During the Cold War, Central America and the Caribbean had been ripe for communist insurgencies, including Cuba, Grenada, and Nicaragua. High poverty levels and corrupt government leadership made socialism popular among the poor and disenfranchised. In Panama, the US had a longstanding relationship as a result of the Panama Canal. The Panama Canal Zone was US territory, meaning deepening tensions between Washington and Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega in the late 1980s could not be ignored. In addition to siding with the Soviet Union over the United States, Noriega was an alleged drug runner, further complicating relations. In May 1989, an election was held, and Noriega ignored the results that showed him losing, choosing to maintain office through military force.

Historical Background: Spanish Panama

When the Spanish set out to sail across the Atlantic Ocean to India, they “discovered” the New World. It did not take long to discover that the New World ranged tremendously from north to south, blocking passage across the ocean to India. In 1513, Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa discovered the Pacific Ocean, then called the South Sea, while exploring Panama. Unlike most other Spanish conquistadors, Balboa was not especially brutal and was interested in learning about local cultures. Six years after discovering the Pacific, Panama City became the first European-built city on the Pacific Coast.

Balboa’s second-in-command when he discovered the South Sea was Francisco Pizarro, who would later conquer the Incan Empire in modern-day Peru. From Panama, the Spanish began their exploration of the western coast of South America. Pizarro, having been mayor of Panama City for a time, was allowed to conquer the western coast of South America by Emperor Carlos V of Spain. Due to its central location between Mexico and South America, Panama became an invaluable military, trade, and transportation hub for the Spanish.

1819-1903: Part of Gran Colombia & the Colombia

Following the independence movements in Central and South America during the early 1800s, Panama became part of the newly independent nation Gran Colombia in 1819. Under the initial leadership of Simon Bolivar, after whom modern-day Bolivia is named, Gran Colombia included modern-day Panama, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and parts of Peru and Brazil. However, trouble soon erupted in the new nation due to social class and ethnic feuds. The relatively small numbers of Spanish settlers were unable to maintain steady power over the Native Americans, and Gran Colombia collapsed into separate nations by 1831.

After the dissolution of Gran Colombia, Panama remained part of Colombia. In November 1840, however, Panama attempted to separate itself and declared independence after years of poor economic conditions and trade disputes. The independent State of Isthmus quickly agreed to return to Colombia when faced with military invasion on the one hand but favorable terms for those who had sought independence on the other. Ultimately, Panama would remain part of Colombia for another sixty years.

1850s-1903: Pursuit of a Central American Canal

As far back as the early 1800s, traders began to consider the possibility of building a canal through Central America to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Without a canal, all shipping from Europe to Asia either had to go around the southern tip of Africa or the southern tip of South America! This took extra weeks, which was incredibly expensive and could minimize or eliminate the ability to trade disposable goods. Panama was often looked at because it was the narrowest strip of land between the two oceans, followed by Nicaragua to the north.

In 1881, the French began building a canal in Panama. Three years later, the US signed a deal with Nicaragua to pursue the same goal. However, both routes had a similar problem: the topography rose considerably above sea level in the middle of the land mass. Still, the French continued to work for eight years before stopping in 1889, stymied by high costs and worker mortality due to jungle diseases like malaria and cholera. The US had also explored Panama as far back as the early 1850s, shortly after the Mexican-American War, but quickly determined a canal to be unrealistic due to difficult terrain.

1903: Panama Becomes Independent

After the French project in Panama failed, the US tried to negotiate with Colombia to dig its own canal through Panama. However, Colombia refused the deal. In retaliation, US President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt sent Navy ships to the Panamanian coasts in a show of support for the territory declaring itself independent. Panama quickly did so and was immediately recognized as an independent nation by the United States.

US support for Panamanian independence and for intimidating Colombia against trying to retake the isthmus by force was rewarded. In exchange for $10 million and an annuity of $250,000, as well as a guarantee that Panama would always remain an independent nation, the US was given a 10-mile-wide zone of land for a canal. Within two years, construction on the American attempt at a Panama Canal would begin.

1914-77: Panama Canal Completed, Periodic Disputes

In 1914, the Panama Canal was completed and quickly changed the world of ocean shipping after its opening on August 15. The project cost some $375 million, but ownership of the Panama Canal Zone meant the US could easily allow its allies to cross from the Atlantic to the Pacific and vice versa during times of conflict. Enemies of the United States would have to sail around South America, putting them at a tremendous disadvantage. During World War I and World War II, the Panama Canal allowed the US to quickly overcome damage to either its Atlantic or Pacific Fleets by transferring ships.

However, tensions erupted between the US and Panama several times. In 1931 and 1949, diplomatic relations between the two nations were terminated briefly due to coups in Panama. In 1964, however, there were clashes between US and Panamanian troops over growing disputes regarding flying the Panamanian flag near the Canal Zone, which was officially US territory. Panama protested US control over the canal and demanded new treaties that would make the canal politically neutral. Between 1967 and 1977, new treaties were slowly negotiated, which culminated in an agreement whereby the US-controlled Panama Canal Zone would be eliminated on October 1, 1979, and Panama would take control of the canal itself on December 31, 1999.

1981-1985: Rise & Rule of Manuel Noriega

The treaties giving power over the Panama Canal back to Panama were negotiated by Panamanian leader General Omar Torrijos, who had taken control in a coup in 1968. His political ally and intelligence chief, Manuel Noriega, began taking power in 1981 after Torrijos died in a plane crash. Although other figures were the public face of government leadership, Noriega held real power as the commander of the National Guard beginning in August 1983. Under Noriega, the National Guard came to control all police and military forces under the unified Panamanian Defense Forces.

Political opponents of Noriega were allegedly sidelined or assassinated. During his early years in power, although he apparently sympathized with communist leaders like Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh, Noriega was a US ally. Beginning in the 1970s, Noriega allegedly assisted the US in keeping tabs on communists in Nicaragua and El Salvador, making him a CIA ally during the Iran-Contra Affair. However, by 1985, the friendly relationship between the CIA and Noriega began to fracture due to his alleged assassinations of political opponents.

1986-1989: Relations Fray Between US & Noriega

In September 1986, likely hoping to restore his good relations with the United States, Noriega reached out to US Marine Lt. Col. Oliver North, who was helping orchestrate the Iran-Contra Affair. Noriega offered to topple the communist Sandinista government in Nicaragua to aid the Contras in exchange for US political support. However, before any action could be taken, the Iran-Contra Affair was exposed in November. Instead of giving Noriega the opportunity to be a US ally, he was now a liability.

Since 1985, the US had been frustrated with Noriega’s refusal to accept democracy and his continued abuse of political opponents. In February 1988, he was indicted on federal drug charges. The legal leaders of Panama attempted to remove Noriega in response to the criminal charges and US pressure but were unsuccessful. In May 1989, elections were held but were declared nullified when the victors were those opposed to Noriega’s reign, with Noriega’s government blaming the “obstructionist actions” of foreigners.

1989: Planning the Invasion of Panama

The US had been looking at ways to depose Manuel Noriega since February 1988, when his drug trafficking charges were handed down. However, the situation was complicated due to the fact that 1988 was a presidential election year, and the Republican nominee, vice president George Bush, Sr., had formerly been the CIA director. Although Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis tried to tie Noriega with Bush, Bush won the election handily in November. In his presidential inauguration in January 1989, Bush declared, “the days of the dictator are over.”

With the Cold War ending, the US had free reign to act without fear of Soviet reprisal. Although Noriega had apparently been seeking Soviet support, there was little to be given in 1989 as the USSR was pulling back its troops from Afghanistan amid a crumbling economy and rising ethnic tensions. Instead, Noriega received support from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Libya. On October 3, a coup by a Panamanian general attempted to remove Noriega from power but quickly failed after it refused to hand over Noriega to US forces. Forces loyal to Noriega retook the Panamanian Defense Forces headquarters, and the coup plotters were executed. At this point, the US decided that it needed to depose Manuel Noriega by force.

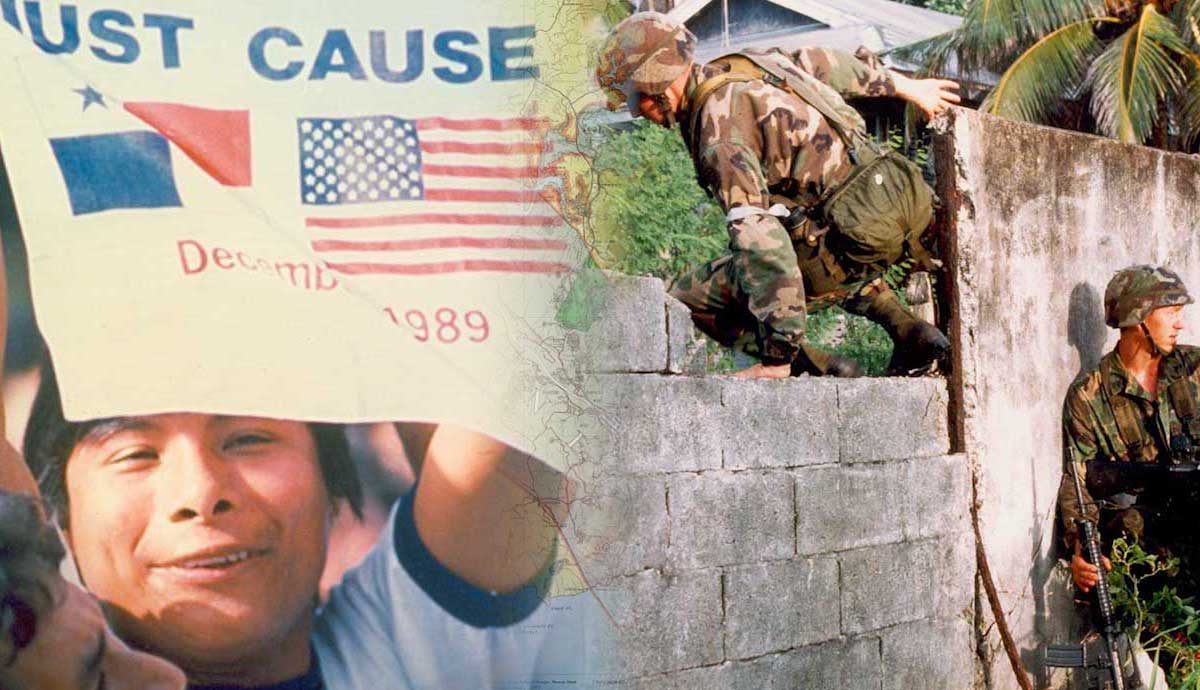

December 1989: Operation Just Cause

Unlike in 1983 with Grenada, the US had the advantage of plenty of planning time and familiarity with the target. Due to the Panama Canal, the US already had thousands of troops stationed in the country and knew it well. However, rising tensions in Panama quickly sparked the need for action. On December 15, Noriega declared that a “state of war” existed between the two countries, and the next day multiple US soldiers were attacked by Panamanian troops in Panama City. The following day, December 17, President Bush gave his approval to launch Operation Just Cause.

During the predawn hours of December 20, 1989, some 13,000 troops were flown into Panama to join an equal number of US forces already in the country. Officially, the mission was undertaken to ensure the safe operation of the Panama Canal, protect US citizens in the country, and apprehend Manuel Noriega, who had been criminally indicted by a federal court. Special forces groups simultaneously attacked multiple targets while over 1,000 US Army Rangers parachuted over key installations. Only hours later, Noriega was almost captured by a US roadblock but managed to have his driver turn around and head in the opposite direction.

The Success of Operation Just Cause

Tactically, the invasion of Panama went relatively smoothly. Despite some organized resistance, the Panamanian Defense Forces were swiftly overwhelmed by well-planned US use of air strikes, paratroopers, special forces, and armored vehicles. However, one new area of combat not experienced heavily in Grenada or in previous interventions was urban warfare. Conventional US forces, such as armored vehicles, were often vulnerable to enemy fire as they had to move slowly through a complicated urban environment in Panama City.

The strongest resistance occurred at the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) headquarters, where defenders managed to shoot down a few US helicopters. In response, however, guided missiles from attack helicopters largely destroyed the building. By 6:00 PM on December 20, the US had seized control of the PDF headquarters and destroyed all central communications of the Panamanian resistance. Noriega fled to the Vatican embassy in Panama City, which was quickly surrounded by US forces. For days, troops attempted to convince Noriega to surrender through psychological warfare by blasting American hard rock music through speakers aimed at the embassy. On January 3, 1990, Noriega surrendered.

Post-Invasion Aftermath: Noriega Imprisoned

The successful invasion of Panama and rapid securing of the country was a political victory for the United States during the waning days of the Cold War. While the Soviet Union was struggling to survive, the US had just pulled off a feat of tremendous strength and planning. Following his surrender at the Vatican embassy, Noriega was arrested and flown to Miami, Florida to face trial. Despite his arrest on drug charges, Noriega was eventually classified as a prisoner-of-war and entitled to better treatment. In 2007, Noriega briefly became the only prisoner-of-war (POW) in US custody.

In 2011, over twenty years after being flown out of Panama, Noriega was returned to the country to serve prison time. During his absence, Noriega had been convicted in Panama of several crimes, including murder. Six years later, the former dictator passed away at age 83. Today, controversy remains over the US tolerance of Noriega’s brutality and drug trafficking while he was a CIA ally, with tolerance only waning after 1984 during the winding-down of Iran-Contra.