Canada can be divided into six cultural areas, and the Arctic is one of them. These regions do not have strict boundaries and therefore do not reflect political borders, either within Canada or between Canada and the United States. All of these regions have been inhabited by Indigenous peoples since time immemorial.

Today, the Inuit homelands are known as the Nunangat, and they make up nearly 35 percent of the Canadian mainland. A close look at the four Nunangat regions and their specificities will allow us to trace the history of the Inuit people back to when their ancestors, the Thule, first set foot on the land now known as Canada.

How Big is the Canadian Arctic?

Less than one percent of Canada’s population lives in the remote regions of the Canadian Arctic. More than half of them are of Indigenous descent. Overall, the High Arctic stretches from Labrador on the east coast to Yukon in the west, encompassing Newfoundland, Québec, Manitoba, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Immediately south of the Arctic is the vast cultural region known as the Subarctic. The Arctic coastline alone consists of 162,000 km (more than 100,000 miles) of snow and sea ice.

North of mainland Canada lies the so-called Arctic Archipelago, a group of 36,563 islands (with the exclusion of Greenland and Iceland), including some of the world’s largest. Baffin Island alone is larger than the whole United Kingdom, and Ellesmere is slightly smaller than Great Britain (and the tenth largest island in the whole world). The southern regions of the Arctic are defined by the tree line. Above it, lies the windy and arid ecoregion of open tundra.

The term “tundra” comes from the Finnish word tunturia, which describes a flat and treeless plain. In Canada, however, there are rugged mountains on two major islands, Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg. Today, the northeastern corner of Ellesmere Island, with its glaciers and ice caps, is a protected area.

A national park since 2000, when the territory of Nunavut was created in 1999, the name of the park here was changed to Quttinirpaaq. In Inuktitut, the language of the Inuit people, it means “top of the world.” The Inuit know how to navigate, respect, and preserve this region, just like their ancestors, the Thule people did before them.

As Joey Angnatok and Rodd Laing have beautifully written, the Inuit possess “extensive knowledge about the different types and forms of ice, how ice changes in relation to environmental factors and what changes happen during different seasons of the year.” The importance of ice to the Inuit translates into the language they speak. In Inuktitut, in fact, “dozens of different words exist to define things such as sea ice form, type, location and age.”

In most areas of the Canadian Arctic, the continually frozen ground represents a priceless open-air museum. Indigenous wood and ivory artifacts remained embedded in the ice or buried under a thick layer of frozen snow for centuries before archaeologists decided it was time to dig them up.

Before the Inuit: The Tuniit and the Thule

Bone needles, harpoons, arrows, chipped-stone tools, musk-oxen bones, ground-stone knives, and rings of oval boulders (to hold down tent edges) represent an incredible source of knowledge about the people who have lived and survived in the Canadian Arctic for millennia. This barren region has been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for more than 4,000 years after the first Tuniit people (the Pre-Dorset culture to archaeologists) expanded out of Alaska and moved eastward.

Eventually, the so-called Late Tuniit (or Dorset people) reached what is now known as the Labrador coast and finally the island of Newfoundland. In the spring and summer months, they were caribou and musk oxen hunters, living in tents made of sealskin supported by the aforementioned oval boulder rings.

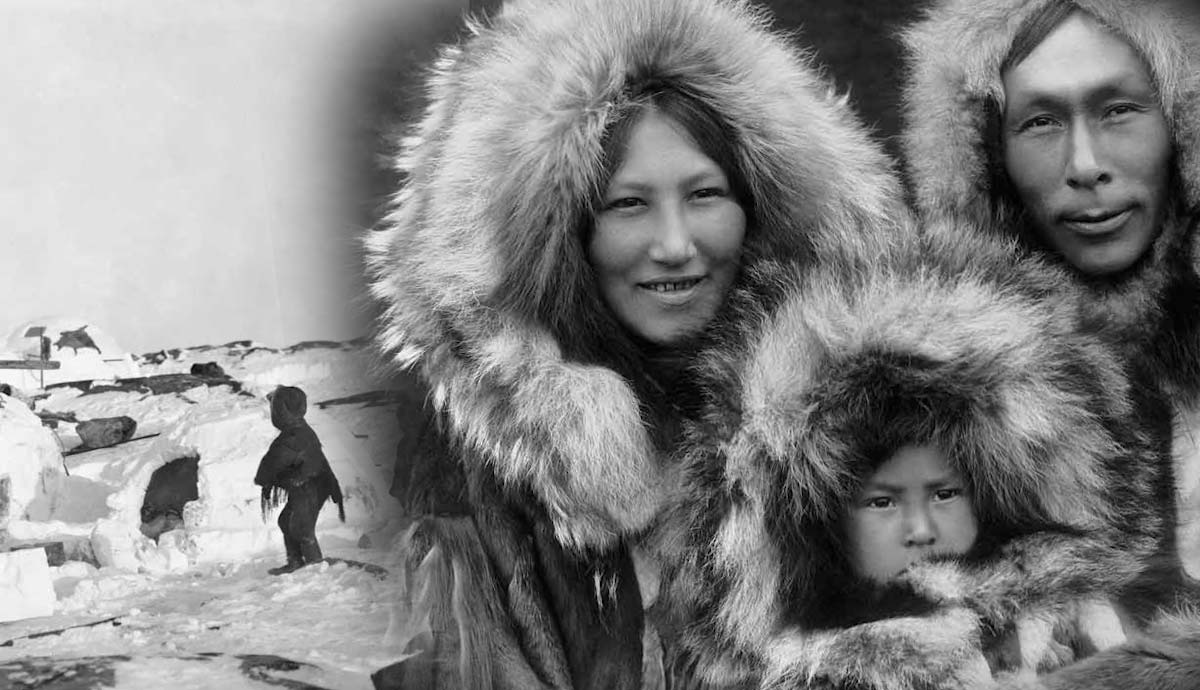

In the cold, dark winter months, they engaged in harpooning seals and walruses to survive, taking refuge in igloos and structures made of ice, sod, and rocks. Historians have been trying to define the history and demise of the Tuniit culture for decades. Some claim they were driven out by the arrival of the Thule (pronounced either “too-lee” or “too-lay”), the ancestors of the modern Inuit, who were experienced whale hunters accustomed to traveling across vast expanses of ice.

From their Alaskan homelands, they brought dogsledding and hunting boats (known as kayaks), as well as a large boat type known as the umiak, which was used to pursue whales and walruses in open water in addition to transporting goods. Their culture was richer, more sophisticated, and more technically advanced, and some historians believe that the Tuniit were gradually absorbed by the Thule.

Although the Tuniit did not survive the coming of the more advanced Thule, they have left us with some dramatic pieces of art, tiny sculptures, soapstone carvings, and wooden masks—which archaeologists believe were connected to shamanic activity. The polar bear, both an enemy and source of survival, features in many of them. Safeguarded by the ice-covered lands where they were conceived and created, Tuniit artworks have survived the upheavals caused by colonialism and are here today to bear witness to a unique culture shaped by the ice.

The Inuit and the Inuit Nunangat

The Inuit homelands are known as the “Nunangat,” a term used by the Inuit to describe the frozen waters and snow-covered lands of the Arctic region in present-day Canada. The Inuit Nunangat is a huge area that encompasses nearly 35 percent of the Canadian mainland and includes four regions

Nunavut (in Inuktitut Nunavut means “Our Land”) is a territory in its own right and includes most of the Arctic Archipelago, as well as all the islands in Hudson Bay. Nunavik, which is larger than California, lies in Northern Québec and extends into both the Arctic and Subarctic. The Nunatsiavut settlement encompasses present-day Northern Labrador, making it the southernmost region of Nunangat. Finally, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region is located in the northern Northwest Territories.

As noted in the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, “it is important to remember that shipping routes through the Northwest Passage pass through Inuit Nunangat,” thus making the Inuit people an important player in contemporary Canada. The Hudson’s Bay Company was established in 1670, and beginning in the early 1700s, a steady stream of European whalers penetrated Inuit lands, exploiting their icy waters, hunting beluga whales, seals, and sea lions.

In 1771 the first Moravian missionaries settled along the Labrador coast. By the mid-1800s, however, whalers began to establish year-round permanent stations and settlements, turning Davis Strait and Baffin Bay into the center of their whaling activity. By 1910, the whaling market had collapsed, but Inuit relations with outsiders continued. Inuit men and women became involved in the fur trade, supplying traders with beaver pelts, muskrat, bear, and white fox fur (the latter being the most prized).

European traders, however, were not the first foreigners encountered by the Inuit in the course of their long history. Before them there had been the Vikings and European explorers on their quest for the much romanticized Northwest Passage. European traders and whalers, however, most permanently altered Inuit traditions and lives.

Before the coming of European explorers, whalers, and fur traders, the Inuit relied very little on harvested foods, living almost entirely on the flesh of caribous and musk oxen (and polar bears, to a certain extent), as well as on walruses, whales, and Arctic char fish. Just like Aboriginal people across Australia, the Thule and the Inuit carefully altered the lands where they lived to work in their favor.

Not only did they build stone dams to catch the Arctic char, but the Inuit also built large inuksut, figures made of boulders and stones stacked to resemble humans. These stones function as coordination points, repositories of information about food, as well as hunting aids, driving caribou herds to strategic locations chosen by hunters and archers. A red inuksuk is found on the Nunavut flag, on a white and yellow background.

As noted by the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, the Inuit tend to reject the term “prehistory” to describe their past, because “our history is simply our history, and our oral histories stretch back to time immemorial.”

What Do We Really Mean By Inuit?

As mentioned above, the Canadian Arctic stretches from the northern coast of Quebec, Newfoundland, and Labrador in the east to the Yukon coast in the west. It is a land of treeless plains, frozen mountains, and large islands bordering Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait in the east and the Beaufort Sea in the west.

The Inuit are as varied in their history and culture as the lands they inhabit. They are not to be confused, however, with the Innu, the collective name referring to the Algonquian-speaking Montagnais and Naskapi, who have been inhabiting the northeastern Subarctic regions since time immemorial. Among the Inuit, we can identify four main groups: The Inuit of Northern Quebec and Labrador, the Caribou Inuit, the Central Inuit, and the Mackenzie Inuit.

Together, Nunavik and Nunatsiavut represent the easternmost regions inhabited by Inuit in Canada. Nunavik (in English “the Great Land”) is the term used today to describe the homeland of the Inuit of Northern Quebec. It is an immense area, covering more than one-third of Quebec’s territory. The Thule, ancestors of the Inuit, settled this vast and cold area, particularly the Ungava peninsula, around 1350 CE.

The area claimed by Inuit in Newfoundland and Labrador is called Nunatsiavut (meaning “Our Beautiful Land” in English). After decades of land claims and negotiations with the federal government, in 2006 the Inuit of Labrador (also called Labradormiut and Nunatsiavummiut) became the first Inuit to gain self-government, to have their constitution recognized and adopted, and to be represented by the Nunatsiavut Government.

As early explorers, whalers, and fur traders ventured across Québec and Labrador, the Inuit of Nunavik and Nunatsiavut were the first to see their lives altered by the impact of colonialism. Today, Iqaluit is the capital of Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory and once part of the Northwest Territories. It accounts for 21 percent of Canada’s total area and is divided into three regions: the Qikiqtaaluk (the easternmost region, which includes Baffin Island), the Kivalliq (west of Hudson Bay), and the Kitikmeot (the westernmost region, that includes the eastern parts of Victoria Island).

The Inuit of Nunavut are usually referred to as the Central Inuit, although there are several sub-groups. Unlike other Inuit, they have never been sedentary. Even before contact, they lived in igloos in winter, sleeping on platforms carved out of snow and covered with the skins of the musk oxens and polar bears they hunted.

The Inuit living in the barren interior west of Hudson Bay, in the so-called Kivalliq Region, with its miles and miles of Arctic tundra, call themselves the Kivallirmiut. For decades they have been known to non-Indigenous people as the Caribou Inuit. The term was first used by the members of the Danish Fifth Thule Expedition in the early 1920s, at a time when the caribou had already become scarce.

The Inuit encountered by the members of the expedition had already been weakened by years of food shortages and driven to the brink of extinction. The history of the Kivallirmiut is particularly fascinating because it’s still shrouded in mystery, despite several theories advanced in recent decades.

Indigenous people living in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR), the westernmost area of the Inuit homelands, insist on calling themselves “the real Inuit.” Hence their name, Inuvialuit, which means “the Real People.” Of all the Inuit groups, they are the ones who have the most in common with the Alaskan Inuit, both culturally and historically.

ISR is a remote area that stretches from the Mackenzie River Delta to the Beaufort Delta region, including Banks Island and the western part of Victoria Island. It is located entirely in the western Arctic. In its southernmost part, it borders the Western Subarctic, the land of the Athapaskan people.

The Inuit Today

For centuries Inuit were known among non-Indigenous peoples as the “Eskimo,” but the term was replaced with “Inuit” during the 1977 Inuit Circumpolar Conference, held in Barrow, Alaska. The conference was a groundbreaking moment in Inuit history, as it brought together Inuit from Canada and Alaska, as well as the self-governing Danish province of Greenland.

In English, “Inuit” means people. To date, the Inuit are one of three First Nations peoples recognized in the Canadian Constitution, the others being the Métis and the so-called Indians. According to Statistics Canada, in just ten years, from 2006 to 2016, the Inuit population grew by 29.1 percent. From 2016 to 2021, it grew to 69,7051, an increase of 8.5 percent.

As noted in the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, today the Inuit “own or have jurisdiction over half the Arctic.” This makes them “the largest Indigenous landholders in the world.” Sadly, Inuit history and culture has too often been told and studied by non-Inuit explorers, archaeologists, and linguists.

Starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Inuit have slowly but steadily regained control over their history and culture. Over the years, Inuit from all four regions of Nunangat have made their voices heard in the political landscape of Canada. Some have demanded compensation for the government’s terrible treatment of the Inuit during the so-called Inuit High Arctic Relocations of the 1950s. Others have engaged in revolutionary land claims, such as the 1984 Inuvialuit Final Agreement, the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, and the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, legal claims that have changed the way many Canadians look at Indigenous people.

The Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami has played an important role in this process. Representing 65,000 Inuit across Arctic Canada, it has been an ambassador of Inuit culture, history, civil rights, and land interests since 1971, the year it was founded.