alongside the one who performs miracles like raising the dead. Despite these contradictions, one can speculate on the allure of an esoteric cult in antiquity, in which individuals sought belonging and enlightenment.

Links to the Canonical Gospels

The Infancy Gospel ends when Jesus, at the age of twelve, accompanies his parents to Jerusalem for the Feast of the Passover. The writer says that after the festival, as his parents begin their journey back home, Jesus remains in Jerusalem, unbeknownst to them. After traveling for a day, they realize Jesus is missing and return to Jerusalem to search for him. After three days of searching, they find him in the Temple engaged in discussion with religious scholars. His profound understanding and ability to engage with them astonish those present.

When Mary expresses her distress at not finding him earlier, Jesus responds by asserting his need to be in his father’s house, referring to the Temple. This event showcases a link between The Infancy Gospel of Thomas and the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke. In both accounts, Jesus, Mary, and Joseph journeyed to the Temple for the Passover festival. They returned home after a day’s travel, and in both instances, Jesus was discovered sitting among the teachers in the Temple.

These parallels suggest that The Infancy Gospel of Jesus may have been written for an audience familiar with the Gospel of Luke or as a complementary text to it. Important Christian figures would continue to debate issues of canonicity for centuries to come, drawing out the lines of what is and what is not within the bounds of Christianity.