Energy-dense ‘fossil fuels’ – such as coal, oil, and natural gas – are derived from fossilized organic matter. However, their combustion releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, fuelling global warming on an industrial scale. Indeed, since the Industrial Revolution, the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels have been central to the development of capitalism as a globalized economic system of production and exchange. Capitalism’s reliance on fossil fuels was established early on and has remained entrenched ever since.

Despite countless government and corporate pledges for “net-zero” emissions and a progressive transition to renewable energy, fossil fuels continue to dominate the global energy mix, with little evidence of a meaningful shift toward sustainability in sight.

When Was the Rise of Fossil Capital?

The role of energy in politics – particularly the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels – lies at the core of climate change debates. Yet, far less attention has been given to the deeper connection between fossil fuels and capitalism. From its inception, capitalism has favored “stock” energy sources like coal and oil over “flow” energy sources such as water, wind, and solar. This energy preference has shaped the global economy since the dawn of industrialization (Malm, 2016).

In Fossil Capital (2016), Andreas Malm compellingly argues that capitalism’s relationship with fossil fuels was not driven by their efficiency, but rather by the desire to exert greater control over labor. During the transition from water-powered mills to coal-fired steam in early industrial Britain, factory owners were not merely seeking efficiency, but seeking autonomy from the rhythms of nature and the bargaining power of labor. Coal offered capitalists the ability to concentrate production in urban areas where labor was plentiful and more easily exploited.

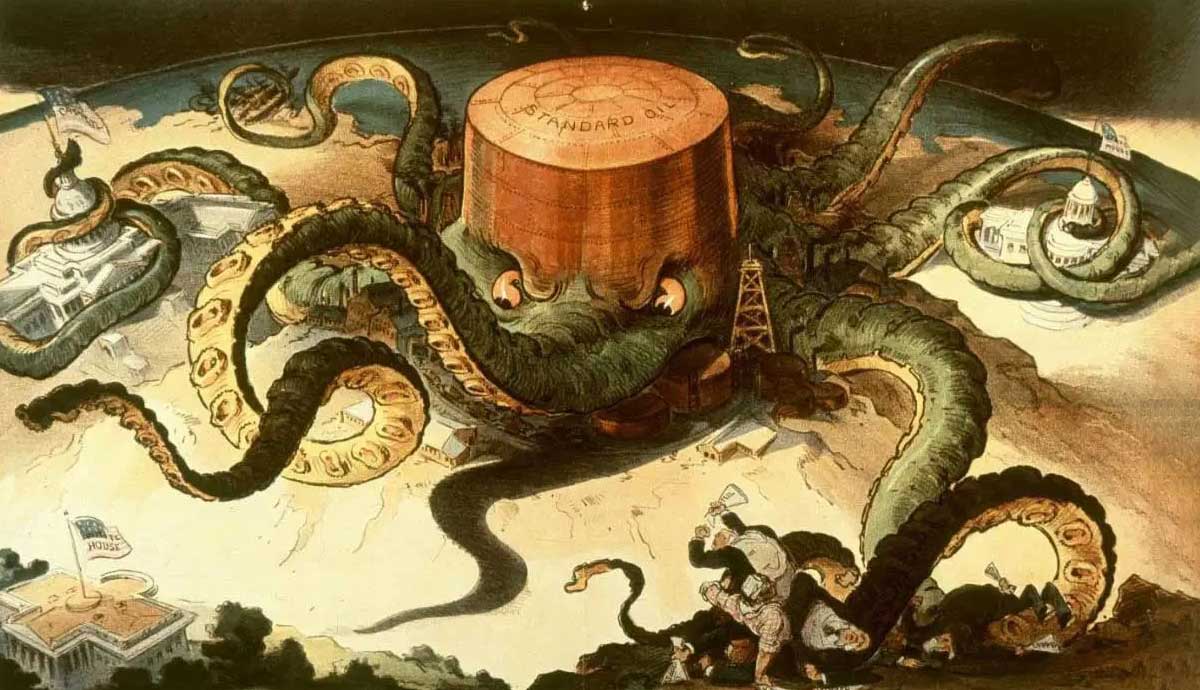

The implication of Malm’s argument when it comes to the contemporary politics of climate change is to shift the blame for the climate crisis away from consumers and towards the producers – namely, capitalists. This requires looking beyond a narrow focus on “big oil” to examine the broader economic system that transforms fossil fuels into inputs that power the massive infrastructures of industrial production, transportation, and consumption that comprise the global economy (Huber, 2017).

When Did Global Fossil Fuel Consumption Begin?

While Fossil fuel use dates back to the Industrial Revolution, the scale and nature of consumption have evolved dramatically over the past 200 years. Initially, coal dominated industrial energy use, powering steam engines, factories, and railroads throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The late 19th century saw the rise of a more versatile and energy-dense alternative – oil. After the development of the internal combustion engine outpaced steam demand for petroleum soared. By the mid-twentieth century, oil became the dominant global energy source.

Following the development of long-distance pipelines and advances in liquefaction technology in the latter half of the 20th century, natural gas became a viable fossil energy source. While It has lower carbon emissions than coal and oil, natural gas is mainly methane (approx 90%) – the second largest greenhouse gas contributor to global climate change after carbon dioxide.

Despite recurring international pledges to “transition away” from fossil fuels, proposed by governments and at successive UN Climate Change Conferences (COP), the 2024 report of the Energy Institute (EI) reported that with global temperature increases averaging close to 1.5, 2023 was the hottest year on record. Coal, oil, and natural gas comprised 82% of the global energy mix. Greenhouse gas emissions from energy use, industrial processes, flaring, and methane (in carbon dioxide equivalent terms) increased by 2.1% to exceed the record level set in 2022. Talking about “transition” as underway in this context is misleading.

Is There Such a Thing as Green Capitalism?

If capitalism is the leading contributor to carbon emissions and both corporations and the global economy at large remain dependent on fossil fuels – it follows that corporations have a responsibility to invest in efforts to mitigate climate change. Breaking fossil fuel dependence in favor of renewable energy is not just an ethical imperative but a necessary step to save the planet.

In this light, advocates of ‘Green Capitalism’ argue that the maximization of profit and environmental sustainability can harmoniously co-exist. In response to dire warnings and political pressure, capitalist markets have been positioned as the best solution to impending environmental crises (Carney, 2021; Bloomberg & Pope, 2017; Sachs, 2008).

Green capitalism encompasses a variety of market-driven strategies, from carbon emissions trading schemes like ‘carbon pricing’ and ‘carbon bonds’ to investment in technological innovations, such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, and (as yet non-existent) carbon capture technologies (Fox, 2022).

Governments worldwide are increasingly committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, following the return of Donald Trump to the White House, the United States – the most powerful state actor in the global economy – has signaled support for fossil fuels and the desire to roll back clean energy initiatives.

In light of the relentless pursuit of growth that defines the global economy a pressing question emerges: is capitalism capable of saving the planet, or is it the force driving its destruction?