In his memoir My German Question: Growing Up in Nazi Berlin, historian Peter Gay recalls cycling through Berlin on the morning of November 10, 1938. The city, writes Gay, “seemed to have been visited by an army of vandals.”

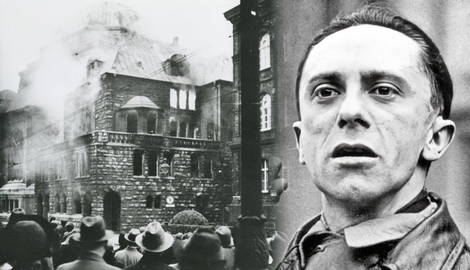

The broken glass and damaged merchandise scattered on the sidewalks were the result of an unprecedented wave of anti-Semitic violence instigated by the Nazi leadership. Between November 9 and 10, the Nazis vandalized Jewish-owned shops, businesses, and homes throughout the territory of the Third Reich. Known as Kristallnacht from the broken glass covering the sidewalks, the pogrom was a turning point in the regime’s anti-Semitic policy, foreshadowing the systematic persecution of European Jews.

Nazi Anti-Semitism & Kristallnacht

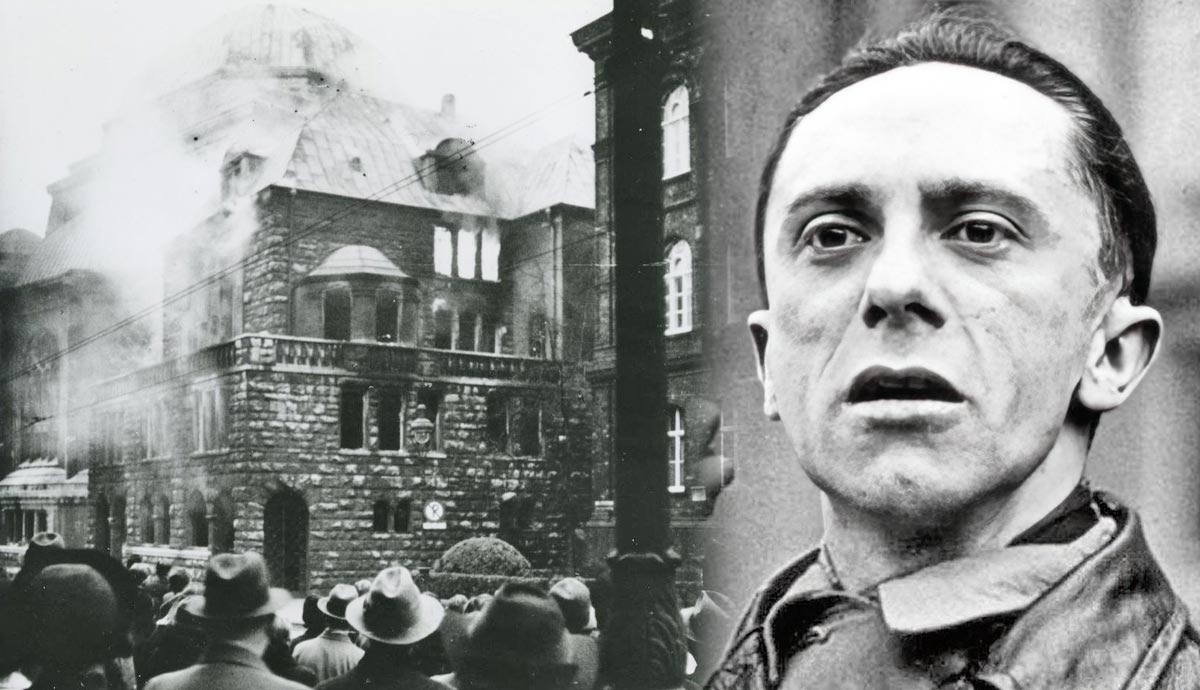

“The Jew,” wrote Joseph Goebbels in Der Angriff (the Nazi Party paper) in 1928, “is the enemy and the destroyer of unity created by blood, the deliberate destroyer of our race.” In postwar Germany, plagued by inflation and social instability, the Nazi Party, or NSDAP, identified the Jewish minority as the leading cause of the Weimar Republic’s problems. Indeed, anti-Semitism was a key component of the Nazis’ ideology and worldview. Influenced by Social Darwinism, a pseudo-scientific doctrine postulating the idea of racial struggle, Adolf Hitler saw the Jews as members of a subhuman race bent on weakening and corrupting the superior “Aryans.” The only way of restoring and preserving Germany’s racial purity was the eradication of the Jewish population from the country.

At the beginning of the 1930s, as the Nazis influence started growing considerably, the party’s Sturmabteilung (Assault Division) regularly harassed Jews and encouraged Germans to boycott Jewish-owned shops and establishments. Kauf nicht bei Juden (“Do not buy from Jews”), read a slogan usually printed on flyers handed out by SA members to passers-by. In 1933, when Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, the Nazi government began to pursue a repressive policy against the Jewish minority.

In April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service forbade Jews from becoming civil servants. At the end of the same month, the Law Against Overcrowding in Schools and Universities set a strict limit on the number of Jewish students educational institutes could enroll.

The process of segregation escalated in September 1935, when the Nazi Party, gathered in Nuremberg, announced the introduction of two measures, collectively known as Nuremberg Laws, depriving Jews of their citizenships and fundamental rights.

“A citizen of the Reich is only that subject, who is of German or kindred blood,” stated the Reichsbürgergesetz (Reich Citizenship Law). To prevent any “racial mixing,” the Blutschutzgesetz (Blood Protection Law) made marriages and sexual relations between Jews and “Aryans” illegal.

In November 1935, a supplementary decree of the Nuremberg Laws identified as a Jew anyone who had “one or two grandparents who were racially full Jews.” The same decree emphasized the Nazis’ plan to exclude all inhabitants of Jewish descent from German society: “A Jew cannot be a citizen of the Reich. He has no right to vote in political affairs, he cannot occupy a public office.”

Before the Kristallnacht: The Polenaktion

From 1933 to 1938, the Third Reich introduced around four hundred anti-Semitic laws and decrees. At the same time, the Nazi regime began to expel members of the Eastern European Jewish community from the country. Since the 19th century, numerous Jews had been coming to Germany from their Eastern homelands, where they struggled against poverty and widespread anti-Semitism. In 1938, around 50,000 Polish Jews resided in Germany.

In March 1938, when the Third Reich annexed Austria, Poland feared that the so-called Anschluss would lead many Jews with Polish citizenship to have to return to their home country. To avoid mass migration, the Polish government revoked the passports of all Jews who had lived abroad for more than five years. Toward the end of October, as Poland refused to lift the restrictions, the Nazi government used the disagreement as a pretext to launch a nationwide campaign of expulsion of Polish Jews from the territories of the Third Reich.

From October 27, around 25,000 Jews were forced to leave their homes. However, when they reached the German-Polish border, the Polish authorities refused to let them into the country. As a result, the displaced Jews were stranded for weeks, living in precarious conditions in the woods or refugee camps.

Among the victims of the so-called Polenaktion (Polish Action) was the family of Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew living in Paris. In October 1938, forced to leave behind most of their possessions and money, the Grynszpans were transported to Zbąszyń, a small Polish town. Unable to cross the border, they moved to the nearby refugee camp. Once Herschel received news of his family’s expulsion from Germany, he decided to draw attention to the plight of the Polish Jews with a desperate gesture. “I have to protest in a way that the whole world hears my protest, and this I intend to do. I beg your forgiveness,” he wrote to his uncle in Paris.

On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan went to the German Embassy in the French capital. Once inside, he shot the German secretary Ernst vom Rath multiple times. Arrested by the French police, Herschel was extradited to Germany in 1940.

November 9, 1938: A Death and a Commemoration

Ernst vom Rath died from his wounds on November 9, the anniversary of the failed Beer Hall Putsch. The news of his death reached Germany when the Nazi party leadership was holding a commemoration of the 1923 coup in Munich. On November 7, German radios had already reported the shooting at the German Embassy in Paris. As the story spread through the Reich, spontaneous anti-Jewish riots broke out in some cities and towns.

While Adolf Hitler sought to eradicate the Jews from Germany, in a 1919 letter, he had expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of pogroms as anti-Jewish weapons. For the future leader of the NSDAP, these acts of violence initiated from below were the embodiment of an “anti-Semitism of pure emotion.” These bursts of fury against single Jewish communities, however, would have a limited effect on the fight against the influence of Judentum (Judaism). The successful solution to the “Jewish problem” could be achieved only through the implementation of an “anti-Semitism of reason.” Only “a systematic and legal struggle” against the Jews could achieve their “total removal” from Germany, observed Hitler.

Despite his misgivings about pogroms, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party leaders saw the death of Ernst vom Rath as the perfect opportunity to merge the two types of anti-Semitism by coordinating a nationwide wave of violence against Jews. In the middle of the celebration for the Beer Hall Putsch, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, after conferring with the Führer, held an inflammatory speech denouncing the “cowardly murder” of the Embassy’s secretary.

The high-ranking officials gathered in the ballroom of the Old Town Hall understood Goebbels’ violent rhetoric as an instruction to initiate a series of pogroms in the territories of the Third Reich. At the end of the speech, Johann Heinrich Böhmcker, leader of the SA and mayor of Bremen, phoned his chief of staff, ordering that the local Stormtroopers should “destroy all Jewish businesses immediately” and set fire to all synagogues. The other leaders similarly rushed to send telegrams to or contact Nazi headquarters, branch offices, and stations. As the orders spread throughout the Reich, SS men, Brownshirts, and members of the Hitler Youth began to vandalize, destroy, and loot Jewish-owned shops, homes, and places of worship.

The Kristallnacht

On the night of November 9, the SS and SA systematically raided every Jewish group in the Reich. The attack was especially brutal in large cities such as Berlin and Frankfurt, homes of two of the largest Jewish communities. However, the violence and destruction reached even the most remote German villages.

The scope of the November pogroms was unprecedented in the history of Germany. “The entire German people is in rebellion,” wrote Joseph Goebbels in his diary. “The dear Jews will think carefully before they bump off German diplomats,” he commented.

The Minister of Propaganda’s private remarks reflected the official narrative of Kristallnacht promoted by the regime, claiming that the wave of violence was the result of a widespread Volkszorn (public resentment) provoked by the murder of Ernst vom Rath.

The thorough nature of the anti-Semitic terror, however, seemed to belie the image of the November pogrom as a spontaneous event. “On the order of the Gruppenführer immediately all the Jewish synagogues … are to be blown up or set on fire,” stated a report written by the SA office in Darmstadt. “The action,” added the author of the document, “is to be carried out in civilian clothes.”

The SA was one of the main perpetrators of the coordinated attack against Jewish properties and lives. A key player in the rise of the Nazi party, the Assault Division had been relegated to a secondary role after the purge of its leadership on the Night of the Long Knives (1934). For many SA leaders, the state-sanctioned pogrom was the perfect opportunity to reclaim their importance in the anti-Semitic persecution. In some cases, civilians joined the Storm troopers in their rampage. Others opted to remain silent observers. Some Germans, however, disapproved of the violence and helped their Jewish neighbors.

Throughout the German Reich, more than one thousand synagogues burned. The firefighters received explicit instruction not to extinguish the fires. Their only task was to prevent the flames from damaging the “Aryan” buildings nearby. Almost eight thousand Jewish shops and businesses were destroyed, their windows smashed by the SA. “During a walk towards Bahnhof Zoo-Kurfürstendamm on the morning of 10th November I convinced myself that in no Jewish shop was there even one window pane or glass display case still intact,” recalled Dr. Curt Meyer.

During the attacks, the SA and SS also broke into Jewish homes, rounding up around 300,000 men. “In the morning I went with some 80 prisoners to the police station (Prater, Ausstellungsstrasse), where some 1,000 poor victims had already been herded together in abandoned stables so that their bodies formed one solid mass,” reported a victim of the pogrom in Vienna. After being beaten and forced to perform acts of public humiliation, the prisoners were sent to the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen. They were released toward the end of 1938 upon agreeing to leave the country permanently.

The International Response to Kristallnacht

As news of the Nazi pogrom made its way outside Germany, the anti-Semitic violence evoked shock among the international community. “At 3-A.M. November 10, 1938 was unleashed a barrage of Nazi ferocity as had had no equal hitherto in Germany or very likely anywhere else in the world since savagery, if ever,” wrote David H. Buffum, the US consul in Leipzig. The diplomat also rejected the claim that the riots erupted from a “spontaneous indignation.”

The American Consul General Samuel Honacker was similarly appalled by the event: “the Jews of Southwest Germany have suffered vicissitudes during the last three days which would seem unreal to one living in an enlightened country during the twentieth century if one had not actually been a witness of their dreadful experiences.”

In the United States, countless newspapers published shocking accounts of the mass attack against German Jews. “Nazi Mobs Riot in Wild Orgy,” denounced the Los Angeles Times on November 11, 1938. “Eye Witness Tells Scenes of Terror in Berlin Riots,” reported the Oakland Tribune. Religious leaders also condemned the Nazi violent persecution: “Archbishop of Canterbury Protests Attack on Jews,” announced the Christian Science Monitor.

On November 15, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt criticized the pogrom during a press conference. “I myself could scarcely believe that such things could occur in a twentieth-century civilization,” he remarked. On the same occasion, Roosevelt also declared that he had recalled the American ambassador from the German capital. The public outcry against Kristallnacht, however, did not result in an increase in the annual immigration quota to allow German Jews to seek refuge in the United States.

“I would not like to be a Jew in Germany”: The Aftermath of Kristallnacht

On November 12, Hermann Göring gathered members of the government, the Nazi party, and the economic circle at the Reich Aviation Ministry. The agenda of the meeting was to assess the results of the Kristallnacht and formulate a plan that would exclude the Jews from the social and economic life of the Reich. As leader of the Four-Year-Plan, Göring had supervised the Aryanization of Jewish businesses and enterprises.

Now, the pogrom represented an opportunity to speed up the process of expropriation of all Jewish property. To this end, the participants in the November 12 gathering resolved to have the Jewish community pay for the devastation of the anti-Semitic riots. Additionally, they imposed a 1 billion Reichsmark “atonement tax” on the Jews. To make matters worse, the Nazis also forbade the victims of the pogrom from receiving compensation for the damages. “It’s insane to clean out and burn a Jewish warehouse then have a German insurance company make good the loss,” declared Göring in his opening remarks.

The goal of the radicalization of anti-Semitic legislation was to force the members of the Jewish minority to emigrate from the territories of the Third Reich. “I’d like to say again that I would not like to be a Jew in Germany,” commented Göring at the end of the November 12 meeting. Indeed, in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, about 120,000 Jews opted to leave Germany to escape from the progressively harsh anti-Semitic measures. In this sense, the November pogrom was a turning point in the Nazi regime’s Jewish policy, inaugurating a more violent attitude toward the Jews.

On November 24, the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps published an article with the title “Juden, was nun?” (“Jews, what now?”). The author hoped that the result of the exclusion of Jews from the Reich would be the “definitive end of Judaism in Germany, its total extermination.”