The Rastafari movement is known worldwide for its symbolism and music. Oftentimes, however, the philosophical virtue and complexity of this religion-turned-philosophy is overlooked. Concepts like I & I, livity, or Zion and Babylon are essential for the wider Rastafari movement and provide the cornerstones for their ontology. This ontology, or worldview, is shaped and reproduced through their Iyaric language; a language so sophisticated that some of its concepts can be brought in direct conversation with philosophers like Plato and Spinoza.

The Rebellious Origins of The Rastafari Language of Iyaric

Of course, language or other forms of communication shape the worldview of all and anyone. However, it is not often that a language is consciously shaped in order to align with the worldview. In the Rastafari movement, this was actually what happened. Iyaric is a consciously formed language that originated in the 1960s. It is formed in such a way that it objects to oppression while promoting freedom and community among all, making it a direct representation of how the community wants to live.

Before diving into the actual language, it is good to stress why the language was consciously ‘invented.’ This has to do with the core tenets of the movement, which relate back to colonial times. These revolve around oppression. Because of colonial oppression, Rastafari live in a non-conformist way, without apology—both through their language and their actions. The main conviction is that language can do harm, not only to someone’s feelings but through reproducing narratives that are harmful for communities worldwide. Hence, the language of the colonizer should be avoided at all costs. Or rather, the aim is to avoid deceptive practices of systems and violent powers that reproduce the colonial narrative.

It is no secret that these marginalizing pressures continue to this day, and the Rastafari aim to resist them at all costs. They simply don’t want to conform to the world that has been detrimental to them for such a long time. Therefore, they are transformed through a “renewing of the mind.” In order to renew the mind, Rastafari focused on the language that formulates the thoughts in this mind. A quote from Bob Marley’s ‘Redemption Song’ indicates the essence of the movement; ‘Emancipate yourself from mental slavery.’

Iyaric or “Dread Talk:” The Language of Rastafari

In the middle of the 20th century, Iyaric emerged in Jamaica. Also referred to as ‘dread talk’ or ‘Rasta talk’, the language is a standalone way of speaking, which incorporates influences of English, Amharic, Jamaican Patois, and biblical references. The name is also based on the nature of the movement, whereas it is derived from ‘I’ and ‘Rasta’.

Amharic, the Semitic language of Ethiopia, is incorporated because of the tight relations between the Rastafari movement and Ethiopia—a country that is often referred to as Zion by Rastafari. This relation is mainly expressed through the recognition of Haile Selassie I—the former Ethiopian Emperor—as either a god or as the representation of Pan-Africanism and overcoming colonial oppression.

How Does Iyaric Resist Colonial Oppression, and What Is Its Cultural Significance?

The Iyaric language is a unique blend of words and symbolism. Iyaric has a pretty recent but interesting history. After the start of the slave trade, English was imposed as a colonial language on the people of Jamaica, forcing them to lose their traditional African languages. With the rise of the Rastafari movement, a modified language started to emerge with the aim of liberating their language from its history. By doing so, it recognized the language of the colonizer as a tool of colonial oppression. While physical slavery was perhaps abolished, the ‘mental slavery’ continued, mainly through using the language of the colonizers.

In order to overcome the oppressive element of the English language—which, again, was also an influence for Iyaric—all the connotations that implied oppression had to be taken out. And that’s exactly what happened; words like ‘back’ were removed and substituted for more positive ones.

It should be noted, however, that Iyaric is not a standardized language and can take on various forms among different Rastafarian communities and individuals. However, standardization is not the point of Iyaric. Life is various, permeable, and subject to change all the time. Therefore, a language representing this should be too. In fact, Ilyaric purely serves as a means to express Rastafarian beliefs, spirituality, and cultural identity. Because of this, it is opposed to becoming a fully ‘developed’ language for purely communication purposes.

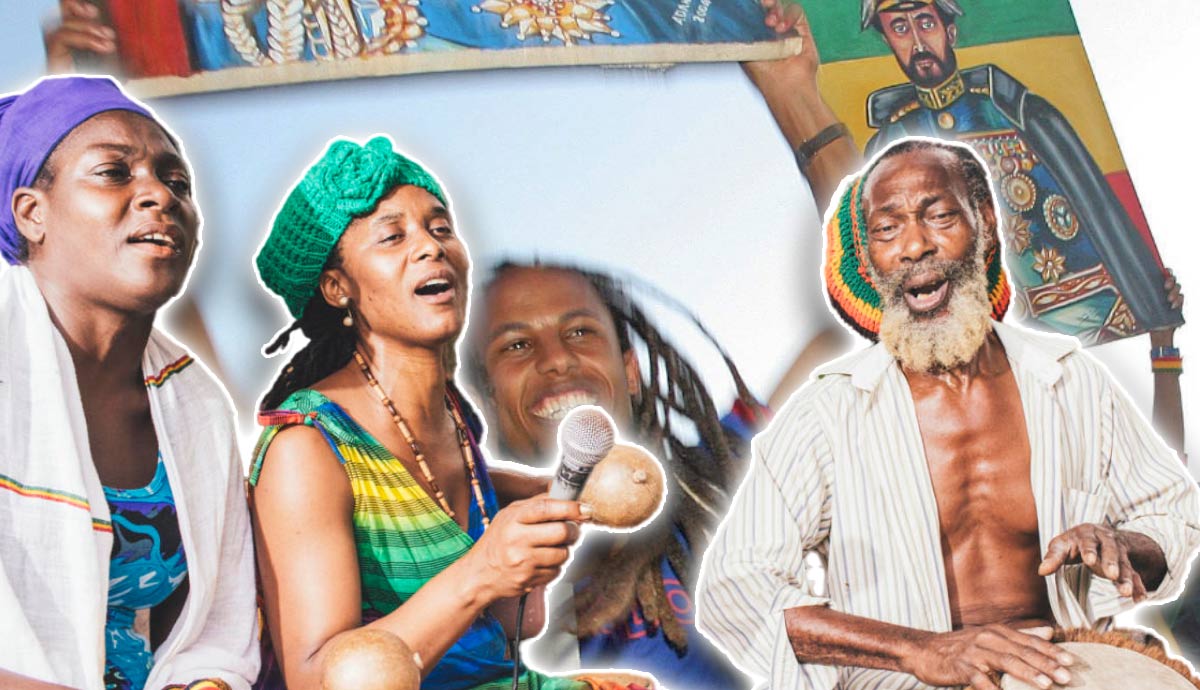

Because Iyaric is literally built to overcome oppression, it carries cultural significance. Naturally, Iyaric serves as a marker of Rastafari identity and solidarity, reinforcing a sense of belonging in the Rastafari community. Rituals, prayers, chants, and music all use Iyaric to express the struggle of oppression and the sharing of love and solidarity. Rastafari believe that the vibrations of speech and music impact our world in both the physical and social sense. By adjusting word-sounds to more harmonic ones, the goals of the movement are better reflected.

Harmony in Language: I and I, God, and Community

One of the most poignant differences between Iyaric and English is in how they view the individual; in Iyaric, ‘I’ replaces ‘me.’ The latter is said to objectify the person in question, whereas ‘I’ emphasizes the subjectivity of the individuals.

This also extends to the community and the world around you. One of the most prominent and prevalent manipulations in Iyaric relates to ‘we’ and ‘us.’ Because it is believed that community is abstracted from ‘the self’ through these words, an overfocus on the individual would be automatically promoted. To indicate your shared common essence in relation to the spiritual, Iyaric uses I and I (or I&I, InI) instead of ‘we’ or ‘us.’ It is a complex term and expresses the concept of oneness between two persons and beyond. In the original sense, I and I means that Jah (or God) is in all men—indicating that under this eternal recognition, we are all one.

The Importance of the Divine in Rastafari Philosophy

It is important to note that the ‘I’ in ‘I and I’ extends beyond the divine Jah. In Rastafari, the ‘I’ collides with community, nature, and the divine. While divinity and philosophy have a weird and complex relation, the Rastafari movement predominantly started out as a philosophy and religion at the same time. Its very beginnings can be traced back to Marcus Garvey—a prominent philosopher from the Harlem Renaissance. However, not long after the original writings of Garvey, Haile Selassie I came to be seen as a god, emphasizing the divine essence of the movement. Still, Haile Selassie I is considered to have been a living god by Rastafari, who unfortunately died in the mid-1970s.

Because of this, the religious nature somewhat vanished and isn’t as evident anymore today as it was before. This also leads to the fact that people began to see and treat Rastafarianism more as a philosophy. Either way, the divine remains part of the everyday talk and actions of the movement and is therefore represented in some of its most essential concepts.

I and I at the Center of Rastafari Philosophy

Now that we know why the divine is named in relation to philosophy, the idea of I and I can be further explored. Through the collision of ‘I’ with the aforementioned realms, ‘I’ becomes reinforced as first person singular or plural. The ‘I’ proliferates outward and synthesizes the empirical and the metaphysical. This echoing outwards is also reflected in dub music and the echoes and sirens used therein—indicating that the movement also recognizes sounds as vectors of philosophical concepts.

I and I does not only connect the ‘I’ to its surroundings, but it also affirms and empowers the speakers through multiple levels of agency. For one, there is collective empowerment. The collective consciousness and sense of unity embodied through I and I give individuals the agency to get and remain in contact with the wider community.

Secondly, the individual gains a sense of spiritual and philosophical agency. The terminology enables the individual to embody the application of Rastafari philosophy in daily life, as well as the ritual practices, allowing it to express Rastafarian principles.

Thirdly, through being connected with the wider world and community, an element of self reflection opens up. It allows individuals to assert their place within the community and in relation to their spiritual connection.

Lastly, I and I describes the synthesis of the observable world with the non-observable worlds. Therefore, it allows people to bridge the gap between the material and the non-material world through beliefs and practices.

All in all, through using I and I, the person is allowed to think about and act on (1) their role in the community; (2) the role of the community in their own life; (3) the practical activities that help to enforce these roles; as well as (4) the balance of tangible and intangible realities.

The Place of Iyaric in Wider Philosophical Debates

While the philosophical virtue of Iyaric extends beyond I and I, the concept is definitely one of the most prominent ideas within Rastafarianism.

As should be evident, the essence of Iyaric is to overcome the oppressive structures that are found in the language of the colonizers. For these reasons, the Rastafari community might resist their concepts being discussed in Western philosophical terms—which is a very legitimate point. However, just to indicate how profound some of these terms are, some scholars argue that InI can easily be placed in dialogue with the work of Plato or Spinoza.

The modus operandi of many philosophers or academics is to actively avoid this inclusion. However, in that case, the concepts found in the Rastafari movement are placed as inferior to the aforementioned philosophers, with little reason for doing so. Only after recognizing the importance of distant philosophical schools of thought and juxtaposing them with the ‘Western’ philosophies, bottlenecks in our current way of relating found in national and international endeavors can be laid bare and acted upon.