In his book Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society (2019), Nicholas A. Christakis examines the undeniable similarities between humans and animals. He notes that chimpanzees exhibit distinctive cultures (from grooming practices to the use of tools), crows and crocodiles use tools, elephants develop friendships, and gorillas have language. (2019, p. 275).

Despite such similarities, the reality constructed by human beings appears to be more complex and intricate than any animal accomplishment. Although wolves and lionesses may cooperate in hunting, and bees may share their coordinates when food is located, humans have constructed institutions such as governments, techno parties, and money, which have the power to withstand time, transcend local cooperation and make some individuals more powerful than others. To answer the question of how this is possible, John Searle addresses the topic in two books: The Construction of Social Reality (1996) and Making the Social World (2010).

The Foundation for John Searle’s Philosophy: The Role of Language in Evolution

Before turning to Searle, it is worth saying something about the relationship between language and the history of human evolution.

According to Yuval Noah Harari, the Cognitive Revolution and the emergence of fictive language took place between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago (2015, p. 21). Why is the human language so unique? As mentioned, almost every animal (even insects) has ways of communicating with other members of their species.

For Harari, the key attribute of human language is “the ability to transmit information about things that do not exist at all” (2015, p. 24). Animals can convey information about an imminent threat, such as: ‘Careful! A lion!’ Indeed zoologists have found proof of such types of warnings. But only Homo sapiens could have the ability to say: ‘The lion is the guarding spirit of our tribe,’ using an animal in a symbolic way (Harari, 2015, p. 24).

The Israeli historian underscores that what is revolutionary is not that humans can individually imagine things that do not exist, but that they can do so collectively. Sharing those fictionally created realities allowed humans to cooperate flexibly and beyond small numbers (Harari, 2015, p. 25).

How is it that only humans developed such type of language capability? There are two ways of approaching this question. One is evolutionary and focuses on the physiological and ecological conditions of possibility. In this branch, research is conducted around the gene FOXP2, which mutated in humans and is responsible for new developments in the communications of early Homo sapiens (Ayala, 2010, Chapter 3). Also along these lines, there are neuroscientific endeavors that try to define the differences between human brains and animal brains (e.g. Berwick & Chomsky, 2016).

The second road does not deal with the physiological conditions of possibility but with the logical structure of our language and how that structure reflects unique traits of human cooperation; this is the strategy used by John Searle in his theory of the social construction of reality.

The Ontology of the Social World

Searle distinguishes between features of the world that are intrinsic and observer-relative (1996, p. 9). Intrinsic features allude to the inherent properties of entities. For example, water is a product of the chemical combination of two volumes of hydrogen and one volume of oxygen. Another intrinsic feature is that of mass, which is a property of all matter. Thus, intrinsic features of things are ontologically objective, i.e., they exist independently of any experience of it. Even before humans could theorize about the mass of objects and their chemical compositions, entities already had these characteristics.

On the other hand, some features are observer-relative. Let us imagine a screwdriver. This tool has certain physical characteristics that we can describe (its dimensions and mass). Nevertheless, when we called it a ‘screwdriver,’ what we mean goes beyond its intrinsic features (Searle, 1996, p. 10). That such an object is indeed a screwdriver has to do with the agentive function and status imposed on it, this is, to the way we use it and refer to it.

As mentioned, both humans and animals have the ability to impose functions on things. Chimpanzees are known to use stones to crack nuts and employ sticks to reach termites or ants. Apes eating insects with the help of a tree branch or humans using screwdrivers are illustrations of primitive assignments of function and status.

For Searle, the point of rupture comes when a function (an observer-relative feature) is imposed on phenomena “where the function cannot be achieved solely in virtue of physics and chemistry but requires continued human cooperation” (1996, p. 40). In football, players must remain within the field demarcated by white lines, although there is nothing about these lines that are physically stopping the players from crossing them. All the metrics of a football court are a system of status functions!

Money is another case in point; there is nothing about a piece of paper or plastic (credit cards) that makes them inherently valuable. However, human cooperation and social reality have imposed functions and status on those pieces.

We can now see how the emergence of what Yuval Noah Harari calls fictive language is relevant. The type of functions and status that humans impose do not need to rely on physics and chemistry, but on cooperation, recognition, acceptance, and acknowledgment of that new function.

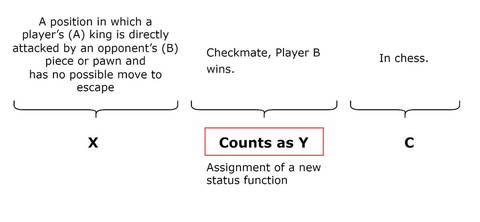

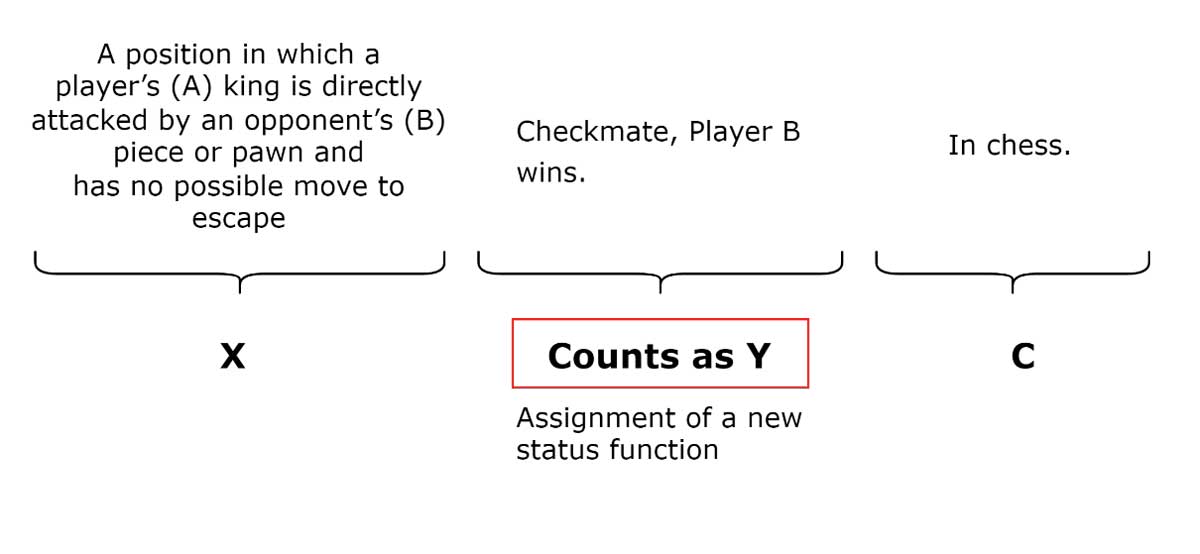

What Searle is identifying is that human beings have the capacity to add another layer to natural reality that is somewhat independent of it: a social reality. We said that contrary to approaches in evolutionary biology and neuroscience, the road taken by Searle is that of logic. In this spirit, he asks himself: what is the logical structure of the status and functions imposition? He will argue that it is this: “X counts as Y in C” (1996, p. 40).

Regulative and Constitutive Rules

To better understand the structure “X counts as Y in C” we first need to revisit a distinction found in Searle’s Speech Act Theory: that of the regulative and constitutive rules. He writes:

“Regulative rules regulate a pre-existing activity, an activity whose existence is logically independent of the rules. Constitutive rules constitute an activity the existence of which is logically dependent of the rules”

(Searle, 1969, p. 34).

Rules forbidding killing fellow humans are regulative because the capacity to kill exists before the rule. On the contrary, the rules of chess, for example, do not regulate any pre-existing activity but create the possibility of playing chess (a new behavior). Chess would not exist outside the set of rules that defines it.

By formulating constitutive rules, humans are creating new realities and behaviors. This relates to the intuition —explored by other philosophers like Wittgenstein or J.L. Austin— that language not only describes reality but changes it or creates new layers of reality. The logical structure of constitutive rules is precisely “X counts as Y in C”. This logical structure in chess could look as follows:

Concisely, when humans impose status functions onto things, they are using constitutive rules. When someone utters “X counts as Y in C” they are assigning to an object ‘X’ a new status-function ‘Y’ in a specific context ‘C.’ One may wonder how it is that such an apparently simple structure is responsible for the complexity of social reality: governments, football games, marriages, nations, churches, traffic lights, and so on.

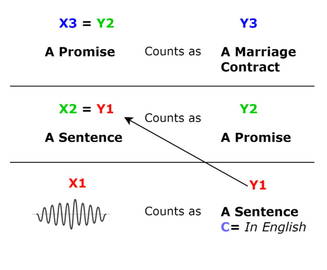

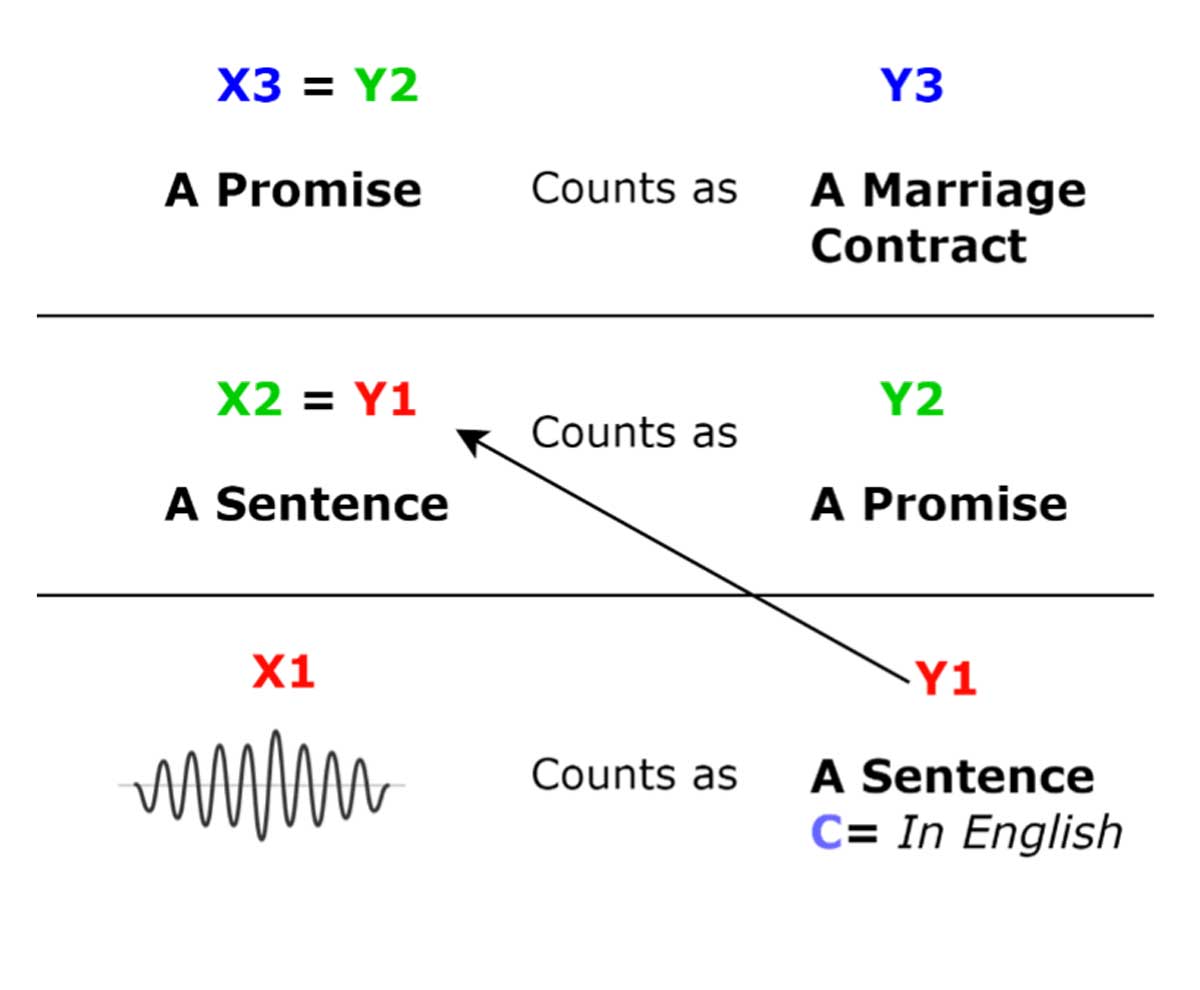

Two formal attributes of constitutive rules answer the issue, namely, they iterate upward and spread out laterally. The complexity of institutional and social reality is partly due to the iteration of constitutive rules such that a ‘Y’ in a lower level is an ‘X’ in a higher one. Searle provides an illustration that goes from vocal noises to marriage (2011). Making certain noises ‘X1’ counts as an utterance of an English sentence ‘Y1’; the utterances of certain sentences in English ‘X2 = Y1 ’ count as making a promise ‘Y2’; promises of some type (X3 = Y2 ) count as being married, all in contexts Cn (Searle, 2011). We can represent this in the following diagram:

Secondly, this logical structure not only iterates in an upward fashion but is also interlocked with others at the same level. In a wedding ceremony, promises are not isolated; there is a wide array of symbols, traditions, and institutions that are operating simultaneously and that depend on the concrete cultural traits of the people in the event. Therefore, our whole social reality is built on innumerable constitutive rules.

Returning to animals that use tools, one could say that there is a primitive “X counts as Y in C” where ‘X’ can be the branch of a tree and ‘Y’ is a tool for getting termites. Nonetheless, the ‘Y’ is always dependent on the physical and chemical composition of ‘X.’ Moreover, there is no iteration: the ‘Y’ in a lower level cannot become an ‘X’ in a higher one, as shown in the diagram. Given that constitutive rules are structures of human language, we can confirm that our language is qualitatively distinct from that of other animals.

Collective Intentionality

Constitutive rules are essentially collective. I cannot take a piece of paper from my notebook and say that it counts as a US dollar; but if everybody would stop recognizing bank notes as valuable, money would simply disappear, leaving aside just its physical and chemical referents.

That constitutive rules are collective does not mean that their validity is a matter of constant consensus: you likely have not received any message from the government asking if you recognize your local national currency. Every time a newborn is introduced to the natural world, she is simultaneously entering a social reality that predates her. Sociologists and philosophers of the social sciences named this “social structure”. We can understand the social structure as the network (complexity) of constitutive rules (Searle, 2010, p. 31). This reality is created, but it exercises an immense influence over every individual, like the need to use one currency over another.

What Can John Searle’s Theory Tell Us about Hierarchies and Power?

Dominance hierarchies have been discovered in birds, wolves, and baboons. For instance, wolves live in families in which the parents dominate the pack. Their dominance depends on their family status; they are not a matter of cooperation.

With constitutive rules, the story is different. Social reality gives power to people based on their social position and the function and status attached to it. The President of the United States has the power to veto bills, but this power is not derived from his inherent nature; it belongs to the social position he is granted. The day when Joe Biden, ‘X’, no longer counts as ‘Y’ (The President of the United States), he will no longer have the power to veto any bills. As Searle put it: “the function cannot be achieved solely in virtue of physics and chemistry but requires continued human cooperation” (p. 40). In contrast to wolves, social power resides in artificial status positions created by speech acts and mutual recognition.

To summarize, John Searle’s theory can elucidate the differences between humans and animals when it comes to the construction of social reality. By using certain speech acts, which have the logical structure of “X counts as Y in C”, humans add new functions and new statuses to phenomena that go beyond their physical and chemical compositions and that require human cooperation. From this logical structure, the entire complexity of society can be derived.

Literature

Ayala, F. J. (2010). Am I a monkey? Six big questions about evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Berwick, R. C., & Chomsky, N. (2016). Why only us: Language and evolution. MIT Press.

Christakis, N. A. (2019). Blueprint: The evolutionary origins of a good society (First edition). Little, Brown Spark.

Harari, Y. N. (2015). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind (First U.S. edition). Harper.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech Acts. An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. (1996). The construction of Social Reality. Penguin Publishing Group.

Searle, J. (2010). Making the Social World. Oxford University Press.

Searle, J. (2011). Lecture: Language & Social Ontology. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaQ7Q5I4kj4