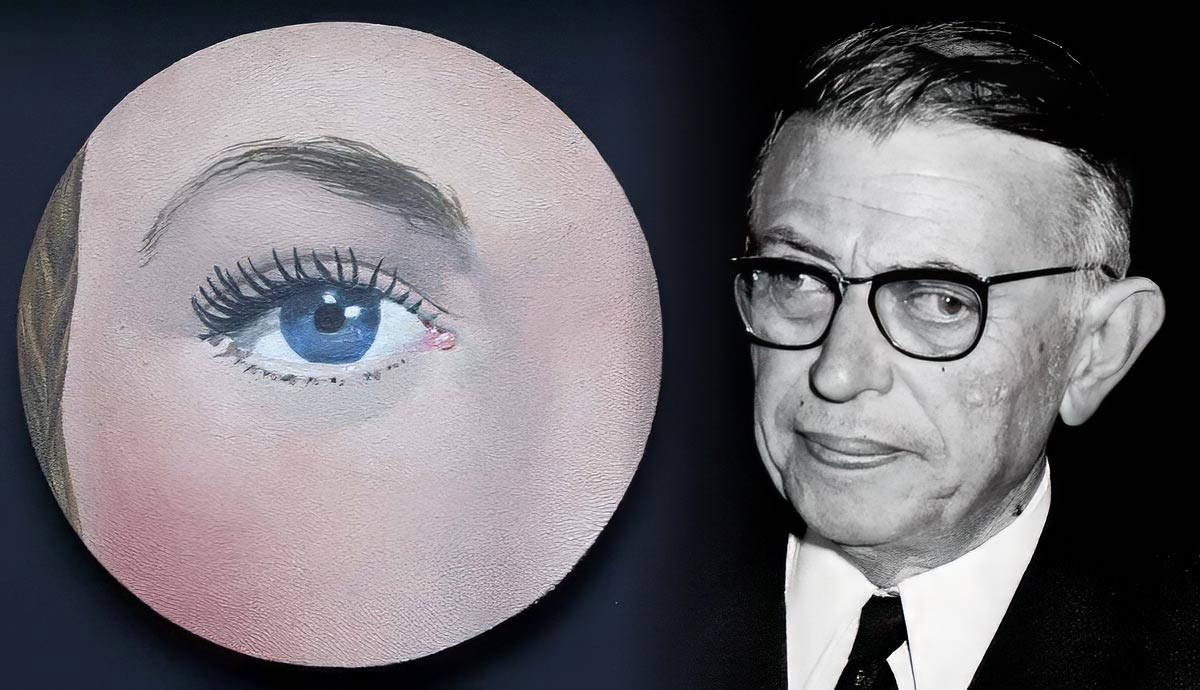

This article will examine Jean-Paul Sartre’s argument for how our human reality is riddled with interpersonal conflict, which can, paradoxically, be both enslaving and liberating. We must live with other human beings, but they can also be our greatest threats, which leads him to conclude that hell is other people—but it isn’t all bad. Certainly, the importance of philosophizing about our relations with other human beings cannot be overly emphasized.

The “Look”: Objectification According to Sartre

Imagine yourself staring at a stranger, say, in a restaurant. Then imagine a different scenario in which you notice someone else doing this to you. How do you feel and react in each situation? As Sartre argues, the presence of others inevitably changes our world, and the fact that we cannot change nor always control that can be very frustrating. The ways in which others alter our worlds vary, but what is always the case is that we cannot avoid some form of relations with others.

In the first scenario, Sartre argues that we must wrestle with the fact that this other person, by analogy, must have a subjective mind like me, but we are forced to only infer this because that other person exists in the realm of objects. We cannot get into their mind. Thus, we struggle to recognize their subjectivity in the face of their seeming objectivity.

In the second scenario, the tables are turned, and we may feel objectified by the look of another. This “look” as Sartre refers to it (which need not be literal, as simply imagining how others can look and objectify us is enough to alter our sense of self), is the source of meaning that we get from our relations with other people. This experience can be especially alienating in certain situations.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

As Sartre demonstrates, imagine you are alone in a park, but after some time, another person arrives. They need not be near you or even notice you, but the presence of another person alters your experience in the park. But without any judging looks from that other person, the impact on the self is not felt deeply.

In another example of Sartre’s, we can see how the impact can, conversely, be felt very intensely; that of his famous “voyeur” case. Imagine peering through a keyhole at someone else in this scenario. The other person does not know you are watching them, so they are completely objectified for you, by you, and you are completely absorbed in the activity of doing so and thus are not very aware or reflective of your own subjective self.

Next, imagine you suddenly hear footsteps—now, you become very aware of your self. In fact, you feel objectified by the other who sees what you are doing and judges you, creating a feeling of shame for having objectified another—now you know how the other person on the other side of the door would feel if they knew they were being watched.

This phenomenon is so powerful that you can be shaken into this situation even if you just thought someone was approaching as you looked through the keyhole. In this case, your sense of self has been deeply affected: as Sartre says, the Other “holds the key to [your] existence” because now this third person who has arrived has the power of a subject because they have objectified you (or so it seems). A cat, for instance, catching us peering through a keyhole would probably not have the same effect on our sense of being a shamed self. Thus,

“Hell is—other people!”

“Hell is—other people!”

This infamous line of Sartre, “Hell is—other people!” comes from No Exit, a one-act play with only three characters who are literally in hell as recently deceased individuals forced to interact with one another. They immediately begin to experience conflict. As they get to know one another, Garcin, an intelligent but disloyal man, comes to be attracted to Inez, a stern woman who loathes him, and instead is attracted to Estelle, who is described as a very beautiful young woman who is attracted to Garcin—nobody wins. They each, as an “other,” constrict one another’s freedom.

Toward the end of the play, Garcin declares:

“So this is hell. I’d never have believed it. You remember all we were told about the torture-chambers, the fire and brimstone, the ”burning marl.” Old wives’ tales! There’s no need for red-hot pokers. Hell is—other people!”

In other words, there is no physical torture that awaits them: it’s the emotional and mental torture of having to relate with other humans that makes that place hell (which, in its description throughout the play, resembles the real world).

Our relationships with others are, therefore, inherently conflictual. We all want to be in control, and that by nature equalizes us, yet we still fight against that reality. When we are caught staring through the keyhole, we can also stare right back at that third person and make them the object. However, we can only do that if they are a subject because only a subject has the power to create an object (or again, so it seems). At times we may feel trapped in the gaze. This can manifest in many ways, some of which are particularly nefarious and discriminatory.

In his book, Antisemite and Jew, Sartre expounds on how it is the gaze of the antisemite that creates the Jew; an unjustified form of discrimination. A similar theme was further developed by another existentialist-leaning philosopher and psychologist, Frantz Fanon, applying this idea to the black colonial experience in Algeria in the middle of the twentieth century regarding how the colonialist creates the colonized, and the racist creates the erroneous category of being inferior—these are not natural categories if we are all free subjects.

Existentialist Simone de Beauvoir argued that women’s place in the world has always historically been that of the object to the subject of man. In other words, this objectification occurs not just with individuals, but also with groups of people and thus can result in all forms of discrimination.

This “othering” is problematic in other important ways. This is what condemns love to failure in Sartre’s view because we can never fully control the ways others see us though this is precisely what we expect in romantic relationships; to be seen in a specific beloved way. Love is the attempt to control objectification.

Indifference to othering does not work either, because we can never be completely apathetic, and we simply cannot live without others. Indifference to othering is also inherently contradictory because, in the attempt to deny the existence of the other, we deny the existence of the self. Even worse, when we use hatred as a response, thinking this is a way to control the gaze of the other, we just push even more negativity into the world. Moreover, hatred is inherently contradictory as well because we must recognize the other person with significance to hate them. For Sartre, therefore, it seems as though we cannot win: we are always doomed to conflictual relations with others.

Sartre’s View: Both Pessimistic and Optimistic

While Sartre’s view may seem highly pessimistic and ultimately cynical, there are also some important elements of optimism. The fact that all humans are really subjects means we are all equal. To be respected as a subject, this must come from another subject; so, for one to be free, we must all be free.

A central creed of Sartre’s existential thought is that we are radically free. This is also the root of Sartre’s pivotal notion of “bad faith,” which is precisely denying this; again, when we deny the freedom of others, we are refuting that for ourselves as well. The problem, however, is that we can never have a complete intersubjective understanding with another human being; naturally, we cannot ever get inside the consciousness of another.

This is one reason, for instance, we constantly fear being misinterpreted by others. We can approach this fear with certain people over time, such as with close friends and significant others, but never arrive at complete understanding. We try to control the look or idea of the look of another, but we cannot fully, so the human world seems to be a cycle of constant conflict that we can never extricate ourselves from.

Sartre on Breaking the Cycle of Conflict (Through Equality)

Is there any hope of getting out of this cycle? Maybe not, but at least pondering how we relate to one another enables us to progress, albeit to an unknown extent. It is part of a great paradox, which is why Sartre says things like that we are “condemned to freedom,” which is why we have no fixed nature and thus “existence precedes essence.”

We cannot live without others, not just for obvious survival reasons, but because we can only be fully recognized as a subject by another subject, even if we constantly reject the subject-hood of others when we objectify them. In other words, we are contradicting ourselves by negating the radical freedom and subjectivity of others, because in doing so, we deny this for ourselves as well. So, within this existentialist thought, there is also the argument for the reality of equality that exists between every human being.

Sartre’s lifelong friend (and, for a time, significant other) Simone de Beauvoir posited that “The category of the Other is as primordial as consciousness itself.” Is there any way to escape othering? Can discrimination be overcome if we cannot stop othering? Are we our own worst enemies? These certainly remain problems. These are exceedingly important topics to discuss, which highlights the importance of continuing to revisit existentialist philosophy.