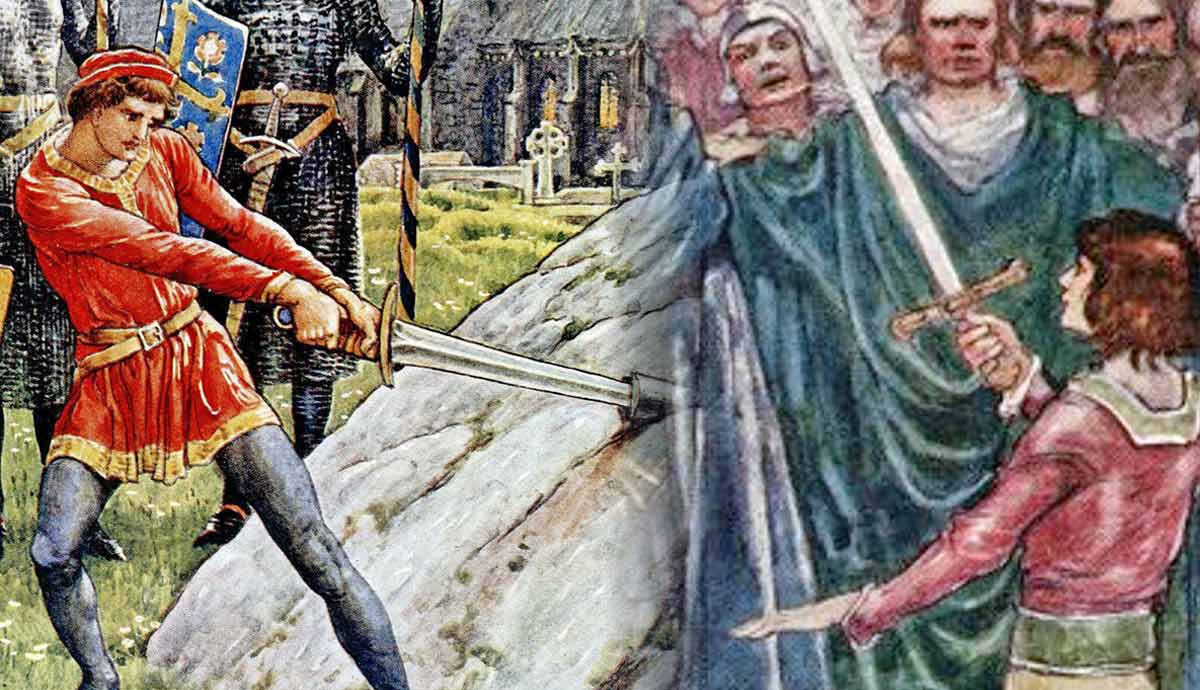

According to legend, King Arthur was a war leader who fought in Britain against the Anglo-Saxons in the 6th century CE. The medieval manuscript Historia Brittonum describes Arthur as fighting against the Anglo-Saxons in twelve battles at nine different locations. There has long been considerable debate over the exact locations mentioned in this text. With the benefit of modern scholarship and archeology, can we determine where these battles took place?

Arthur’s Anglo-Saxon Battles

It would be remiss to ignore the fact that Arthur’s historicity is by no means universally accepted. Many scholars believe that he was either a fictitious character or a figure of folklore and myth who came to be historicized over the centuries. Nonetheless, many other scholars accept that there was likely a historical figure behind the legend. In any case, the question of where Arthur’s legendary battles occurred is not dependent on Arthur being real. Numerous scholars who reject Arthur’s historicity nonetheless attempt to identify the locations on the Historia Brittonum’s battle list.

With this foundation established, what do we know about Arthur’s battles? According to the Historia Brittonum, they occurred at some point after Octa became king of Kent but before Ida became king of Bernicia. That would place them somewhere in the first half of the sixth century. These battles are presented as being highly significant and damaging to the Saxons.

The Most Certain Location: The River Dubglas near Lincoln

The nine battle sites listed in the Historia Brittonum are: the River Glein, the River Dubglas, the River Bassas, the Celidon Wood, the Guinnion Fort, the City of the Legion, Tribruit, Breguoin, and Badon. There is controversy and debate surrounding every single one of them. However, one particular location has general agreement among scholars. It is actually a secondary location rather than one of those nine.

The River Dubglas is described as being in “the region of Linnuis.” Linguists understand that the place name element “uis” is derived from the Latin enses. Therefore, Linnuis must be another form of the place name “Lindenses.” This could also be written as “Lindensia.” This is precisely the term that was historically used for the region of Lincoln.

There are a handful of scholars who still try to argue that Linnuis might be identifiable as another similarly-named region. Nonetheless, on the basis of the aforementioned evidence, the vast majority of scholars accept that Arthur’s second battle site in the Historia Brittonum is set somewhere near Lincoln.

The River Glein

The first of Arthur’s battles can also probably be placed in Lincolnshire. The name of the first battle site is the River Glein, and most scholars agree that this can be identified as one of the two River Glens in Britain today. One of these is in Northumberland, while the other is in Lincolnshire. On the basis of the second battle site explicitly being placed in Linnuis, identifiable as the region surrounding Lincoln, the second of these is the obvious choice.

Supporting evidence for placing the Battle of the River Glein in Lincolnshire comes from an obscure but fascinating tradition preserved in a 12th century document. This document, entitled Hanes Gruffydd ap Cynan, mentions Arthur only briefly. However, it specifically says that Arthur, during his first battle, had to flee due to treachery at the city of Caer Lwytcoed. This place name derives directly from the Roman name for Letocetum, in Staffordshire. However, it was commonly used by medieval writers to denote Lincoln.

Battling in the Midlands

As we said previously, identifying the locations of Arthur’s nine battle sites does not depend on the assumption that Arthur actually existed. Nonetheless, if we do entertain the possibility that he was real, as many scholars do, what bearing would this have on the subject?

The idea that Arthur fought against the Anglo-Saxons in the Midlands, around Lincolnshire in particular, is very plausible. Lincoln appears to have been one of the most important Anglo-Saxon centres in this period. Thus, it would have been a prime target for a Brythonic war leader and make sense as the setting for Arthur’s battles. Brythonic refers to a group of Celtic languages that includes Cornish, Welsh, and Breton.

This is in contrast to most other suggestions, which are locations right on the fringes of Anglo-Saxon territory. Of course, such fringes would logically have been the site of conflict as groups fought to expand their territories. But this would diminish the importance of the battles as it would not represent the Anglo-Saxons encroaching on central Briton territories.

While there is nothing in the Historia Brittonum itself that would be incompatible with the scenario of fringe battles, there is other evidence that makes it unlikely. Modern archeological research has revealed evidence of a reverse migration of Anglo-Saxons from Britain in the first half of the 6th century.

This is also supported by two medieval literary sources. One of these is a 9th century record which provides some information concerning Theuderic, king of the Franks. According to this, Theuderic allowed Anglo-Saxons leaving Britain to settle in his territory. This account is set in the 530s, exactly when Arthur was supposedly fighting his battles according to the Historia Brittonum.

Based on this, a good argument could be made that Arthur was not merely fighting them on the fringes of their territory, preventing them from acquiring more. Rather, he was driving the Brythonic army fully into their land, fighting against them at key locations and causing many of them to retreat.

The River Bassas

A far more controversial location is the River Bassas. This has proven notoriously difficult to pin down because the name is simply so unusual. A common suggestion is Baschurch in Shropshire, recorded in Welsh texts as the Church of Bassa. However, the obvious problem with this is that Bassa is the name of the church, not the nearby river.

In fact, it appears that there is only one location in Britain with a name which truly matches the Historia Brittonum’s River Bassas in any meaningful way. This would be Bassingbourn, Cambridgeshire. The suffix “bourn” denotes a stream, while “Bassing” is a combination of the personal name “Bassa” and “ingas,” denoting a tribe or clan. Thus, the name of this place is “the stream of Bassa’s people.” This is the closest known match to “the River Bassas” in Britain. The general geographical placement also makes this attractive, since it would have very much been in the heart of Anglo-Saxon territory, contributing to the attested reverse migration.

Another Confident Placement: Guinnion Fort

This does not mean that all of the battles ascribed to Arthur in the Historia Brittonum took place in or near the Midlands. One example of a battle site which is outside this area but quite confidently identified is Guinnion Fort. Again, while numerous theories have been proposed regarding this, most scholars agree on one particular location. That location is Binchester Roman Fort in the county of Durham. To the Romans, this was known as Vinovium.

The place name “Vinovium” would naturally evolve into “Guinouion,” which is very close to the Historia Brittonum’s “Guinnion.” Since it was not uncommon for the letter “u” to be corrupted into an “n” (and vice versa), some scholars have suggested that “Guinouion” became “Guinonion.” From there, the middle “o” was dropped as a result of a general simplifying of the place name. This would produce “Guinnion,” exactly as it is spelt in the Historia Brittonum. Therefore, while “Vinovium” is not a perfect match for “Guinnion,” many scholars believe that it is the most likely origin.

While Durham is quite some distance from the other battle sites that we have considered so far, it is still a logical location. It is not far from York, which was another very prominent Anglo-Saxon center in the 6th century.

Where King Arthur Fought His Battles

In conclusion, we can speculate about several of Arthur’s battle locations listed in the Historia Brittonum, though all are controversial to one degree or another. However, by starting with the most easily identifiable location, we can start to build a reasonable scenario. The location in question is Linnuis, identifiable as the region surrounding Lincoln. This makes strategic sense as the area in which Arthur fought battles against the Anglo-Saxons in the first half of the 6th century. It also accommodates the evidence for a reverse migration, which suggests that Arthur did not fight these battles on the fringes of Anglo-Saxon territory.

The first battle, at the River Glein, can likely be placed at the River Glen in Lincolnshire. The River Bassas, notoriously difficult to identify, is most probably identifiable as Bassingbourn in Cambridge for linguistic reasons as well as the greater strategic picture. Further away from the heartland but still at a prominent Anglo-Saxon site, Guinnion is most likely the Roman fort of Vinovium. Thus, it appears that the Historia Brittonum’s account of Arthur presents him as fighting the Anglo-Saxons deep inside their own territory, explaining why his campaigns were so damaging to them.