Iran has a storied cultural history. Its roots are deep in the empires of old: the Persian Kings, Abbasid Caliphs, and the Safavid Emperors. Persian and Iranian identities morphed throughout the modern age. The culture of Iran was far-reaching and was heavily influenced by other cultures as well. Zoroastrianism and Islam served as philosophical and artistic bases throughout the centuries. However, a melding of cultures can produce conflict, and no cultural conflict has affected Iran more than the 1979 Revolution. Here are the effects of the Revolution on Iran’s culture.

Culture in Iran Before the 1979 Revolution

When the last Pahlavi Shah of Iran was installed via coup d’état by the British in 1953, it was the first of many signs that Iran was looking to the West. The Shah’s Iran would move toward secularization in an attempt to modernize. Iran was a resource-rich country with the potential to become a major player on the world stage. This, coupled with the fact that the Shah’s power was increasingly concentrated, meant that Iran was moving West, whether or not the people agreed.

The process of industrialization and modernization under the Shah’s regime looked much like it did in the 19th and early 20th centuries in Western Europe and the United States. However, one glaring difference remained in the Shah’s path to modernity: the clergy. The religious elite, several clerics, and strict Shia Muslims held office and had a considerable amount of influence in Iran. The Shah, moving not only toward a modern but also a secular government, replaced several clerics with secular officials and began creating legislation to move Iran into the modern era.

This push for modernism would come to be known as the White Revolution. Beginning in 1963, the Shah introduced several reforms that would significantly alter the culture of Iran. Land reforms redistributed plots from feudal landlords to smaller peasant families. Industrialization was a heavy focus, and thousands flocked to cities to work in factories. Infrastructure was developed, connecting Iran with modern roads. Education reform was pushed through, and the number of university enrollments rose. Women were given the right to vote, as well as to enroll in higher education, become doctors and lawyers, and run for public office.

The White Revolution was an attempt by the Shah to legitimize his rule and consolidate his power away from the traditional ruling classes. However, it effectively did the opposite. The land reforms did nothing to increase the loyalty of the peasant class to the Shah. Educational reforms and industrialization doubled the size of the intelligentsia and the working class. The White Revolution was an attempt to modernize but also to consolidate power. No amount of supposed freedom was going to stop corruption and censorship if it played in favor of the monarchy.

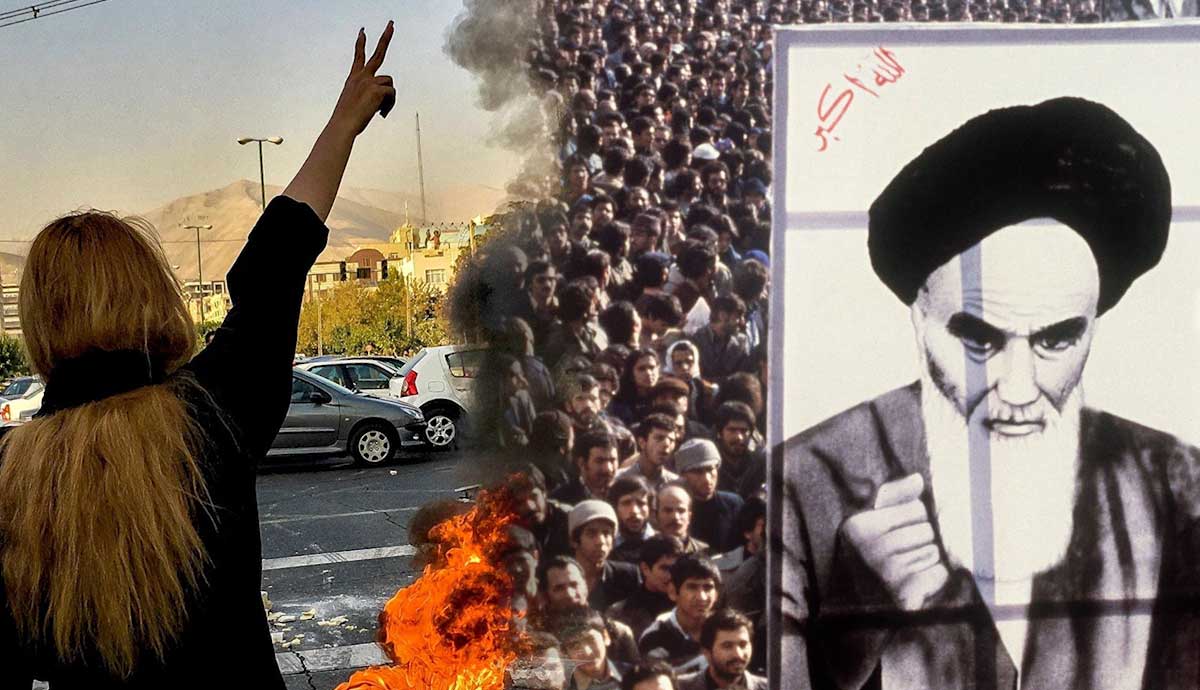

The social tension in Iran grew and was given a voice by the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. As a representative of the traditional Islamist faction of Iran, Khomeini detested and denounced the entirety of the Shah’s regime and led his followers to believe that the “Great Satan” of the United States and its allies would lead to a breakdown of Iranian culture, history, and most importantly, religion. The culture created by the Shah’s regime, though intended to modernize, never intended to allow the democratic liberties of the West. Therein lay the key to revolution. Leftists, nationalists, and Muslims alike were bound together against the Shah and set the stage for his regime to fall.

Post-Revolutionary Iranian Culture

The 1979 revolution may have seen the combined efforts of dissenters from all political persuasions to the Shah’s regime, but after the revolution, things changed. Khomeini had made himself the figurehead of the revolution under the guise that he would work with more liberal factions when in reality, he had no intention of that.

As soon as Khomeini returned from exile in February of 1979, he denounced the liberal prime minister that the Shah had appointed on his departure. Khomeini had plans of his own, with officials that would help him establish a theocracy. The Islamic Republic of Iran was established as a theocratic regime, with a government laid out in accordance with Sharia law. Khomeini appointed himself the Supreme Leader of Iran and made 12 loyalists his Guardian Council. These 13 people would have the final say over every aspect of culture in Iran, as they equated government with religion and religion with culture. There was no choice but to obey the cultural dictates of the theocracy, as disobedience to the regime was equated with disobedience to God.

Khomeini and his inner circle had, in essence, exploited the cultural aims of their revolutionary allies in the liberal and nationalist camps. When it came to running the government, there was no room for any aspect of any culture besides Shia Islam. Other cultural groups and movements were forcibly disbanded and censored. The culture was what Khomenini said it was.

Immediately, Khomeini’s government repealed all the reforms brought about during the White Revolution and suppressed the rights of hundreds of thousands of Iranians. Universities were purged of any studies relating to Western ideology, and both the National Democratic Front and Muslim People’s Republican Party were banned. Other immediate laws of the theocracy disenfranchised a religious minority, the Bahà’ís, and women.

Women and religious minorities were ousted from any positions of power they held. The legal age of marriage was lowered from 15 to nine for women, and Sharia was imposed regarding divorce, meaning a man could disown and divorce his wife for any reason. In public, men were discouraged from wearing ties and shaving their faces, and women were required to wear a head covering, preferably the chador (a full body covering).

Culturally, Iran took a sharp turn into conservatism. Suddenly, many of the liberal elements of the country that its citizens had become used to were taken away, and adherence to this new way of life was mandatory. The Islamic Republic enforced vehemence against the Western world and severely limited the freedoms that people had even under the monarchy.

Human Rights After the Iranian Revolution

Immediately following the establishment of Khomeini’s theocracy, human rights abuses began to crop up in Iran. This ranged from political opponents to women and to religious minorities. The Islamic Republic established several ways to rid itself of its opponents, all of which were legal under its constitution. The theocracy allowed brutal suppression through its interpretation of Islamic law, seeing dissidents as a threat to the structure of Islam itself. Anyone not aligned with the government was not aligned with God and was subject to punishment for their disobedience.

This began with the Islamic Revolutionary Courts and the Revolutionary Guards, who not only liquidated universities and opposing political and cultural organizations but arrested and tried the members. Political prisoners and other dissidents were held in a network of secret prisons, where they were tortured and often executed. According to Amnesty International, at least 4,000 people were executed in the years immediately following the revolution. This included minors and pregnant women and occasionally used primitive methods of execution such as stoning.

Women’s rights were severely curtailed following the revolution in an attempt to follow traditional Sharia law. In practice, this meant that women were disenfranchised, barred from over 140 higher education subjects, and prevented from working. Their rights regarding divorce and inheritance were also taken away, and they were forced to wear Islamic head and body coverings. If women were found to be breaking any of the restrictions, they would be subject to arrest and punishment, often in the form of flogging. Amnesty International reported that following the revolution, even pregnant women were flogged for breaking Sharia, and several miscarried due to the cruel treatment.

The punishment for homosexuality was also heightened under the Islamic Republic, with Khomeini calling for members of the LGBTQ+ community to be “exterminated.” This was supported by the Iranian Penal Code, which enforced harsh punishments for any sexual activity outside of Islamic heterosexual marriage. This ranged from 60 lashes of a whip to death. State-sanctioned executions of gay men began occurring regularly and haven’t stopped.

It was dangerous to be in any opposition to the government of Iran following the revolution. The state ensured its dissidents were silenced through censorship, state-controlled media, and the explicit prohibition of free speech. These severe restrictions have not stopped protestors against the cruel human rights abuses in their country, but the punishment for such actions is swift and deadly. It was and is unknown how many people have died for opposing the theocracy, but estimates put the number in the tens of thousands, as in years like 1988 alone, a minimum of 5,000 were executed.

Cultural Shifts from Post-Revolutionary Iran to Today

Immediately following the revolution, the Iranian government established an oppressive regime based on a strict interpretation of Sharia law. The culture that the Islamic Republic created was one of silence, where no one but those who were a part of the Guardianship of the Jurist (the theocracy’s official name) were allowed a voice. Despite the culture of repression, Iran’s rate of human development has increased overall, along with its literacy and education rates. Infant and maternal mortality rates have decreased, and life expectancy grew from 54.1 years in 1980 to 75.4 in 2014.

In accordance with Islamic law and to help the Islamic oppressed, the government of Iran implemented several nationalized education and healthcare plans among its people, especially in rural areas of the country. However, this development has been largely overshadowed by the intense oppression wrought by the Iranian government on its people.

The culture of Iran is one of secrecy and strict morality, according to Sharia. Shadi Mokhtari, a professor at American University’s School of International Service, says that the theocratic culture of Iran is in “social decay.” The younger generation simply doesn’t understand the fervor that their parents and grandparents had for the revolution and sees the draconian ways of the imposed culture as a limit to themselves. Protests have begun to gain significant attention within the last two decades. These demonstrations target all aspects of cultural control in Iran, from women’s dress to online freedom.

However, the government still cracks down on its perceived opponents, as in the wake of the women’s movement protests in the fall of 2022, some 19,000 protestors were arrested. Non-governmental organization Human Rights Activists News Agency states that by the end of 2022, security forces in Iran had killed at least 500 people, 69 of which were children. Women now, however, are going without hijab, especially in cities like Tehran, and are not being punished. This shift toward tentative freedom could be a positive sign and could mean that the government will attempt to ease social restrictions. The lack of transparency in the Iranian government, though, means this is unclear.

The cultural effects of the Islamic Revolution are reactionary to the Westernization imposed by the Shah beginning in 1963. However, imposing culture on people does not always last, which is why there is such social unrest in Iran today. Oppressive measures by the government to control the culture of Iran have sparked outrage and will continue to do so. The social unrest that once called for the destruction of the monarchy is now calling for the destruction of the theocracy, and only time will tell if the Islamic Revolution’s cultural shift will be upheld.