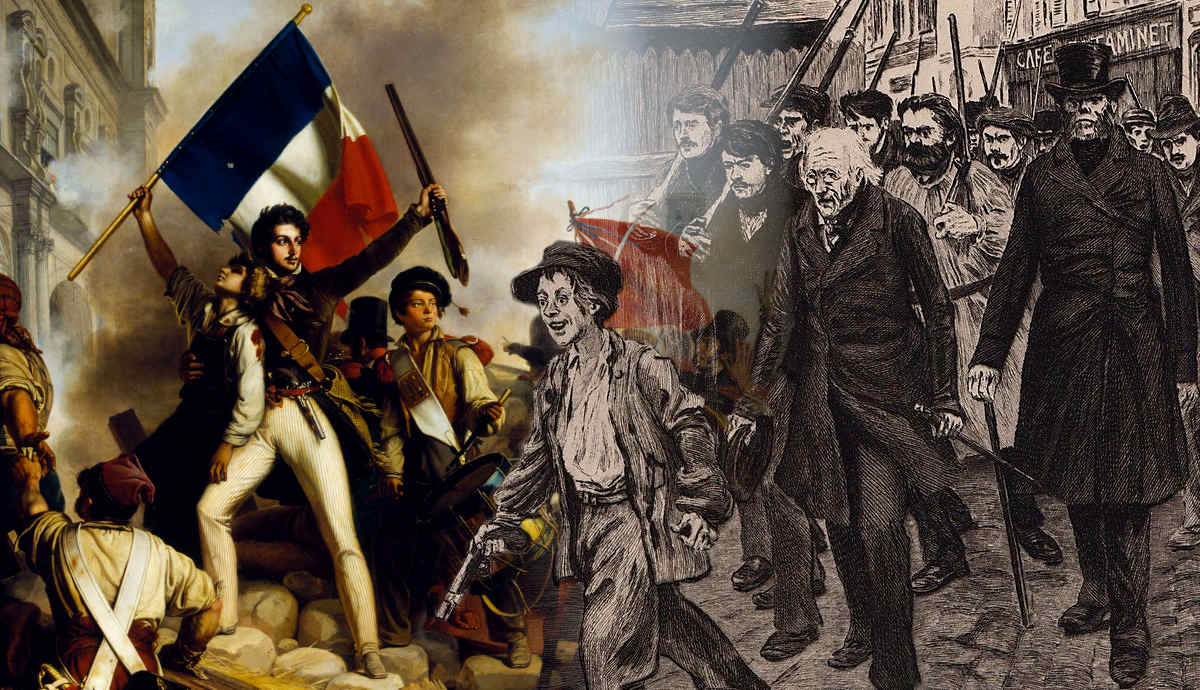

The June Rebellion occurred on June 5–6, 1832, in Paris, France. It was an attempt by the republicans of Paris to resist the newly-established monarchy of Louis Philippe, who tried to institute hardline reforms, including ending public works programs to provide for the unemployed. The rebellion erupted unexpectedly after the death of Jean Maximilien Lamarque, a famous army commander, parliamentarian, and monarchy critic, who fell victim to the deadly cholera epidemic. On June 5, 1832, anti-monarchist republicans seized Paris and built barricades. Although consisting of more than 100,000 participants, the rebellion failed and was soon over as it lacked wider public support. The June Rebellion inspired French novelist Victor Hugo to write one of his most famous novels, Les Misérables, published in 1862.

June Rebellion: Inspiration for Hugo’s Les Misérables

Victor Hugo, a well-known author of the 19th century, was inspired by the events of 1832 to write one of his best-known works, Les Misérables. However, it is a common misconception that Les Misérables takes place during the first French Revolution of 1789. This misunderstanding is brought on by musicals and movies that emphasize the revolutionary aspect of the work more, and people largely associate it with France’s best-known historical event of the modern era, the first French Revolution. However, Victor Hugo described the events of the June Rebellion in Les Misérables, which happened 43 years after the storming of Bastille.

During the June Rebellion, when the gunfire started, Victor Hugo was nearby in the Tuileries Gardens, working on a play. He decided to follow the sounds. Unaware of the barricades that were erected everywhere in Les Halles, he found himself in the center of the heated fighting. When he started working on Les Misérables in 1845, he decided to incorporate the events of the June Rebellion he witnessed as a young man. So what was the June Rebellion exactly, and why did it happen?

France Before the June Rebellion

France encountered the Second French Revolution, also called the July Days, in 1830. The first French Revolution occurred in 1789, resulting in the ascension of Napoleon Bonaparte and radically transforming the French political environment by abolishing the monarchy and the feudal system. The July Days established a constitutional monarchy, overthrew the Bourbon monarch, King Charles X, and replaced him with his more liberal cousin Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, whose reign was also known as the July Monarchy. The principle of hereditary rights was replaced by popular sovereignty.

During this period, France became divided between different political groups with their own goals and visions of France. The supporters of the overthrown Bourbon Dynasty were called Legitimists, who aspired to grant power to the man they regarded as the true King of France: Charles’s grandson and designated successor, Henri, Count of Chambord. On the other hand, supporters of the new July monarchy were referred to as Orléanists, while at the same time, the Bonapartists, who sought the return of Napoleon Bonaparte’s descendants, were still influential.

After Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat, the Congress of Vienna, held in 1815, returned France to its 1791 borders. Being in a state of disarray, France was an outsider among other influential European powers (the Austrian Empire, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, and Prussia), which were just about to establish a new world order.

Besides international isolation, France struggled internally. Charles X became king in 1824 after the death of Louis XVIII. King Charles’s policies were rather reactionary, and he soon lost popular support. Particularly decisive were his decisions to pass legislation that paid an indemnity to nobles whose estates had been confiscated during the Revolution. This proved to be a costly initiative and upset the middle-class French population, who were already suffering economically.

Additionally, the Anti-Sacrilege Act was passed, which included the death penalty provision. These policies culminated when, on July 15, 1830, King Charles issued ordinances suspending the liberty of the press, excluding the commercial middle class from future elections, and calling for new elections. Coupled with significant economic problems caused by harvest failures and food shortages, a revolt against the king seemed inevitable.

As a result, on July 26, 1830, opposition forces erected barricades in Paris. The revolt lasted five days, and eventually, King Charles was forced to abdicate and flee from Paris to Great Britain. His defeat was celebrated as a victory over absolute rule. Louis Philippe, the cousin of Charles X, took the throne and established a constitutional monarchy, securing political and social ascendancy for the French middle class, or upper bourgeoisie, over the aristocracy.

A new monarchy could not cope with France’s economic problems, and the cost of living dramatically increased, which created broader dissatisfaction in the French population, especially in rural territories. The cholera outbreak worsened the economic and social situation of Parisians. Lower-income areas suffered higher losses to the disease because they were more likely to have contaminated water supplies. Soon, the cholera epidemic worsened the living conditions and claimed the lives of nearly 19,000. Some even stipulated that the government intentionally poisoned wells to subdue the masses, further exacerbating class tensions.

The opposition steadily grew across France. Particularly active were silk workers in Lyon, who organized a rebellion in December 1831 to protest the trembling economy and subsequent drop in silk prices, which caused a reduction of workers’ wages. The National Guard suppressed the rebellion. This was followed by a second insurgency in Vendée, organized by Caroline Duchess of Berry, Henri’s mother and perceived legitimate heir to the throne. The government also suppressed this attempt, and the Duchess was imprisoned until 1833. Then in Paris, another revolt happened in February 1832. Legitimists, also known as Carlists, who supported the Bourbon dynasty, had unsuccessfully attempted to capture members of the royal family. The failure of this rebellion cemented the fall of the Bourbons and was the last violent effort by the dynasty to reclaim the throne.

The opposition finally culminated after the death of the hero of the Napoleonic Wars, Jean Maximilien Lamarque, on June 1, as a result of the cholera pandemic. He was given a public funeral, which suddenly transformed into a spontaneous protest. Republicans saw this turn of events as an opportunity to join the mass gathering and give stimulus to a more powerful resistance against the monarchy.

The June Rebellion

General Jean-Maximilien Lamarque’s funeral was held on June 5, 1832. As reported, thousands of Parisians attended the process, which was not a surprise as, throughout history, funerals were regarded as an event for mass mobilization in French political culture. The public funeral quickly turned into an urban insurgency led by the republican opposition, with approximately 100,000 Parisians joining. They believed that the monarchy of Louis-Philippe had betrayed them and deepened the class struggle by defending the interests of the bourgeois elite. Taking control of the cortege, protesters redirected the funeral to the historic Place de la Bastille, the site where the French Revolution started in 1789.

Many European political refugees, mainly Poles, Portuguese, Germans, and Italians living in France, played an active role in the demonstrations, as Lamarque was well-known for his objections to the French government’s foreign policies, particularly its reluctance to support the liberation of other European people following the 1830 revolutions. When the July monarchy was established, liberals throughout Europe hoped France would join the wave of a general social revolution.

The gathering at the funeral procession became disorganized when a red flag with the slogan “Liberty or Death” was raised, and shots were fired toward government troops. Around rue Saint-Martin and rue Saint-Denis, the opposition erected barricades. Twenty-thousand soldiers of the Paris National Guard were joined by around 40,000 regular army soldiers under the authority of King Louis Philippe on the night of June 5–6. Victor Hugo and other contemporaries perceived the resistance and barricades of June as natural extensions of the cholera epidemic, or the “political continuation of a biological crisis.”

The Cloître Saint-Merri was the scene of the decisive battle, which lasted until the early hours of June 6. In total, the rebellion claimed the lives of 800 people. On the side of the insurgents, there were 93 killed and 291 wounded, while the army and national guard suffered losses of 73 soldiers and 344 wounded. At this point, King Louis Philippe decided to appear publicly to demonstrate that he was still in charge of the capital and that the insurrection had failed to spread further.

The rioters were put on trial and punished, and the king managed to consolidate his power. Louis Philippe and his ministers imposed stricter controls over the press, making convictions for “political agitation” easier to obtain in courts.

Ultimately, the June Rebellion did not achieve its aims, nor was it able to threaten the ruling regime, and it failed to acquire broader popular support for the victory. Its failure also disappointed those who sought to reestablish a Bonapartist regime and those who sought to resurrect a new French Republic. However, the June Rebellion served as a prerequisite and catalyst for French society to resist, which eventually led to the major revolution overthrowing the monarchy of Louis Philippe in 1848.