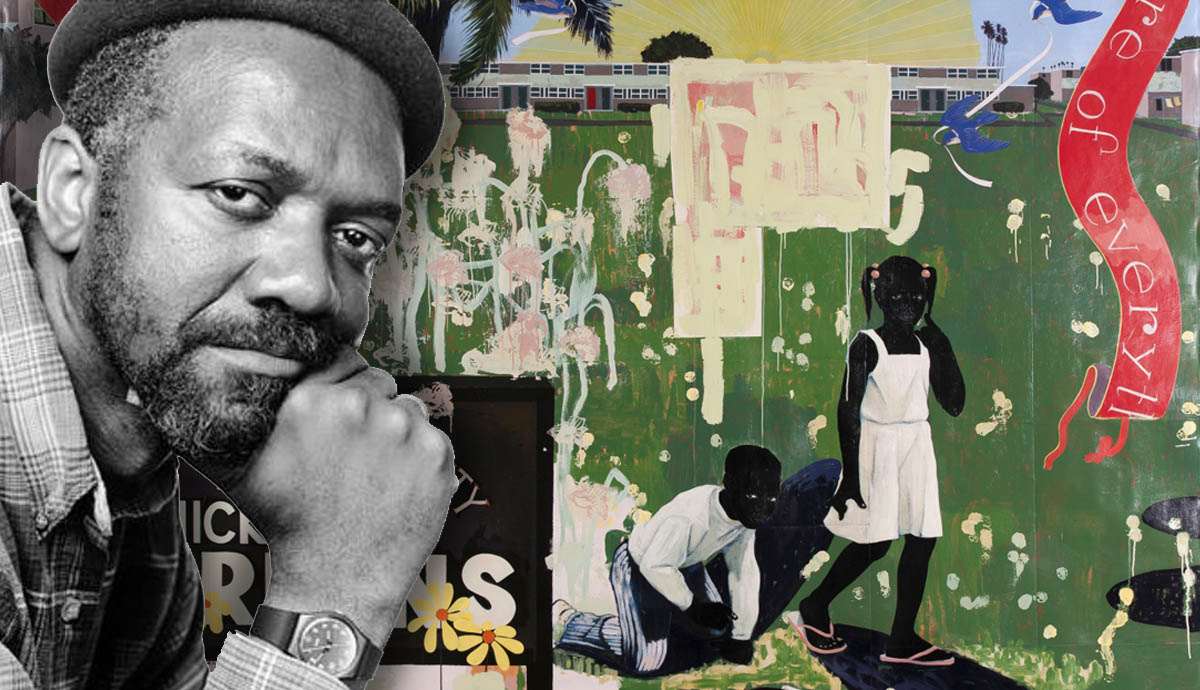

Encounter a Kerry James Marshall painting and you will encounter Black bodies. There are Black bodies dancing, Black bodies relaxing, Black bodies kissing, and Black bodies laughing. The matte, ultra-dark skin Marshall gives the people in his paintings is not only a signature stylist move but an affirmation of Blackness itself. As Marshall puts it, “When you say Black people, Black culture, Black history, you have to show that, you have to demonstrate that black is richer than it appears to be.” It’s a choice meant to be didactic, Marshall says, meant to instruct that “[Blackness] is not just darkness but a color.”

Who is Kerry James Marshall?

Kerry James Marshall might be the most prominent Black artist you’ve never heard of. For over three decades his figurative paintings, sculptures, and photographs have been shown in galleries across Europe and North America. Although, even within the world of Black art Kerry James Marshall was a frequent outsider. While he had won numerous fellowships and awards, including a MacArthur Genius Grant in 1997, it wasn’t until his first major retrospective in 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago that Kerry James Marshall’s virtuosic scope was fully recognized. That exhibition finally credited him as a great American artist of portraiture, landscape, and still-life.

Kerry James Marshall was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised primarily in Los Angeles, California. His father was a postal worker with a talent for tinkering, mostly with broken watches that he would buy, fix, and sell. Their home in the Watts neighborhood of L.A. positioned Marshall close to the emerging Black Power and Civil Rights movements of the 1960s. This proximity would have a substantial influence on Marshall and his work. He eventually earned a B.F.A. from Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. It was there he continued a mentorship with the social realist painter Charles White that had started in high school.

Finding the Lost Boys in Contemporary Art

In 1993, Marshall was thirty-eight and living in Chicago with his wife, the actress Cheryl Lynn Bruce. He had recently moved into his first big studio space when he made two paintings that were different from anything he’d done before. The new paintings were nine feet high by ten feet wide—much larger than anything he’d done in the past. They featured figures with ultra-black skin. These paintings would change the trajectory of Kerry James Marshall’s career forever.

The first, “The Lost Boys,” was a depiction of a crime scene involving the police and two young, Black boys. The children stare out at the viewer in an unsettling way while surrounded by police tape. Marshall has said the visuals on the canvas come from his years growing up in South Central Los Angeles in the 1960s. A period when street gangs began to rise to power, and the violence increased, markedly.

Marshall told The New Yorker, that when he finished the painting, he was very proud. He stood looking at them, feeling they were the type of paintings he’d always wanted to make. He said, “It seemed to me to have the scale of the great history paintings, mixed with the rich surface effects you get from modernist painting. I felt it was a synthesis of everything I’d seen, everything I’d read, everything that I thought was important about the whole practice of painting and making pictures.”

Black Style as Black Art

One of Kerry James Marshall’s most famous works is called “De Style.” The painting’s title is a riff on the Dutch Art Movement of De Stijl, Dutch for “style.” The De Stijl was a movement that ushered pure abstraction into art and architecture. The setting in Marshall’s painting is a barbershop, identified by a window sign that reads “Percy’s House of Style.” The viewer’s focus is taken to the men’s extravagant hairstyles, large and ornate. The scene gestures toward the importance of hair within Black culture, as well as the significance of style. Marshall has pointed out the prominence of style while growing up as a Black teenager in Los Angeles. “Just walking is not a simple thing,” Marshall told the curator Terrie Sultan. “You’ve got to walk with style.”

“De Style” was Marshall’s first major museum sale. The Los Angeles County Museum purchased the painting the same year it was made for “around twelve thousand dollars.” The sale cemented Marshall’s career ambition of painting large-scale Black bodies and Black faces into gallery and museum spaces where they were absent. Marshall had been troubled by that absence since childhood, and with the painting of these first two pictures, he recognized his path forward in the art world.

Marshall’s Garden Project: Painting the Hope in Public Housing

In the following years, Marshall turned his lens on the U.S. public housing projects. An originally well-intentioned government plan to assist low-income families, the housing projects only intensified poverty and eventually housed a drug crisis. Today, most voices within the Black community see the projects as complicated terrain, both materially and conceptually. While they are a place of significant pain, they are also a space where children grew up and families made happiness. Marshall leaned into this complexity with a group of paintings titled the “Garden Project.”

In the “Garden Project” series, instead of the drug and gun violence many housing projects are known for today, Kerry James Marshall’s paintings present smartly dressed Black folks enjoying themselves. The tapestry-like canvases depict children playing and attending school amidst deep blue skies, lush green lawns, and cartoonish songbirds. The results are paintings overflowing with an almost Disneyesque type of happiness.

In an essay from 2000, Marshall says that he wanted to evoke some of the hope that was originally present when the housing projects first began. Presently, we might remember the poverty and despair in the projects, but Marshall intended to show the utopian dreaming before the disaster. But he also wanted to tinge that dreaming with a hint the despair. The Disney-like elements play to the fantasy of it all. It’s also clear that here, as in most of Marshall’s work, we see a Black artist not interested in painting Black trauma. Instead, Marshall offers a Black American experience not solely about oppression. A story about Black life in various spaces of joy.

The Birth of the Ultra-Black Body

It’s in the “Garden Series” that Kerry James Marshall began to evolve the dense, ultra-dark black bodies that would become one of his most vital contributions to Black art and the broader contemporary art world. A 2021 New Yorker profile, tracks how Marshall started by working with three black pigments that can be bought in any paint store: ivory black, carbon black, and Mars black. He took these three signature black colors and started to mix them with cobalt blue, chrome-oxide green, or dioxazine violet. The effect, which is only completely visible in the original paintings, not in the reproductions, is something entirely his own. Marshall claims that it’s this mixing technique that got him to the place he is now, where “the black is fully chromatic.”

Expanding the Western Canon

There is a consistent effort in the work of Kerry James Marshall to speak in the languages of painting giants who’ve come before him. The “Garden Series” is one example, as it takes up the pastoral language of the Renaissance; Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass” or that painting’s origin point, Titian’s “Pastoral Concert.” Marshall’s allusions are largely medleys or mixtures of various styles and eras. A Renaissance mashed-up with contemporary magazine images. Among all this, there is one prodigious constant, the Black body.

If Western Art presents itself as a canon of the beautiful and noteworthy, what does it say that the Black body is largely absent from that catalog? Of course, there are figures visible from time to time throughout history, but until recently there has been no significant chronicle of black figures in the Western painting tradition. In 2016, Kerry James Marshall told the New York Times, that “When you talk about the absence of black-figure representation in the history of art, you can talk about it as an exclusion, in which case there’s a kind of indictment of history for failing to be responsible for something it should have been. I don’t have that kind of mission. I don’t have that indictment. My interest in being a part of it is being an expansion of it, not a critique of it.”

Kerry James Marshall – Painting the Contrast

Color has always played a central role in the art of Kerry James Marshall. In 2009, Marshall began a series of paintings that took his career-long exploration of color to a new place. He made a sequence of oversized paintings of posing artists. In the principal painting of that series, “Untitled (painter)” (2009), Marshall shows a Black woman artist, her hair in an elegant up-do, holding a tray filled with primary colors. Most of the blobs on her color palette are pinky, fleshy colors, and there is a total absence of black. Everything on the palette appears to exist in contrast to her dark, black skin. Behind her is a mostly unfinished paint by numbers piece, perhaps a gesture to expressionist tradition. In the pose, her brush sits poised over a splotch of white paint.

This is a subtle and distinct method of Kerry James Marshall. An artist whose work often requires the viewer to pour over the painting decoding the history, allegory, and symbolism. Or, just as often, compels the observer to take it all in and marvel at all that’s been missing for so long.