Something The Mona Lisa, David, and The School of Athens all have in common is they represent a way of thinking that was shaping and being shaped by the visual arts of that period. From the 14th through 17th century, Italians looked backward to move forward, finding much inspiration in the values of Classical philosophy, art, and ways of life as a foundation and complement to their own principles of individualism, secularity, observation, and the natural. These values are visually represented within several Renaissance motifs characteristic of art from this period.

Greco-Roman Mythology and Technique in Italian Renaissance Motifs

One of the pillars of Renaissance humanism was a renewed interest in Classical antiquity, a period understood by Renaissance thinkers as representing some of the highest values of humanity—critical thinking, rhetoric, and an emphasis on the individual. Even the definition of Renaissance, although not used until the 19th century by a French intellectual, implies a rebirth of culture. According to Renaissance humanists like Francesco Petrarch, the first birth of culture took place in Classical antiquity. Writing in the mid-1300s and therefore somewhat biased, Petrarch saw the period immediately before him as blanketed in darkness, lacking culture, creativity, and development. Petrarch was actually the one to assign the period preceding the Renaissance as the Dark Ages. Petrarch and his contemporaries, such as Dante Alighieri, paid tribute to Classical poetry and philosophers in their creative projects through references to Classical writing styles, most famously the three-part play structure of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

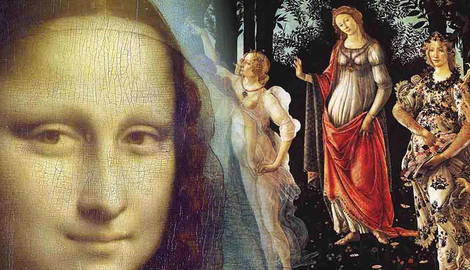

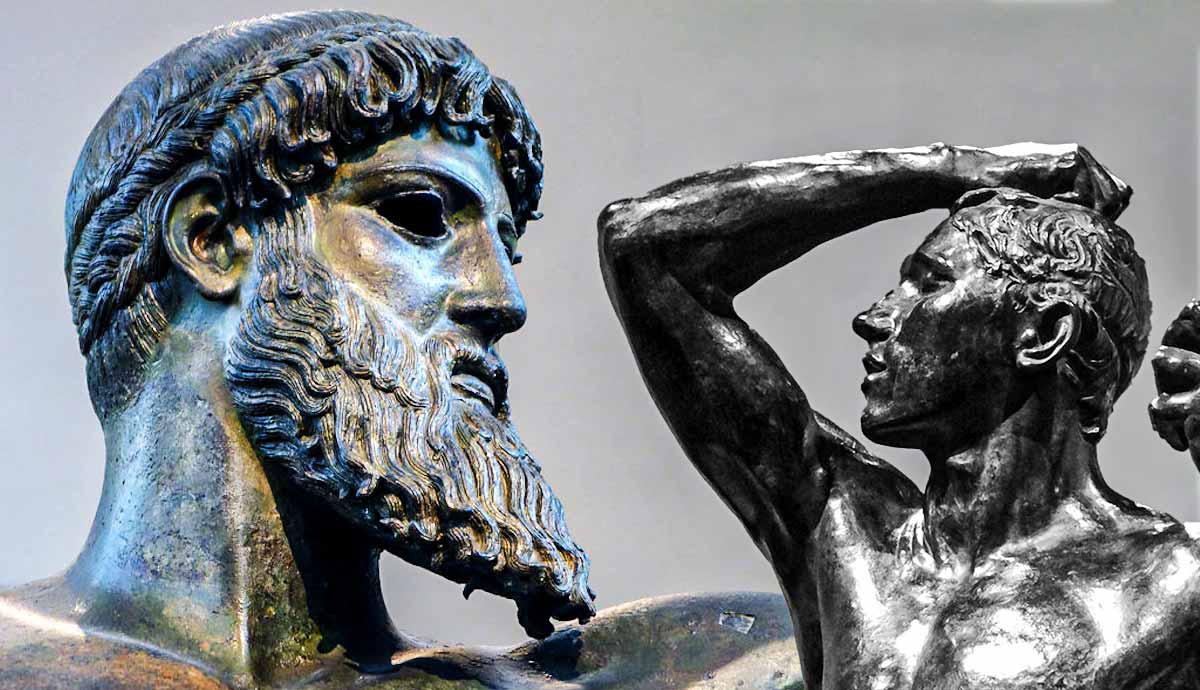

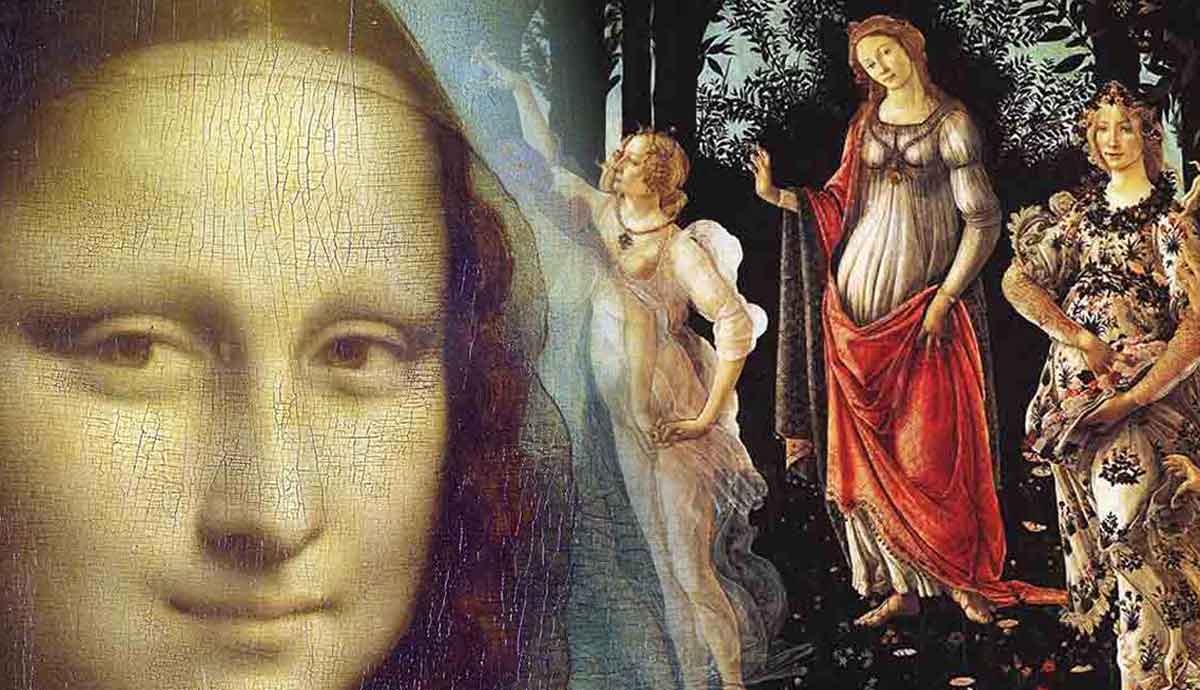

In addition to serving as a blueprint for their own values, antiquity also played a role in establishing a new or revived visual language. Thematically, this was represented by the use of Greco-Roman mythological figures and narratives, such as Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, a depiction of a Romanized version of the Greek Aphrodite. Humanists saw a philosophy in the Greco-Roman visual pursuit of proportion, realistic anatomy, and balance. These values reflected the humanist appreciation of the individual.

In The Birth of Venus, Botticelli directly references Greco-Roman sculpture through his use of contrapposto, creating balance and realism in the human form by placing most of the body weight onto one leg. The female figure on the right also references Greco-Roman sculpture through its realism—the appearance of her legs under the folds of her dress being caught by the wind reference Greco-Roman sculptures such as The Nike of Samothrace. Compared to the stylized art of the European Medieval period, which concerned itself more with the content and message of art than mimicking life, artists in the Renaissance were driven to create art, especially the human body, as a direct replication of life. Other Renaissance works of art such as Michelangelo’s David reference Classical antiquity in both content and style and provide an example of this Renaissance motif.

Portraits in Renaissance Motifs

Renaissance portraiture didn’t begin with The Mona Lisa but was a gradual development shaped and formed by centuries of changes in technique, materials, and tastes. The rise of portraiture in the Renaissance has a two-fold nature. Portraits reflected the values of Renaissance humanism alongside economic changes that allowed wealthy families to commission their own paintings. Prior to the Renaissance in Europe, most art was commissioned by the Catholic Church.

Thematically, most art portrayed biblical narratives, characters, saints, and martyrs. However, developments in trade and banking created an opportunity for individuals to accumulate their own wealth and thus commission works of art separate from the umbrella of the Church. It is worth mentioning that even during the so-called Dark Ages, Europe was a part of a mosaic of trade that spread from the furthest points of East Asia to Europe via the Mongols. In fact, this transcontinental connection created the conditions for the Black Plague to spread in the first place. Infected rodents would hide within the clothing and personal items of the Mongols and were brought to stopping posts along the intricate network of the re-opened Silk Road.

Florence, the seat of the Italian Renaissance, first grew as a wool-producing city involved in a network of Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade during the Middle Ages and later gained its prominence through a revolutionized banking system using a double-entry book-keeping of debits and credits first developed in Genoa. This system became the basis of wealth for many individuals who would become patrons of art during the Renaissance, such as the Medici family. Empowered by new wealth and inspired by the humanist fascination with the individual, patrons of art in the early period of the Renaissance began asserting themselves into commissioned works of art while remaining true to biblical themes. They were not the main subjects but participants in the narrative taking place.

As time progressed, patrons became increasingly included in art production, eventually becoming the sole subject matter. Roman portrait busts heavily influenced Renaissance portraiture, and further influences of Classical style are the use of a side profile to reflect the portrait style of Roman coins. Technological developments such as oil paint by the Flemish were tools in the Renaissance painter’s tool kit, the slow-drying properties of which allowed the creation of layers of detail and depth.

In the early Renaissance, portraits of women were typically “commissioned by the husbands to celebrate marriages, [which] memorialize[d] the brides’ domesticity, piety, and above all, chastity,” as Yiyuan Xue writes. This would be conveyed through the inclusion of clearly religious objects such as prayer books, rosary beads, and covered hair. This was transformed in the 16th century by The Mona Lisa, which represented a revolution in portraiture that became a blueprint for succeeding portraits.

Firstly, there is a breakdown of the distance between the sitter and the viewer facilitated by the direct gaze of Lisa Gherardini, the speculated woman in this portrait. Paired with the lingering smile on her lips is the awareness that she’s being looked at. In such a dynamic, she is an active participant in the gaze of others rather than a passive individual, the norm for earlier Renaissance portraits. Another revolutionary technique was a purely natural backdrop, a reflection of the Renaissance humanist concern with the natural world.

Furthermore, although Gherardini is most likely a woman from a wealthy family, she isn’t depicted with the trappings of wealth and splendor like other portraits of women from this same period. Xue writes: “Taken together with the Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, perhaps Leonardo wanted to emphasize the quality of his sitters’ individualities rather than being byproducts of their husbands and families’ social status.” This style influenced many others following it, such as Raffael’s Maddalena Doni.

Flora in Renaissance Motifs

Realism and naturalism in representations of the human body and nature constituted the humanist relationship to the external world. There was an increased interest in the study, replication, and understanding of plant and animal species in the Renaissance that owed a large part of its foundation to medieval botany. Botanical studies prior to the Renaissance provided detailed information regarding plants for medicinal purposes, sometimes affiliating certain plants with religious symbols, such as the three-leafed clover as a symbol of the Holy Trinity, which could be used to protect against snake bites, an obvious reference to Eve and the serpent of humanity’s corruption. Furthermore, some meanings assigned to certain species of plants were Catholic adoptions from the Greco-Roman period, most notably Bacchus or Dionysus, the Greco-Roman god of wine famously affiliated with grapes, a character revived in visual art by Renaissance artists.

Botanists have identified around five hundred species of plants and flowers in Sandro Botticelli’s La Primavera. The exact purpose of this painting is unclear, but there is a theory it was a wedding gift from a member of the Medici family, a hypothesis strongly supported by the visual symbols of flora depicted. From the species identified, Michele Busillo, in referencing the book Botticelli’s Primavera: a Botanical Interpretation Including Astrology, Alchemy and the Medici with the First Color Reproductions of the Primavera Since its Restoration by Mirella Levi D’Ancona, notably mentions the strawberry plant, hyacinth, rose, iris, and violet, all of which have affiliations with love, pleasure, fertility, and desire.

From the thread of branches reaching out of Chloris’s mouth on the right is a strawberry flower, recognized by its marigold center with ivory petals extending outward. Chloris was a nymph captured by Zephyrus and transformed into Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers depicted to her immediate left. More strawberry flowers pepper the ground by Flora’s feet and decorate her crown. Strawberries across cultures are symbolic of fertility, sensuality, love, and marriage due to their ruby color, sweet flavor, and spring blooming. Furthermore, in Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art, Simona Cohen writes that citrus fruits were often affiliated with the virtues of the Virgin Mary: “In Marian iconography citrus fruits were often interchangeable as symbols of chastity, salvation and redemption. The orange blossom was the flower of the bride and the lemon, as a symbol of fidelity in love, was also connected with nuptial themes. The iconography of the Virgin under a lemon or orange tree in Venetian Renaissance painting seems to have influenced secular depictions of love in nuptial contexts.” In La Primavera, Venus, the Roman goddess of beauty, fertility, and love, is centered under a canopy of citrus fruits and is stylistically represented with the visual attributes of the Virgin Mary, a dual acknowledgment of her virtues visually and symbolically through the plants.

Animals as Motifs in Italian Renaissance

In the introduction of Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art, Cohen argues that many of the Renaissance depictions of the natural world were extensions of symbolism from the Middle Ages. Taking influence from Medieval bestiaries, animals were embedded with human qualities or assigned values that conveyed specific virtues. Oftentimes, a single animal could represent opposing values “such as good and evil, virtue and vice, sacred and profane or birth and death.” The peacock symbolizes immortality and resurrection but also pride.

Further, specifically within Renaissance paintings, the inclusion of a peacock was a symbol of eternal life. Cohen states they were often depicted in Renaissance nativity scenes, but they can also be found in portrayals of the Adoration of the Magi, such as the work by Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi. In this work, the peacock sits directly on top of the barn, the tips of its feathers hanging directly above the newly born Christ, entwining the message of eternal life between the bird and the child.

Doves are also a recurring animal in European religious art. Typically included in annunciation scenes near white lilies, they were considered honorable and trustworthy. They were considered faithful because they mated once and remained widows if their mate died. Further, Annunciation scenes, including a dove in flight, are symbolic of the Holy Conception.

Ermines were a symbol of purity and incorruptibility. One of the most well-known depictions of an ermine is from the portrait Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo Da Vinci. Although there are many layers embedded into the possible meanings of the inclusion of the ermine (references to Hercules, the names of both the sitter and her lover, or references to the sitter’s pregnancy), Leonardo Da Vinci in his own bestiary, mentioned the “purity” of the ermine: “The ermine out of moderation never eats but once a day, and it would rather let itself be captured by hunters than take refuge in a dirty lair, in order not to stain its purity.” Da Vinci’s inclusion of this animal could be a reflection of personal biases and understanding of this animal.

Artwork from the Renaissance is a rich mosaic of visual messages that have become lost to the 21st-century viewer. However, for someone from that period, the visual links between plants, animals, and figures were mostly likely understandable references. It is important to rediscover these messages to help bring these works of art to life and better understand the context of the art itself, why and how it was made, and for whom.