In the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, the Canadian government manipulated several Inuit families from northern Quebec (now Nunavik) with lies and false promises into moving to Ellesmere Island, a remote island in the North. The goal was to populate the Arctic and claim sovereignty over these austere lands against the interests of the Soviet Union. Decades after the end of the colonial expansion in North America, Indigenous families were once again being displaced, relocated, and outright lied to by their government. Today they are known as the High Arctic exiles. In 2010, the Canadian government issued an official apology to the families involved in the Inuit High Arctic Relocations, finally acknowledging one of the darkest chapters in Canada’s colonial history.

Canada During the Cold War

To understand the High Arctic Relocations, we need to understand the period in which they occurred. During the Cold War, Canada was a strategic ally of the United States against the Soviet-dominated Communist Eastern bloc. The country became a founding member and proud supporter of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949. Furthermore, the so-called Gouzenko Affair of 1946, which many historians consider the official beginning of the Cold War era, took place in Ottawa, on Canadian soil. As international relations between the two blocks soured and negotiations between East and West broke down, the United States and Canada turned their attention to the Arctic.

The history of Canadian Arctic Sovereignty dates to the 17th century, to the era of explorations and the Hudson’s Bay Company. In 1880, Canada obtained ownership over this vastly inhospitable territory.

Three decades later, in 1913 the Canadian government sponsored the Canadian Arctic Expedition, which departed from Victoria, British Columbia, bound for Alaska. Led by Canadian-born Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who supervised the Northern Party, and by R M. Anderson, head of the Southern Party, it was the most expensive expedition sponsored by Ottawa up to that time. It was also a way to assert sovereignty over the Arctic.

Dozens of Western Arctic (Inuvialuit), Alaskan (Iñupiat), and Copper Inuit (Inuinnait) joined the expedition as hunters, seamstresses, and guides. Over the next decade, between 1922 and 1927, several Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) outposts were established across what is now Nunavut. Once again, many constables, unfamiliar with this rugged territory, relied heavily on the Inuit for guidance.

It was in the years from 1947 to 1953, which historians call the Cold War’s “deep freeze,” that sovereignty claims became truly paramount. The threat of a potential Soviet attack over the Ocean turned the Arctic into the distant, icy front line of Cold War rivalries.

While the United States was busy building several military bases, including the Thule Air Base in northwestern Greenland in 1951, the Canadian government implemented the Canadian Rangers. The organization had been created during the Second World War following the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 to protect British Columbia and the North against the threat of Japanese attacks. Initially known as the “Pacific Coast Militia Rangers,” it was made up of local volunteers, fishermen, and trappers.

In 1947, in the aftermath of World War II, the Canadian Rangers evolved into the organization that still exists today, composed of Indigenous peoples from many First Nations, from Inuit to Métis, from Anishinaabeg to Cree and Dene. The Canadian Rangers were the first colonial organization to consistently employ Indigenous skills and knowledge to protect colonial Canada from Cold War threats.

The Inuit families involved in the High Arctic Relocations were drawn by the colonial government of Canada into a game larger than themselves, an international game that involved nations from around the world and pitted them against each other in an intricate web of strategic economic interests.

The Facts…

Pawns. Human flagpoles. These are some of the terms used to describe the many Inuit families the Canadian government persuaded to relocate from their villages in northern Quebec (now Nunavik) to Ellesmere Island. Some families came from Inukjuak (also known as Port Harrison), a village on Hudson Bay in northern Quebec, others from Uugaqsiuvik, west of Inukjuak. Starting in July 1953, four of them were relocated to Resolute Bay and seven to Grise Fiord. Two years later, six more families moved to Resolute Bay and one to Grise Fiord. They were promised an abundance of game and fish, in what was advertised as a return to the traditional lifestyle of their ancestors. They were assured that they did not need to bring anything but food with them for a few days, because they would be provided with everything they needed.

They were also guaranteed that the relocation would be temporary, and that, after an initial period of two years, they could return to northern Quebec if they so wished. What they weren’t told was that the families would be immediately separated into three groups and relocated to different settlements, Grise Fiord (known as Aujuittuq in Inuktitut) on Ellesmere Island and Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island.

Much like the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913, the Inuit relocations represented a way for Canada to assert and solidify its presence in the North against any potential attacks by the Soviet Union as well as U.S. encroachment in the area. Although allies, tensions between Canada and its southern neighbour were high, with Ottawa repeatedly accusing Washington of making important decisions without first consulting the Canadian government.

…and the Consequences

Relocations took place throughout the 1950s, in 1953, 1955, and 1957. Larry Audlaluk (1953) told his story of being a High Arctic exile in Grise Fiord in his book What I Remember, What I Know: The Life of a High Arctic Exile (2020). His experience, though unique and deeply personal, gives us insight into the conditions the Inuit families in Ellesmere Island were forced to live in.

The relocation upended their lives. They endured extreme cold and the famous long Polar night, which most of them experienced for the first time in their lives. At Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord, summer lasts six weeks at most: from October to February there is virtually no daylight. Inuit exiles were forced to adjust to a completely different diet, learning to live with the threat of winter starvation.

The clams, berries, eggs, and Canada geese they were accustomed to were non-existent in the Arctic. Their previously balanced diet was replaced by one based almost exclusively on sea mammals, such as walrus, seals, and whales. In Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay, ice formations typically last throughout the warmer months. Therefore, fishing is much harder than in northern Quebec.

Instead of making Inuit families more self-reliant, the harshness of Ellesmere Island made them increasingly dependent on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment. It has also been reported that many Inuit huts had no heat and that the first substantial governmental services and schools were not established at Resolute and Grise Fiord until 1962. The only permanent medical facility was a R.C.A.F. nurse stationed at Resolute Bay.

Community life was virtually non-existent. The sudden and abrupt change triggered by the move had a major impact on the physical and mental well-being of many Inuit families. Far from any major center and cut off from the world they had always known, away from friends and families, many suffered from depression and anxiety. Larry Audlaluk describes how, after the relocation, his father Isakallak Aqiatushuk had become “unusually quiet, as if he were deep in thought, almost deadly silent.”

Another important account of life in Resolute Bay comes from Inuit carver Simeonie Amagoalik, (1933-2011), who was born in an outpost camp near Inujjuaq but moved to Resolute when he was twenty in 1953. Decades later, the Canadian government commissioned him, along with Looty Pijamini, to create a monument to remember the High Arctic exiles.

His son Paul was born on the C.D. Howe, the ship that took his father to the High Arctic in 1953 and the same ship on which Larry Audlaluk traveled with his father. In 2012 he recalled what his parents told him about their lives before the relocation, that “they lived in a different world, that they lived in a sustainable world, that they could live on a happy life, but when they were asked to move up here, they were told they were going to be here for only two years with an option to stay if they want, but after two years they wanted to come back down to Inukjuak but they were downrightly refused to go back.” Instead, they were if they “could convince their other relatives to come instead which happened in 1955.”

From Nunavik to Ellesmere Island

The snow-covered expanses, frozen waters and ice of the Canadian Arctic region are known to Inuit as Nunangat, which translates as “homeland” in Inuktitut. Nunangat comprises four Inuit land claim regions. One is Nunavut, which includes most of the Arctic Archipelago as well as all the islands in the Hudson, Ungava, and James bays. Nunatsiavut, in eastern Canada, stretches along the northern coast of Labrador, while the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR) occupies part of the Northwest Territories in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Finally, Nunavik (“great land” in the local dialect of Inuktitut) encompasses the northern third of the province of present-day Quebec, north of the 55th latitude, along Hudson Bay and the Ungava Peninsula. All the families involved in the High Arctic Relocations came from Nunavik, from the village of Inukjuak, known in the early 20th century as Port Harrison.

Overall, the Nunangat encompasses nearly 35 percent of the Canadian mainland, as well as several major islands. Ellesmere Island, in Nunavut, is one of them. The contrasting living conditions between Inukjuak and the settlements on Ellesmere Island had a huge impact on the lives and mental health of High Arctic exiles. Inukjuak was a stronghold of Inuit culture and traditions and a crucial community site. Over the decades, it’s been home to many Inuit stone carvers and sculptors, such as Leah Nuvalinga Qumaluk (1934-2010), Charlie Inukpuk, and Isa Smiler (1921-1986), to name just a few.

Unlike Inukjuak, Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay were a colonial product. Resolute Bay, for example, had been established in 1947, less than a decade before the relocation, as a meteorological station. Today, the sons, daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters of the first High Arctic exiles still live on Ellesmere Island. For some of them, it is home. For others, it’s a bittersweet home, the most vivid symbol of lies and broken promises from a government that was supposed to represent them. Today the Inuit still living there call Resolute Bay Qausuittuq, which translates as “the place with no dawn,” while Grise Fiord is known as Ausuittuq, “the place that never thaws.”

Ottawa Finally Apologizes

In the late 1970s, two families decided to leave Ellesmere Island and return to Inukjuak. They did so at their own expense. It was around this time that Inuit relocatees began to tell their stories of “human flagpoles,” stories that clashed deeply with the Government’s account of the relocations.

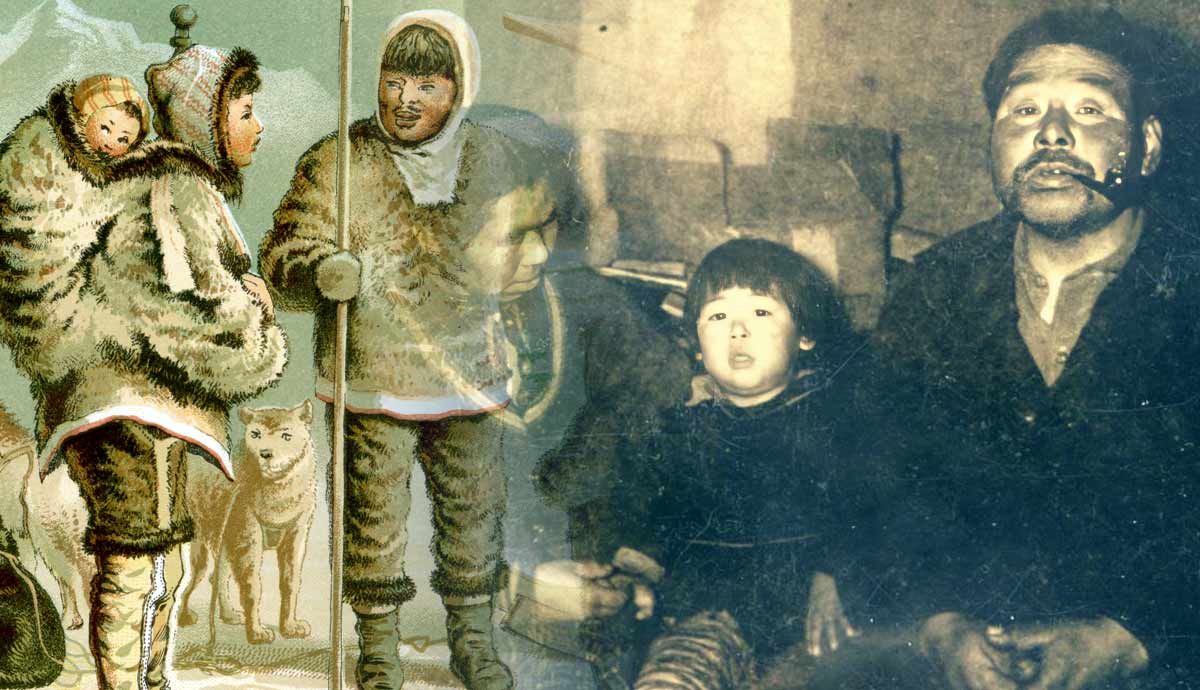

In 2008, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) chose Simeonie Amagoalik, a carver and community leader involved in the negotiations for the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, to build a statue to commemorate the relocations. Today, his parka-clad figure stands there, on the shores where Amagoalik first landed in 1953, looking south toward the Arctic Ocean, toward northern Quebec and Inukjuak. The statue’s companion at Grise Fiord was sculpted by Looty Pijamini and represents a mother and child embracing as they look south with an Inuit sled dog at their feet.

As Amy Prouty writes for Inuit Art Quarterly, the identical inscription on the plaques affixed to both statues “explicitly ties Arctic sovereignty to the actions of Inuit and their sacrifices, taking control of a historical narrative that has long been denied them.”

There is regret and resilience in these majestic and stoic figures that, along with the testimony of many relocatees and their descendants, have played an important role in the reconciliation process. Indeed, these statues are part of a long-standing work of speaking out and processing generational trauma. This process ultimately led to the establishment of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) in 1991, following the 1990 Kanesatake Resistance (Oka Crisis), and finally to the 2010 Apology for the Inuit High Arctic relocation. On August 18, less than two weeks after being appointed Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development under the Harper government, John Duncan traveled to Inukjuak.

Here, he delivered an official apology on behalf of the Canadian government to the relocatees and their families. One month later he traveled to Ellesmere Island to attend the unveiling ceremony of Amagoalik’s and Pijamini’s statues at Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord and offered these two communities two framed copies of the Apology. “The Government of Canada,” John Duncan said in his speech, “deeply regrets the mistakes and broken promises of this dark chapter of our history and apologizes for the High Arctic relocation having taken place. We would like to pay tribute to the relocatees for their perseverance and courage. Despite the suffering and hardship, the relocatees and their descendants were successful in building vibrant communities in Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay.”