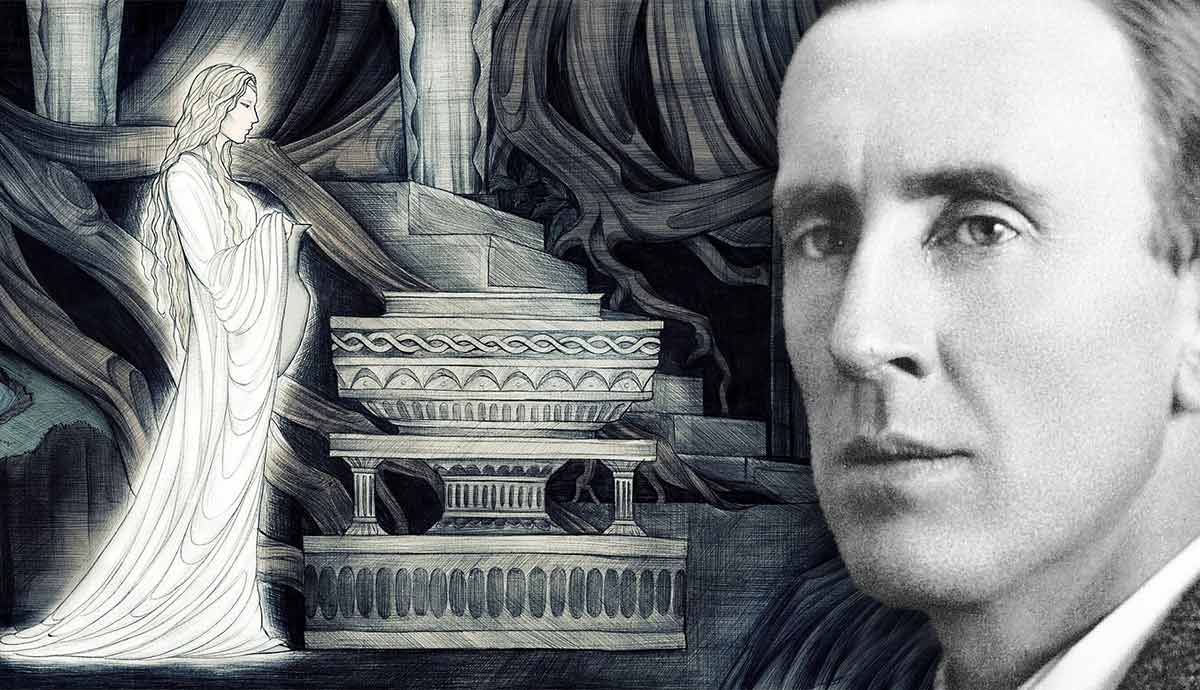

J.R.R. Tolkien was a scholar of Anglo-Saxon language and literature. Germanic hero legends and Nose sagas played a significant part in the construction of his Middle Earth legendarium. However, at its heart are specifically Christian ideas and themes. His One God created a universe from nothing. Angels and men experience temptation and lust for power. Some fall. Others fight as prophets, priests, or kings. Some undergo a death and resurrection or return for a final, apocalyptic battle. Eucharistic and Mary-like Catholic elements are also present.

A Monotheistic Worldview

In Tolkien’s legendarium, there are many celestial beings, including the angelic Maiar and the godlike Valar. In fact, several of the Valar are direct equivalents of gods from Greco-Roman mythology. Ulmo, Lord of Waters, is Middle Earth’s version of Neptune, while Aulë is the craftsman and smith of the gods, like Vulcan. But, unlike in polytheistic religions, in Tolkien, there is one God who rules over all — Eru Ilúvatar, the One, He That is Alone.

It is accurate to call this cosmology a version of monotheism. This is the belief that there is one God rather than many gods. However, there are different kinds of monotheism. The philosopher Keith Yandell proposed that there are three kinds of generic philosophical monotheisms. They differ from each other in terms of how God relates to the world by acting in human history (a doctrine called divine providence).

- Greek monotheism — The one God has always existed but so has the world. There is no creation and or providence. However, the world is mutable and imperfect, unlike God.

- Hindu monotheism — This is the belief that the world has always existed because God wants it to. God only acts in the world via private revelations and events (“weak providence”) or is not providentially active at all (as in Deism).

- Semitic monotheism — This is the belief that the world was freely created by a God either in time or with time. God acts in the world both in public historical events and in private revelations (“strong providence”). This is the monotheism of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Tolkien’s is of this sort.

However, there are differences between Tolkien’s cosmology and that of his Christianity. In the Book of Genesis, God created all things alone, speaking them into existence with words of power. In Tolkien, the creation account is called the Ainulindalë or the Music of the Ainur. Eru Ilúvatar allowed his gods to participate in crafting the musical themes that became the places and people of the world. He also allowed them to take part in the physical actualization of the themes as the world was formed over time.

Of Power and Temptation

There have been many attempts to find a main theme from The Lord of the Rings, with suggestions ranging from the traditional (sacrifice or hope) to the modern (environmentalism versus technology). The name and title of the work strongly suggest that the Ring itself is a symbol that serves as the story’s main theme, as well as the device that drives the entire plot forward to its conclusion. This Great Ring is a ring of power, as are all the other rings listed in the rhyme, “Three Rings for elven kings under the sky…”

Power is what the characters in the story crave and the temptations of power are what they experience. The form that this temptation takes differs according to the order of rank and the “will to power” of the character. Both dark lords Morgoth and Sauron lusted for dominion over others, although for different reasons. Morgoth wanted the power to destroy, and Sauron wanted the power to order. But power isn’t just for the villains. Lady Galadriel came to Middle-Earth and founded Lothlórien to rule a realm there at her own will.

Along with the temptations of power came the power of temptation. Many characters in the story were tested by the Ring. Some, in a Christ-like way, resisted temptation (Gandalf, Galadriel, Aragorn, Faramir, and Sam). Others, following Adam and Eve, failed (Sméagol, Saruman, Boromir, and even Frodo at the end). The only one immune from the temptation of the Ring was the mysterious Tom Bombadil. The Ring had no power over him because he had no interest in power. If there is a political message to The Lord of the Rings, it is the danger of wielding power over others, even for good.

“My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning the abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs) …The most improper job of any man, even saints (who at any rate were at least unwilling to take it on), is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity…”

JRR Tolkien, letter to his son, 1943 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien).

Fallen Angels and Men

The Fall of Man is the tragic story of the human transition from a state of original innocence to one of sin, guilt, and death. It is not just the story of two individuals—Adam and Eve in their expulsion from paradise—but has wider implications for the entire race, and represents the fall of each of us. Some biblical scholars, like Michael S. Heiser, argue that there are other biblical falls too: the fall of Satan that brought about the temptation of Eve in Eden; the fall of the Sons of God when they married the daughters of men in Genesis 6; and the fall of nations at the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11.

Tolkien portrays the fall of a number of individuals from one of original goodness and honor to one of corruption and evil. The most obvious is Melkior, who became Morgoth. This is the greatest and most significant fall. It is reflected in the lesser fall of Sauron, and even in the fall of Saruman. But Tolkien uses the fall motif to include events as well as individuals. The fall of Melkor begins in the Ainulindalë, the music of creation, into which Melkior, out of hubris, struck a loud, vain, and disruptive note. Other falls include:

- The Kinslaying at Alqualondë, in which elves led by Fëanor stole from and murdered other elves

- The destruction of Númenor, the greatest civilization of men

The Three Heroic Offices

An interesting question to ask is: Who is the hero in The Lord of the Rings? A solid case can be made that three of the characters fulfill this role.

1. Frodo, the ringbearer who inherited the problem and who saw it through to its ultimate solution. The story started and ended with him more than any other.

2. Gandalf, the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring, was called the Enemy of Sauron. He was the first to identify the Ring and was chief in all the plans to destroy it.

3. Aragorn, the prophesied king who returned, the heir of Isildur (who first cut the Ring from Sauron’s hand), the uniter and healer of the lands, and captain of the Host of the West.

Each of these three characters has roles that reflect the three offices of Jesus Christ, the anointed and appointed deliverer of Humanity. As a priest, he bears our burdens of sin and punishment, taking the weight of the world on himself, offering up himself to rescue us. As a prophet, he reveals the hidden mysteries of the way of salvation and encourages us with messages of hope. And as king, he defeats all our enemies, establishes his kingdom of peace, and returns to bring all plans to completion.

These are broad strokes but they apply to many of the plot particulars. For example, Frodo carries wounds from his time as ring-bearer that never fully healed, just as Jesus retains his sacrificial scars even after his resurrection. Or, as Aragorn takes the Paths of the Dead into a subterranean complex under the White Mountains, Jesus descended into the underworld between his death and resurrection — an event known as the Descent into Limbo or the Harrowing of Hell.

Death and Resurrection

The most obvious instance of resurrection in Tolkien’s works is that of Gandalf after his fight with the Balrog in Moria, a being who was a Maiar like him, only fallen into evil. Although Gandalf the Grey defeated his enemy, it cost him his life. Gandalf’s body lay at the peak of Zirakzigil, while his spirit traveled beyond space and time. Because his mission was not yet fulfilled, he was sent back to Middle Earth as the enhanced Gandalf the White, reborn greater in dignity and power than before.

There are other resurrections in Tolkien, both of the bodily and figurative kind. Frodo was resurrected from near death when he was struck by the Morgul knife but healed by Elrond. Aragorn was resurrected when he reappeared from the Paths of the Dead and returned to Gondor after a long absence. The White Tree of Gondor was dry and lifeless during the rule of the Stewards before Aragorn revived it. There is also an elf-lord called Glorfindel who died killing a Balrog at the Fall of Gondolin in the First Age but is also present at the Council of Elrond in the Third Age.

Of Returns and Final Battles

The Dagor Dagorath or Battle of all Battles is the last, apocalyptic war in Middle Earth before its end. It shares much in common with the biblical concept of Armageddon — an end times final conflict between good and evil, after which creation will be renewed. Melkor, the fallen Valor who became Moroth, will return to lead all the forces of darkness. Against him will stand the host of Valinor. Among these will be Túrin Turambar, son of Húrin, returning to avenge all fallen men. It is Túrin who will finally kill Melkor with his black sword Gurthang (Iron of Death). Then the world will be remade, and the dead arise.

All this was prophesied by Mandos, Judge of the Dead and Master of Doom. But as well as this apocalyptic return, there are other prophesied returns in Tolkien. Boromir dreamt that the “sword that was broken” would return to play a part in the breaking of “Morgul spells.” And so Narsil, the broken sword of Elendil, was reforged into Andúril — Flame of the West. Aragorn also quoted a prophecy by Malbeth the Seer about Isildur’s heir passing the Door to the Paths of the Dead. Aragorn himself is the king who returns in the final volume of the story.

Tolkien as a Catholic

The doctrines and religious ideas mentioned so far are common to Christians of all denominations. But Tolkien himself was a devout Catholic, not a proponent of Mere Christianity like CS Lewis. One of the most obvious Catholic allusions in The Lord of the Rings is to the Eucharist or Mass. Before the Fellowship leaves Lothlórien, Galadriel has them drink from a common cup and then provides them with lembas. This is described as elvish waybread, which has enough supernatural power to keep them nourished for many days. These are the two elements of the sacrament of Holy Communion.

An even more obvious Catholic aspect is the portrayal of Galadriel herself as a Mary figure, a queen and great lady, a miracle worker, and a bestower of gifts. However, a more fitting candidate is the Valar queen Varda, who the elves call Elbereth (star-queen) and Gilthoniel (star-kindler). Although she is never seen in the story, her name is invoked for a blessing (“May Elbereth protect you!”) or as a battle cry against evil (“O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!”) or as a sacred oath (“By Elbereth and Luthien the Fair”). They also sing to her in what Frodo called songs of the Blessed Realm.

“Snow-white! Snow-white! O Lady clear!

O Queen beyond the Western Seas!

O Light to us that wander here

Amid the world of woven trees!Gilthoniel! O Elbereth!

Clear are thy eyes and bright thy breath!

Snow-white! Snow-white! We sing to thee

In a far land beyond the Sea.”