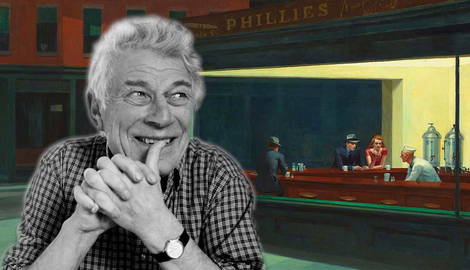

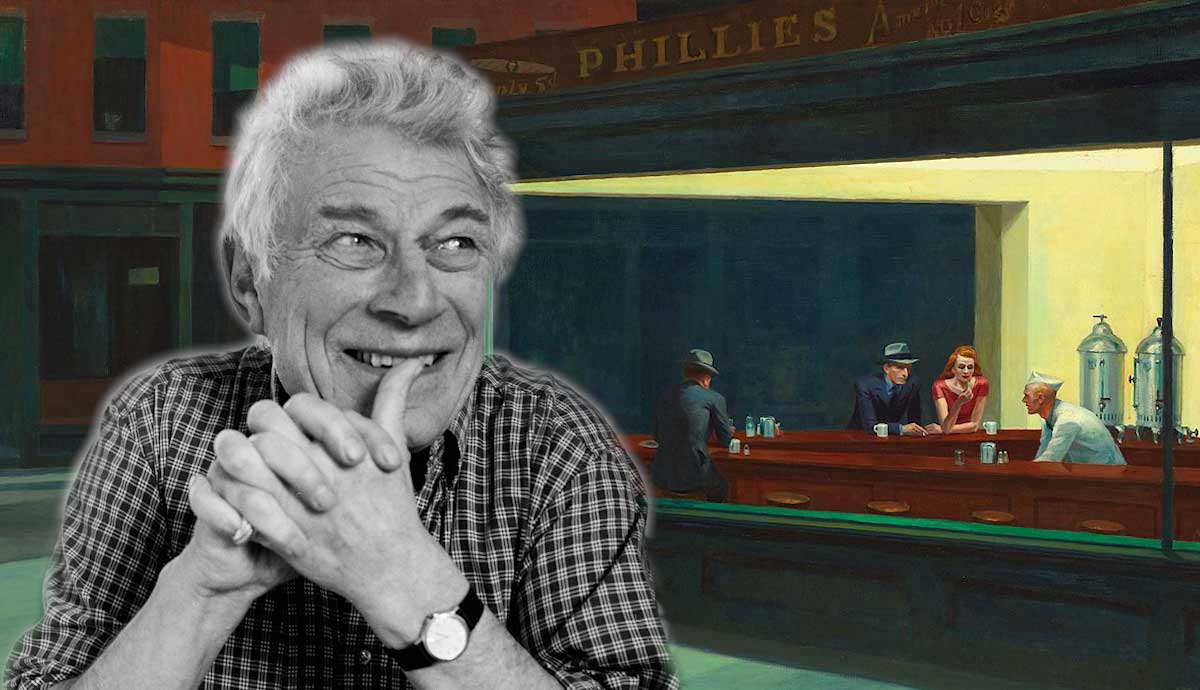

John Berger argues that seeing is not a neutral or passive activity but an active decision. Our relationship to history has been mystified by the ruling classes to justify their role in society and how they got there. This resulted in a disconnected view of history, one which is sterilized, decontextualized and robbed from its “viewing angle”. For Berger, a painting or even a photo reveals a subject who was, at that moment, worth being captured by a person who has a direct relationship to the scene.

Specifically, Berger analyzes mystification in artistic interpretation where works of art are separated from their social context, of the connections between artist/art and are instead explained via elements of their composition, as though the value of a piece of art can be decoded by analyzing style, color, contrast, perspective and so on. This type of ahistorical framework obstructs any alternative explanation. The motto of mystification is that of the ‘Human condition’, that of timeless truths about people which are the subject of the classics.

John Berger on the Reproduction of the Image

With mass media, paintings and pieces of art which until recently could only be seen at their specific place of display, were now multiplied and spread out to the population via cameras and TVs. This reproduction reproduces not only the artwork but it also multiples its meaning and the context in which the meaning is experienced, from one unified meaning in one context, to a fracture of meanings all in different contexts.

The context is the TV, the wallpaper behind it, the viewer’s relative position, the brightness on the TV, the medium, the quality of pixels and so on. Once it’s reproduced, the same artwork is never experienced in the same way.

In a film for example, which might include a shot of a painting, the painting becomes a vehicle to support the filmmaker’s conclusion for the story that is being told. It is no longer a standalone artwork but it is embedded in another context and flow which transforms its original meaning. In a film the images succeed one another and point to something beyond their individual exposition. The film has a dimension of time which doesn’t exist in the painting itself. The film unfolds.

We’re surrounded by reproductions: they form a language, a circuit which envelopes us. The authority of the original painting is displaced, fractured, multiplied. A lot of institutions still cling to it, to the authority of the original. They represent the traditional hierarchies of values and class. The persistence of the static, immovable artworks displayed in large collections and museums aims to emphasize the nobility of the rich over the other classes which can no longer situate themselves in history.

The Equality of Objects

Berger asserts that “Oil paintings did to appearances what capital did to social relations. It reduced everything to the equality of objects”. Everything was permeated and submerged into the inescapable ocean of commodification which gave any activity, any object, a specific exchange value which the owner of the object could get for it in the market.

According to Berger, in no other domain is the gap in quality between different paintings so obvious as it is in paintings, where mediocre works are presented to the observer in equal standing with masterpieces, with no explanation as to what differentiates them. The period of the oil painting corresponds to the rise of the open art market. Many oil paintings were simply completed just for the painter to get the commission he was entitled to, not because he might have genuinely wanted to express something with the painting. Art becomes a job just like any other, composing a sonata or drawing a painting becomes the same act as carrying bricks or controlling the traffic.

The oil painting celebrated a new form of wealth that was emerging in Europe: not only the divine wealth of kings but that of dynamic capitalism. It needed to reflect the power of money, a power which is reflected on the act of the existence of the painting itself. As such, the static materialism of the oil paintings hinders its own capabilities for symbolism. Every symbol which falls in its space of representation is flattened and stripped of its metaphysical character, because the oil painting needs to make everything reachable, material, open to physical contact.

The Meaning of the Classics

When we think about literature, paintings, music composition, sculptures we immediately think of what can be called “The classics”. A classic work is said to be timeless and universally recognised for its high quality. Even people who don’t particularly enjoy a classic can see why the classic is a classic.

“Until very recently – and in certain milieux even today – a certain moral value was ascribed to the study of the classics. This was because the classic texts, whatever their intrinsic worth, supplied the higher strata of the ruling class with a system of references for the forms of their own idealized behavior”

The genre of such classics intends not to teleport the viewer in a new experience but to embellish those which the viewer has already experienced, directing him/her to a way of experiencing in par with the morality of the ruling classes, morality which itself is a glorification of the characteristics of the rich which through their power gain a moral dimension. The behavior of the rich becomes noble and the behavior of the poor is seen as vile or at best humble.

Here the oil painting in particular establishes a relation with property which even affected landscapes. No longer was landscape painting simply done with no commercial background in mind. Natural landscapes were replaced by landscapes of property, of owned land by proud landowners which had the capacity to order such paintings to begin with. Oil paint was perfect for this since it could portray the land with all its substantiality. The landowners would have the chance to enjoy seeing themselves being represented as powerful landowners.

The Integration of Subversion

When we think about someone like Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement, in the collective consciousness we don’t think of them as radical. What they were asking for was surely common sense, reasonable and within the confines of liberalism. The truth is that back at the time these movements faced severe repression by the state and the support wasn’t as widespread as we’d like to believe.

The history of radical subversive movements is revised within liberal societies and made to seem that their acts weren’t revolutionary at all, that they worked within the system itself. In short, they are flattened. This is the contradiction in today’s liberal societies which were shaped by radical disobedience. If the disobedience was successful, it is integrated to give the impression that it worked within the logic of the system. In retrospect people who engaged in revolutionary disobedience are seen as heroes fighting for their rights but yet, today, they tell us that any further disobedience should not be encouraged.

Berger makes the same observation about artists which subvert the rules of their artistic tradition. Whilst while they were alive, they were often neglected and poor, in retrospect we appreciate their genius and originality. Now, they are part of the tradition.

The status quo critic flattens all that is subversive about art and attempts to locate the genius of the artist in color composition, perspective, virtuosity and likewise ahistorical elements of their artwork devoid of any subversive context. Exceptional artists are repurposed and made to fit within the confines of tradition, creating the idea that they weren’t rebelling against the limitations of the traditional artistic role but that they were working within its logic.

John Berger on Ads and Being Insufficient

For Berger, the most common image that confronts us today is the advertisement image. According to him these images do not simply compete with each other in the market for consumers, but at the same time, they deliver a unified message: the message that consumption is integral to happiness and contentment. Advertisements manufacture glamor and insufficiency, the imbalance between one’s current state and one’s potential state which can only meet through the consumption of the product which is being advertised. The publicity image doesn’t simply sell a particular pleasure to be enjoyed through the object. It sells an identity, a reconstruction of social relations and our place within them, it sells a way of being seen by others.

“The publicity image steals her love of herself as she is and offers it back to her for the price of the product.”

This is very unique to our system of production, according to Berger. Never before have we been confronted with such a concentration of images which attempt to signify our insufficiency. Even when we’re not looking at the specific ad or its specific content, the message that we are lacking remains with us unconsciously. We’re so accustomed to being addressed by these images that we no longer grasp their effect on us.

These images belong to the present and yet, they orient us towards a future. This produces a strange effect. Even after we stop viewing the images, one still has the impression that images are still passing us by, like express trains, waiting to be seen. We sit in place, static, and the images are dynamic. Whilst the images compete with one another to be seen by the consumer, they offer him a unified message nonetheless through their common language. It tells them that they need to constantly be up to date with the latest products, with the latest images and that one cannot just sit still.