Conflict between Native Americans and European settlers over the centuries is no secret. However, the focus of study and remembrance on these conflicts often targets the nineteenth century, when resettlement and war were commonplace. Often overlooked but essential to the country’s development are the earlier, bloody struggles that make up King Philip’s War in what is now New England.

Background: The Mayflower, Plymouth, & Peace

When English colonists, known as pilgrims, arrived in New England in 1620, they were setting foot on land that the Wampanoag people had occupied for over 12,000 years. The Wampanoag are a confederation of Native American tribes that worked together throughout history in a military and governmental fashion while still maintaining sovereignty. Before the landing of the Mayflower, they had had various interactions with temporary European settlers, explorers, and fishermen. Some of these visits were peaceful, while other cases had resulted in skirmishes and Wampanoag people, such as a young man named Tisquantum, better known today as Squanto, being taken into slavery and transported to Europe. A great deal of the Native population was killed by European diseases to which they had no immunity, including a great epidemic between 1616-1619 known as the “Great Dying.”

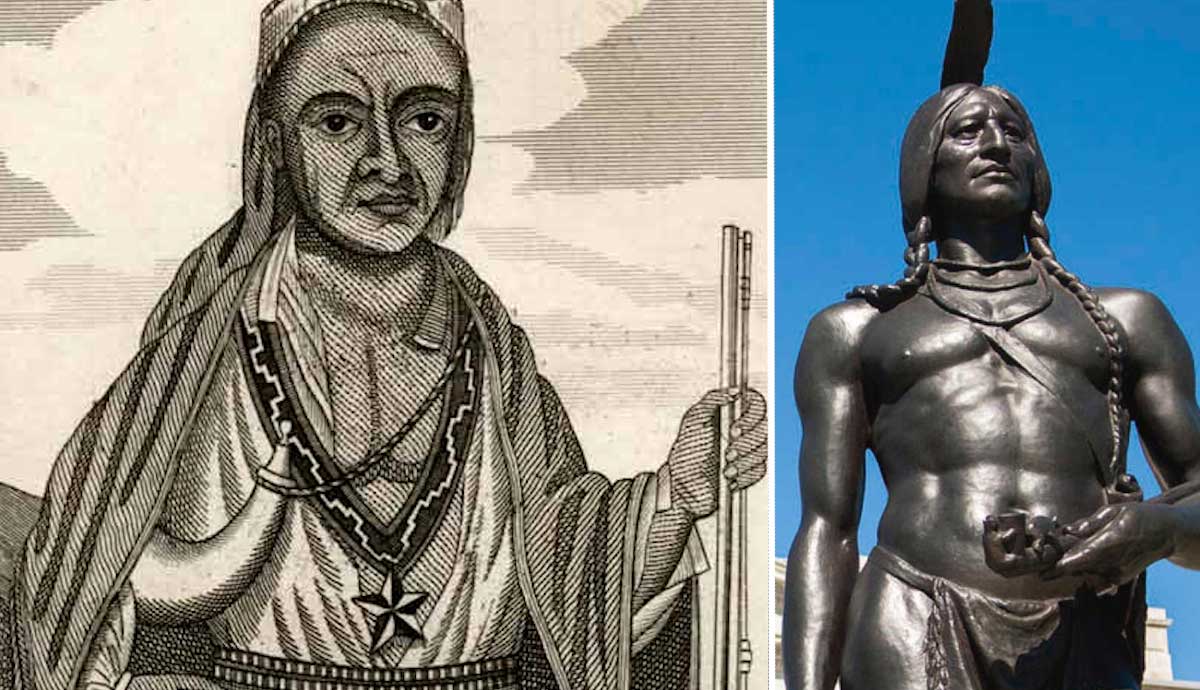

When the Mayflower arrived, the English people aboard were strangers in a strange land. They had limited resources and knowledge and thus were at a disadvantage. Rather than take advantage of this situation, the Wampanoag sachem, or inter-tribal leader, Ousamequin, also known as Massasoit, offered an entente to the group. Massasoit, of the Pokanoket tribe, not only wanted to prevent unnecessary conflict with the new visitors but wanted allies against the Wampanoag’s long-held enemies, the Narragansetts. Peace between the Wampanoags and the pilgrims held for approximately fifty years, though it was constantly tested. Tensions constantly were rising from the Englishmen’s land expansions beyond their original dwelling of Plymouth and their exploitation of local resources.

Who Was King Philip?

Massasoit had two sons: Wamsutta, known to the English as Alexander, and Metacomet, or Metacom, given the English name Philip. Upon Massasoit’s death in 1661, Wamsutta took his place as sachem. Unfortunately, Wamsutta’s reign would be short-lived. During a parley with the English in which he was questioned about a plot against the colonists, Wamsutta fell ill. Not long after returning home, he died. Metacom, now sachem, believed his brother had been poisoned by the English.

Metacom quickly stepped up to the plate as sachem and continued ongoing negotiations for land use and peace with the English. However, he was faced with many challenges. In addition to land exploitation and expansion by the English, Metacom watched some of his people and those of other local tribes become “praying Indians”: convert to Christianity, adopt English culture, and settle in missionary villages. On occasion, these “praying Indians” would serve as go-betweens, providing the English with information about what was going on in the Native villages. One of these individuals was a man from the Massachuset tribe named John Sassamon, who had been Harvard educated and converted to Puritanism. He helped establish one of the “Praying towns” at Natick and often served as an interpreter between Metacom and the English. He would come to play an even greater role as Metacom’s frustrations with the English increased and infringement onto Native land continued.

The Death of Sassamon & The Birth of a War

In January 1675, Metacom had come to the realization that there was no change on the horizon if the situation were to remain status quo. The English intended to continue expanding with no end in sight. He began to meet with other chiefs in the confederacy to determine what their approach would be. Some believed that John Sassamon reported the details of these meetings to the English governor, Edward Winslow. On one of his trips home from Plymouth, Sassamon died at a place called Assawompset Pond. The circumstances of his death are unclear, but suspicions have included murder, accidental drowning, suicide, and natural causes. However, the colonists in Plymouth came to the quick conclusion that Sassamon had been murdered. Three of Metacom’s supporters were arrested and quickly convicted, despite existing regulations requiring that each entity would try their own people for crimes. These three men were sentenced to death, and they were hanged. This action was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and by mid-year, King Philip’s War would be in full swing.

A Year of Bloodshed

Several skirmishes would mark the beginning of the war, including an attack on Governor Josiah Winslow’s home in early June. Not long after, the governor began raising a militia, the largest that had ever been seen in North America at the time. The government in Boston attempted to negotiate with Metacom’s confederation to no avail. By this time, the New England confederation included not only the Wampanoag tribes but others, including the Nipmuc nation and their historical enemies, the Narragansett. Despite past differences, the tribes could agree on one thing: they could not stand by and watch their lives forever changed by English encroachment.

On June 24, 1675, Metacom’s forces attacked the town of Swansea in what is now Massachusetts, an attack considered by many to be the official start of the war. The combined force of the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colony militias would come to the defense of Swansea. Over the next few months, a series of raids by the confederacy would be undertaken in parts of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Maine. The militia would retaliate, defending and counter-attacking. Soon, the colonial militia numbered over a thousand, and some Native nations, including the Mohegan, decided to ally with the English colonists. Some of the Narragansetts would end up leaving the confederation and joining the English side after a devastating attack on December 19th, in which their fort was burned by the militia, resulting not only in the deaths of warriors but of women, children, and the elderly, some of whom were burned alive or died of exposure after the attack. This would later become known as the Great Swamp Fight.

Some extraordinary devastation occurred during the conflict, including the destruction of many villages, both Native and white. For example, all white settlements on the western side of the bay in Rhode Island were razed in early 1676. Towns, including Deerfield, Squakeag, and Brookfield, were entirely abandoned. Another notable battle was Bloody Brook, where the majority of a colonial squadron was wiped out.

Captivity and internment was a hallmark of King Philip’s War. The Native confederation took numerous prisoners over the course of the war, often ransoming them. The English forced about 500 “praying Indians” of the Nipmuc tribe to move to Deer Island, off the coast of Boston Harbor. They were placed in an internment camp there, where many died from illness or were kidnapped by slavers from the Caribbean.

An End at Mount Hope

As 1676 progressed, Massachusetts Bay Colony hoped to encourage the opposing side to end their combative measures. The government offered amnesty to any Native Americans willing to surrender. Some took advantage of this opportunity but were still sold into slavery or executed anyways. In July, the English kidnapped and imprisoned Metacom’s wife and child. Metacom retreated to his home village, Mount Hope, with his remaining followers. He was pursued over the following weeks, and in August, Captain Benjamin Church led the group that would finally take down Metacom.

Church led a militia group from Rhode Island and is considered the first US Army Ranger. Church had previously formed friendships with Native Americans near his home, particularly the leader of the Sakonnet tribe, a woman sachem named Awashonks. However, Church would find himself fighting his former friend temporarily as she joined Metacom’s forces, though she would later side with the English near the end of the conflict. Regardless, his familiarity with Native tactics and culture would aid him in tracking and fighting Metacom’s forces. On August 12, 1676, Church’s group cornered Metacom on Mount Hope, and John Alderman, a “praying Indian,” fired the fatal shot that killed Metacom, ending not only the sachem’s life but King Philip’s War. After Metacom’s death, he was beheaded, his body drawn and quartered. His head was displayed on a pike outside of the town of Plymouth for over two decades.

Statistics: America’s Most Devastating Conflict?

When population rates are considered, King Philip’s War can be counted as the bloodiest conflict in American history. Over 2,500 English settlers were killed, which equates to about 30% of the population (See Further Reading, Cray, 2009). It is estimated that about twice as many Native combatants and civilians were killed. These people not only died as a result of battles but from the starvation and disease that accompanied the war era. Over half of the English settlements in the region were damaged or completely destroyed. English reach into the wilds of New England would expand in the years that followed, with the Wampanoag and other tribal populations dwindling and assimilating. After the war, around one thousand Native people were sold into slavery, most to the Caribbean.

King Philip’s War is often lost to history, but it provides context for the conflicts that would persist between colonists and Native Americans as the centuries continued. Several recurring themes would present for the first time during this fray and continue to ravage both Native and settling people of America: land theft, exploitation, internment, and enslavement. Metacom was unsuccessful, but his spirit and desire to preserve his culture deserve recognition.

Further Reading:

Cray, R.E. (2009). “Weltering in Their Own Blood”: Puritan Casualties of King Philip’s War. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 37(2). 106-123.