Joan of Arc, or Jeanne d’Arc, as she should really be called, strikes as a powerful figure of national identity in France. Famous for inspiring the French to ultimate victory over the English during the Hundred Years War, she is seen as the embodiment of French courage and dogged determination.

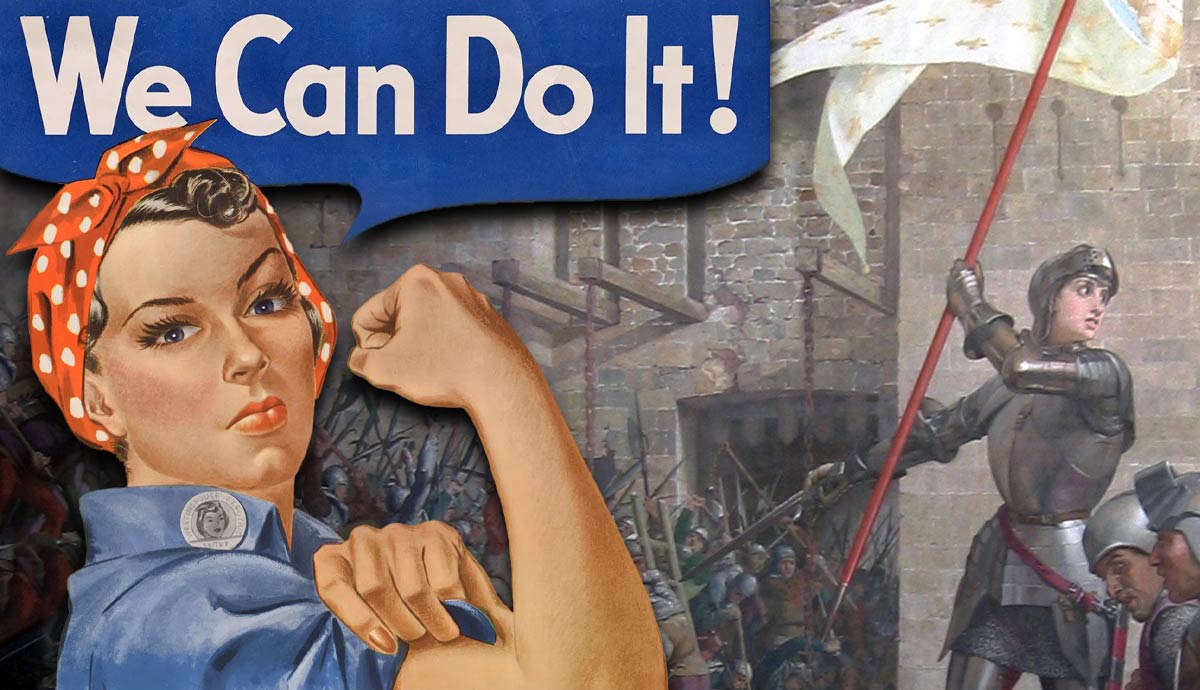

She was just a teenager when she accomplished all her incredible feats of national resolve. For this reason, she stands as one of the earliest examples of feminine strength. Born into a world where women were relegated to footnotes in history if they were lucky, Joan of Arc destroyed the preconceptions of what women were capable of. Thus, she has become a powerful icon for feminist movements in modern times.

A Very Brief Summary of Joan of Arc’s Life

In 1412, Joan of Arc was born into the life of a peasant in the town of Domremy in northern France. Hardship and the threat of violence were close neighbors as France was at war with England, and northern France had become a lawless place with marauding armies in search of victory and plunder.

Her early life was nothing particularly different from other peasant families. She looked after animals and did chores around the land on which they lived. Her mother taught her to sew and instilled in her a strong sense of piety. Joan took to religion fiercely, and it guided her actions for her whole life.

A few years after she was born, Henry V of England launched a major campaign against France and inflicted a heavy defeat on the French armies. It was eventually agreed that he would be granted the throne upon the death of Charles VI, the reigning French king. Both kings, however, died in 1422, and the French, seeing an opportunity to put a French monarch back on the throne, made preparations that would lead them once again into conflict with the Kingdom of England. Charles VI’s son, also named Charles, was backed to become the next king.

Around this time, Joan of Arc began seeing visions of angels. She claimed to have been instructed by Saint Michael and Saint Catherine to be the savior of France. They told her that she was to seek an audience with Charles in her mission to install him on the throne and rid France of its hated enemies.

Her attempt to contact Charles was not an easy one. She contacted Robert de Baudricourt, the garrison commander of the town of Vaucouleurs, but he initially refused. Without official backing and the means to travel to Chinon, where Charles held court, Joan’s mission was impossible.

The refusal did not deter her. In 1429, the following year, she spoke with Baudricourt again. Upon realizing her following, he gave her leave to visit Charles along with a military escort.

Not only did Joan identify Charles when he was dressed incognito in a crowd of people, but upon meeting with him, she revealed details of a prayer he had made to God in his younger days. The clergy were summoned to examine her, and they concluded that she was no charlatan.

At the age of 17, Joan was outfitted in armor and given a horse. She was to accompany the French troops under siege from the English at the city of Orléans. Her presence inspired the French to victory, and her fame spread across the realm.

With Joan at his side, Charles traveled to Reims, where he was crowned Charles VII. The war was, however, not over, and Joan was needed on the battlefield to inspire the French troops.

In 1430, she was captured by the Burgundians, who sold her to their English allies. She was put on trial. Her accusers had a difficult time proving her guilty of heresy. She was knowledgeable and honest in her response to the lengthy questioning. During her entire time in captivity, she held herself with dignity despite the threat of torture and rape (although there is no evidence that either occurred).

The verdict, however, was a foregone conclusion. She was convicted not just of heresy but of wearing men’s clothes and burnt at the stake in Rouen on May 30, 1431. She was just 19 at the time.

After her death, a retrial was ordered at the behest of Charles VII, and Joan of Arc was cleared of all charges against her. She was beatified around 500 years later, and in 1920, she was made a saint.

Saint Joan of Arc is the patron saint of France.

A Feminist in Her Own Time?

The proto-Feminist author Christine de Pizan, who lived at the same time as Joan of Arc, celebrated the heroine as a feminist symbol. De Pizan was a poet, already an unusual occupation for a woman at the time. In her poem “The Tale of Joan of Arc” (Le Ditie de Jehanne d’Arc), she describes Joan’s miraculous feats as being attributed to her being a woman.

De Pizan is also famous for her work “The Book of the City of Ladies” (Le Livre de la Cité des Dames), in which she celebrates the lives of famous women from history.

Joan in First Wave Feminism

Although the “wave” terminology is subject to criticism in that it focuses on Western models and timelines, what is considered the First Wave Feminist Movement began in 1848 with the Women’s Rights Convention and ended in the first half of the 20th century. Although it was characterized by the demand for political equality, it was also a fight for general recognition in many other spheres of society.

The movement drew inspiration from women throughout history, including the notable women who fought during the French Revolution. This connection with French women would stretch back to include Joan of Arc, who would become a powerful feminist icon.

In 1867, Sarah Moore Grimké, a prominent American suffragist, translated a biography of Joan of Arc into English and introduced the version as being particularly relevant to equality for women.

While hailed today, the movement for women’s suffrage was ridiculed by large sectors of society during its time. The fight was difficult and, at times, punctuated with tragedy. As early as 1909, Joan of Arc was adopted as a literal poster girl for the suffrage movement, especially in Britain, where the movement was particularly strong.

In 1913, Emily Wilding Davison, a suffragette, placed a wreath of flowers by the foot of a statue of Joan of Arc, which looked out over the Suffragette Fair and Festival in Kensington in the United Kingdom.

Joan’s militant nature, her humble beginnings, and the obvious fact that she was a woman who fought made her a convenient icon for the suffragette movement, which was noted for its more militant style as opposed to the pacifist style of the suffragist movement that came before.

A few days later, Davison was trampled under the hooves of a horse belonging to King George V while she tried to attach a Suffragette flag to its bridle at the Epsom Derby. She died from her injuries and became a martyr to the cause. At her funeral service, a woman named Elsie Howey dressed as Joan of Arc in a full suit of plate armor while riding a horse.

Around her, others held banners aloft that repeated words attributed to Joan of Arc, “Fight On, and God Will Give the Victory.”

This was not the first time the image of Joan of Arc had been used in a march, and it would not be the last either. Saint Joan’s Alliance, a suffragette organization, was founded in 1911, and a woman dressed as Joan of Arc became a trademark of their marches.

It was, however, Elsie Howey’s portrayal that would garner much media attention, as it was related to a public death that had been witnessed by thousands of people and was already a huge news story. Later on, Elsie Howey would continue to provide the same spectacle in other feminist marches.

Joan of Arc was already a popular figure in the United States and had served mainly as a source of patriotism since just after the Revolutionary War. The fact that she was French seemed to matter little. What was important was her fight against repression and foreign occupation, which resonated with the American public. Already established in the public conscience, she was an obvious choice as an icon for feminism.

The fight for universal suffrage in the United States mirrored that of its British counterparts. Inez Milholland was one prominent figure who, dressed as Joan of Arc, led a march of 8,000 women in 1913 at the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson.

Joan’s rise in popularity was not just as a feminist icon but as a national icon too. In 1909, she was beatified, and in 1920, she was made a saint. However, these two ideas of what Joan of Arc represented were seldom in conflict in the public mind. It is only through academic inspection that the historical figure versus the modern interpretation gets put under the microscope.

Joan was a firm supporter of the Catholic Church as well as the French Monarchy, two institutions that were heavily characterized by patriarchy. Thus, the question remains whether Joan of Arc would have condoned the suffragist or suffragette movements.

Despite this dynamic, however, Joan of Arc created in herself the ideal of a feminist, whether she realized it or not. She was strong-willed and independent. She responded to her interrogators with rhetorical questions and showed marked intelligence. She even wore her armor to her trial. She was the complete antithesis of what a woman was expected to be at the time. Centuries later, she still struck the same image in a societal dynamic where little had changed, and women were (and still are) repressed.

Joan of Arc dressed as a man. She cropped her hair short and fought on the battlefield. Stepping out of the traditional role envisioned for women, she paved the way for women to be able to step out of their confined gender roles and take part in society in ways that only men had been privileged to do. Her actions inspired women to be powerful, demanding the right to vote, take part in male-dominated sectors, become politicians and businesswomen, be educated as equals, and choose their own destinies. She probably had no idea how feminists in the future would draw upon her for such inspiration.

Nevertheless, there are opposing critiques. The fact that Joan of Arc was successful was partly due to the fact that she acted as a man. This dynamic can be seen as championing masculinity rather than celebrating femininity. This critique relies heavily on gender roles and what femininity and masculinity are supposed to be. Needless to say, the arguments are complex, and justifications can be found everywhere.

Perhaps Joan would have identified more with her image in Ireland, where the fight for equal rights became linked with the struggle for freedom against British oppression. War against the English was, after all, at the center of her life. Hundreds of women joined the ranks of their male counterparts in Ireland and fought in the rebellions and uprisings. Joan was a perfect fit for the fight for Irish independence. Naturally, the fact that she was a woman was a convenience for the feminist movement that could not be ignored.

One of the co-commanders of the Easter Uprising was Constance Georgine Markievicz, who went on to become the first woman elected to the Westminster Parliament and, thus, the first woman in Europe to be elected to the position of cabinet minister or the equivalent.

Markievicz was a feminist with significant power and used the image of Joan of Arc to promote the cause. She famously appeared at a suffragette fundraiser dressed as the French heroine.

Through the successive feminist waves, Joan of Arc would hold her position as a representative of women and women’s rights. Both men and women would use her image to spur women into action. One such example is the use of her image to encourage American women to buy war savings stamps.

Joan of Arc on the Silver Screen

The constant reinforcement of Joan of Arc as a feminist icon, as well as a historical figure, was made possible not just through the actions and promotions of her by feminists but also by popular culture, which created a near-constant stream of media dedicated to the French heroine.

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century, there have been numerous portrayals of Joan of Arc in cinema. Like the Joan of Arc in first-wave feminism, her legend inspired movements and ideas that exceeded her limits as a figure of French nationalism. She was readily adopted and lauded by other cultures who saw the value in her story.

Much of this had to do with the fact that she represented a strong female figure. A representation enjoyed and encouraged by both men and women in today’s society.

From short documentaries to full-length feature films, Joan of Arc has been the subject of inspiration in many cultures. The 1913 Italian production Giovanna d’Arco tells the story of Joan’s life and was one of the first films to do so.

Joan was not just confined to being represented as a subject for documentary-style films. She was used as a character far removed from the faithful retelling of her life. In the 1916 film Joan the Woman, an English officer in the First World War experiences a vision of Joan of Arc and ends up reliving her story in his own way.

Throughout the decades, her story would be told and retold in various languages, keeping her memory and relevance alive to the very present. The epic The Messenger (1999), directed by Luc Besson, is one such film with an immensely high profile, starring Milla Jovovich, Dustin Hoffman, John Malkovich, and Faye Dunaway.

However the films tell her story, and whatever aspect they focus on, is not as important as the fact that her legend is kept alive. Her place as a feminist icon is already established, and any depiction of her reminds people of that fact, no matter what the depiction is.

A Modern Joan of Arc

Throughout the modern era, women in different countries who rose to prominence in their fight for freedom have been labeled as their country’s Joan of Arc. There has been an Afghan Joan of Arc (Malalai of Maiwand), a Vietnamese Joan of Arc (Triệu Thị Trinh), a Polish Joan of Arc (Emilia Plater), and many others. These titles may be problematic because they stem from a Western perspective of why these women are relevant. Calling these people “The Joan of Arc of…” does, however, give Western audiences a valuable perspective on their place in history.

Joan of Arc has become a sort of “gold standard” icon for women fighting against oppression. Her name has evolved into a byword for women who fight.

In some instances, this clashes with the French nationalist idea of Joan of Arc, where her legend is used to promote ethnic pride. In 2018, in the annual commemoration play in Orléans, a teenager with Beninese and Polish heritage, Mathilde Edey Gamassou, played Joan of Arc and received heated criticism from France’s right-wing demographic.

For modern audiences, however, the medieval France that Joan fought for is mostly immaterial. Her legend has transcended that period of history and has evolved to suit the needs of modern society.

One of those important needs is equality, and in a world that is inarguably patriarchal, Joan of Arc will be the eternal representative of feminist action.