Anarchism comes in many forms, some more individualistic, others more communal. Some anarchists advocate strong property rights, others push for their abolition. What all forms of anarchism have in common, however, is their rejection of the state. In this article, we look at the major objections to anarchism, including the objections that a stateless society is unstable, undesirable, and utopian.

The Basics of Anarchism: The Ideal of a Stateless Society

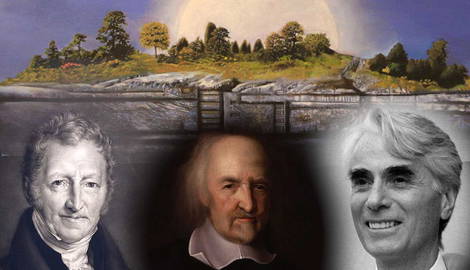

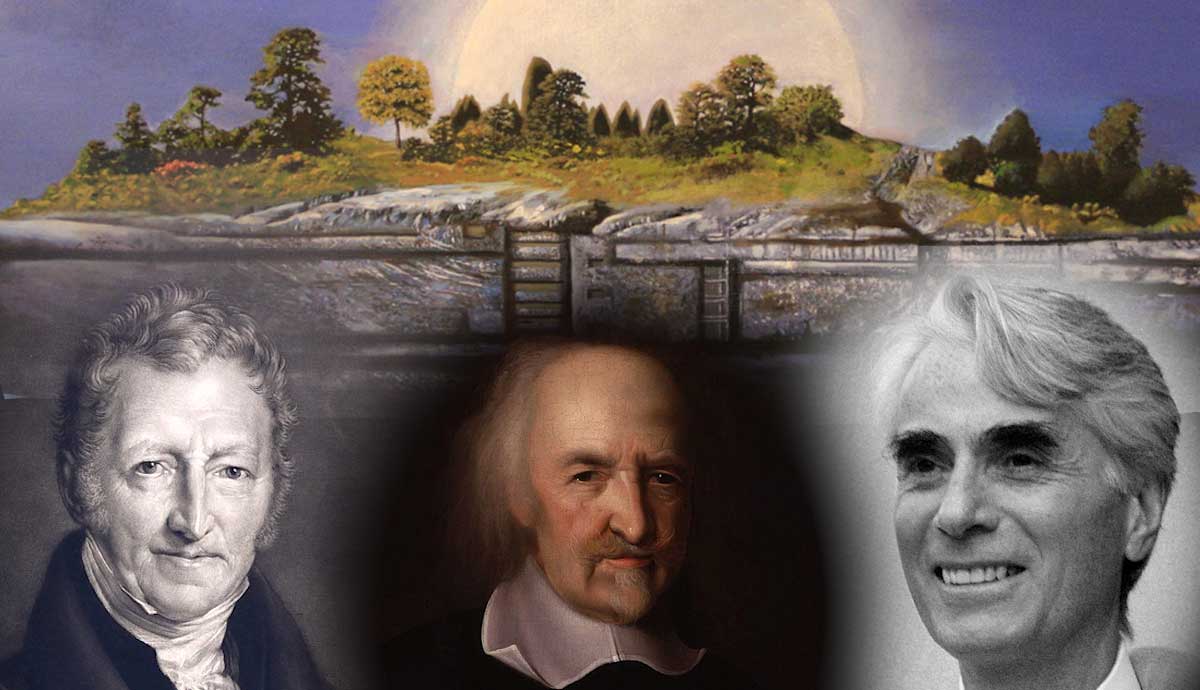

Despite their differences, anarchists all converge on one belief: the state as we know it is illegitimate and unjustified. As a consequence, we ought to abolish the state. The reasons for this belief are varied. Anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin argue that the state exacerbates economic inequality, and lends legitimacy to unnatural hierarchies of domination. Anarcho-capitalists such as Murray Rothbard and David Friedman argue the state violates people’s property rights.

All anarchists, however, hold that the state violates people’s freedom. State institutions, by their very nature, restrict our freedom by imposing obligations to obey the law (and coercing and punishing those who do not comply). Anarchism as a social philosophy seeks to free people from both the political domination and economic exploitation of the state (Kinna, 2019, p. 3).

Anarchism, like all other political philosophies, is not without its critics. Having described anarchist thought in a previous article (Anarchism Explained), in this article we will take a look at three of the major criticisms of anarchism.

Objection 1: Anarchism is Undesirable

The first major criticism of anarchism is that the stateless world anarchists describe is undesirable. Even critics who agree that the state, under current conditions, causes inequality and legitimizes domination, sometimes hold that the anarchist cure is worse than the disease: domination and inequality would be worse if there were no government.

Perhaps the best illustration of this argument can be found in Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan. Written shortly after the English Civil War, Leviathan makes the case for the importance of absolute sovereignty as a means of avoiding the harm people experience in the state of nature. Life without government, Hobbes argues, would be “poor, nasty, solitary, brutish, and short.” In a world without government, there would be none of the benefits of civilization, and people would live in continual fear of robbery or violent death. In this state of nature, the strong rule over and subjugate the weak.

The desire to avoid this state of nature is what leads individuals to create governments in the first place. In the words of Ruth Kinna, “The prevailing view is that human beings want to escape from the inconvenience or violence of anarchy and, because they have the wit to do so […] they submit to government. Anarchy is the order they run away from. It implies chaos, sometimes vigilantism, sometimes mob rule, and it cannot guarantee peace or security.” (Kinna, 2019, p. 11)

In Hobbes’ view, we can avoid anarchy through the creation of a social contract, in which individuals give up some of their freedoms to govern their lives to a sovereign in exchange for protection and the rule of law. Even if the state perpetuates inequality, it is nowhere near as bad as a state of anarchy.

Objection 2: Anarchism is Utopian

A second, related critique, is that anarchism is utopian. When anarchists are confronted by arguments such as Hobbes’s, one of the main responses is to argue that a stateless society would not necessarily be as grim as the one depicted by Hobbes. Hobbes’s argument for state sovereignty is based on taking a dim view of human nature. Hobbes conceives of people in the state of nature as inherently self-interested, willing to steal, coerce, and do harm to others in order to survive.

Many anarchists, on the other hand, take a more positive view of human nature. In Mutual Aid (1902), Peter Kropotkin brings together his expertise in zoology and social theory to argue that mutual aid and cooperation play a much larger role in evolutionary fitness than has been hitherto acknowledged. Absent government coercion, people won’t necessarily slip into a war of all against all. Instead, cooperation would be the norm amongst humans, as it is in all other areas of the natural world.

Kropotkin isn’t alone in this belief in people’s inherently cooperative nature. William Godwin takes a similarly optimistic view of human nature. Absent the limits imposed on us by the state, he argues, humans will come to see the rationality and morality of coming to each-others aid in times of need. All that is needed to achieve this is proper education.

The critique that anarchists are utopians, however, isn’t limited to their view of human nature. Their blueprints for future societies are also seen as being unachievable. Take Kropotkin’s argument for the decentralization of industry and production as an example. In Fields, Factories, and Workshops (1899), Kropotkin envisions a world in which industrial technology reduces the burden of work. In self-sufficient communities, Kropotkin describes, survival would be guaranteed by working for around 4-5 hours a day for 20 years. The key to this? Recycling organic waste and the deployment of renewable energy such as “solar, wind, hydraulic, and methane-producing installations” (Kinna, 2005, p. 121). Given that we have yet to make much progress towards these goals over a century since the writing of Fields, Factories, and Workshops, the utopian nature of the proposal seems hard to deny.

In An Essay on the Principle of Population as it Affects the Future Improvement of Society, Robert Malthus leveled similar critiques against William Godwin’s proposals in An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793). In Political Justice, Godwin also suggested that, in an anarchist world, the use of novel technologies would mean that only minimal amounts of physical labor would be required to sustain oneself, freeing people from the drudgery of work and enabling them to pursue other goals. Malthus was suspicious of Godwin’s techno-optimism, arguing that (absent strict birth control policies) the population would always expand more rapidly than our capacity to produce the food necessary to sustain it, regardless of how much we may share the fruits of the earth, making Godwin’s plan infeasible.

Anarchists disagree about whether these critiques of anarchism as utopian have any teeth. In a sense, all political theorizing is somewhat utopian in the sense that it expresses ideals to strive for. All political philosophy involves a measure of abstraction from day-to-day reality. Putting it into practice would always involve changing some of the ways we do things. This, however, doesn’t make political ideals useless. At the very least, utopian visions of the future show us the way to go. Even if we can’t achieve the plan in full, moderately utopian visions of society can help us see which aspects we can change, and help us approximate these ideals.

Objection 3: Anarchism is Unstable

The third major critique of anarchist political philosophy is that anarchism is inherently unstable. We have already considered one of the versions of this critique above when considering Hobbes’s argument for the state. In Hobbes’s view, given that a state-less society would be poor, nasty, brutish, and short, even if we could abolish the state, individuals would quickly come together to re-establish one.

Robert Nozick considers this point in detail in Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Nozick argues that both the anarcho-capitalist world described by Murray Rothbard and David Friedman and the Agorist society envisaged by Samuel Edward Konkin III would inevitably lead to the creation of state-like institutions.

Anarcho-capitalists and Agorists both argue that private enforcement and insurance companies could replace the justice functions the state plays. Instead of calling the police and taking our disputes to government courts, in a stateless society, individuals would have contracts with different private companies to insure them against the destruction or theft of their property and to enforce their rights against hostile others.

Agorists and anarcho-capitalists envision a lively market for enforcement, with a variety of private companies competing for clients by offering different rates and levels of service. The problem is the markets for protection and enforcement lend themselves to natural monopolization. That is, they are markets in which there are high barriers to entry and in which economies of scale are very powerful. In other words, the cost of protecting one individual or small group is high, but the cost of protecting an additional person is low. As a consequence, larger companies will continually outcompete smaller up-starts.

Over time, Nozick argues, we will end up in a situation in which there is only one company (or a small group of companies) that can provide these services. As a consequence, people will have very limited choice over who protects them. Although these companies may not be technically states, they will be de-facto states. The freedom that anarcho-capitalism promises thus turns out to be an illusion.

References

Kinna, Ruth. (2009) Anarchism: A Beginner’s Guide. Oneworld, Oxford.

Kinna, Ruth. (2019) The Government of No One: The Theory and Practice of Anarchism. Pelican Books, London.