In the 16th century, a single man’s desire for wealth and fame would result in one of the deadliest conquests in modern human history. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico in February 1519, seeing victory in battle against the natives almost immediately. Only a few weeks into his venture, he met—or rather was gifted—the woman who would arguably be the key to his success: La Malinche, the interpreter who forged the path for the Spanish destruction of the Aztec Empire.

From Nobility to Slavery

La Malinche’s background is shrouded in mystery. Some sources indicate that her first name was Malinalli, meaning “grass” in Nahuatl, named after her day of birth on the Aztec calendar—which was believed to predict a child’s destiny. For children born on Malinalli, this meant nothing good. A life of misfortune and rebellion was ahead of her.

However, this is only one possibility for her name—one that was likely added to her story much later. A more convincing explanation, offered by historian Camilla Townsend, is that “Malinche” is actually derived from the name she would take as a Christian convert, Marina. According to Townsend, “Marina” was pronounced in the Aztec language Nahuatl as “Malina,” and the traditional “tzin” honorific was added to the end, resulting in Malintzin or Malintze. The Spanish pronunciation of this would have been Malinche.

One thing is more certain: she was likely born into the upper class. La Malinche’s fluency in multiple indigenous languages included that of the local upper class. More importantly, she could speak the courtly dialect of the region, which likely required a formal education to learn.

So how did this noble woman fall from grace?

The most well-known explanation comes from Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier under Cortés who wrote an account of the conquest. According to Díaz, La Malinche was the daughter of local Aztec rulers. His version of the story claims that her own mother sold her into slavery after the death of her father, securing the noble inheritance for her younger brother.

Aside from a lack of evidence, there are two primary reasons to call Díaz’s account into question. The first is that demonizing her parents further justifies La Malinche’s service to Cortés, while the second is that painting her as an outcast from her own community explains the role Catholicism would ultimately have in her life. Both are very convenient to the Spanish narrative.

The only certainty is that, somehow, La Malinche ended up a slave in Mayan territory.

Cortés’s Greatest Gift

Following Spanish victory at Tabasco, La Malinche and 19 other women were given to Cortés as spoils of war. The women were all promptly converted to Catholicism, a common practice in colonial Mexico. Converts were given brand-new names to match their brand-new religion, and so she received the first name scholars are sure of, Marina.

It is no surprise that Cortés quickly saw La Malinche’s potential. Her knowledge of indigenous languages was an invaluable skill, in addition to her experience navigating multiple Mesoamerican cultures, as a Nahua woman living among the Maya. But her role in Cortés’s life would soon evolve far beyond just translation. La Malinche became Cortés’s personal advisor, mistress, and mother to his first child. She even went into battle with him and is often depicted in artwork with a shield. Her permanent place at his side solidified her reputation as Cortés’s willing accomplice in the subjugation of what many viewed as “her own people.” But how much of the blame was hers to bear?

Translator, Mistress, Mother

To claim Cortés and La Malinche’s relationship was complicated would be an understatement. As a slave, Malinche did not actually belong to Cortés. Due to her noted beauty, Cortés gifted her to one of his top captains. What happened next is unclear. Some sources say Cortés simply took her for himself and gave his captain a different woman. Díaz’s account asserts that Cortés waited until his captain went off to Spain to begin living with his new mistress. However it happened, Cortés claimed La Malinche for himself.

All sources emphasize that La Malinche clearly stood out among the indigenous women. She was praised for her uniquely noble character, a proud woman “without embarrassment.” She held herself as would the daughter of a cacique (local ruler) rather than as a slave.

The relationship between Cortés and La Malinche varies in each telling of the story. Many accounts claim that La Malinche earned Cortés’s trust and love through her years of dedicated service to him. The loyalty appears to have been returned, with Díaz relaying that Cortés refused all women presented to him during their time together. Modern authors doubt the romantic aspect of their relationship, focusing instead on their successful partnership. The son they had together was the first mestizo born in the New World, earning La Malinche the title “Mother of the Mexican Nation.”

With the conquest complete, Cortés returned to his wife in Spain. He arranged for La Malinche to marry one of his soldiers and granted her extensive land as a wedding gift. She had one daughter with her husband, while her son with Cortés was executed at age 26 for taking part in a conspiracy. Their love story—if indeed it was love—may have been short-lived, but La Malinche never outgrew the association with Cortés.

Role in the Conquest

In Cortés’s letters to Spain detailing his conquest, he describes La Malinche simply as la lengua—“the tongue.” Cortés initially needed two interpreters, since La Malinche did not speak Spanish—but not for long. She quickly picked up the language living among the Spanish, making herself indispensable and the other translator unnecessary. La Malinche’s abilities ensured her success and, consequently, her survival.

Linguistic fluency was only the tip of the iceberg when it came to La Malinche’s value. The information she provided extended to cultural context, economic structure, and succession status of kingdoms. She even aided in converting the native populations by telling Christian stories in local tongues. In Cortés’s own words, “After God, we owe this conquest of New Spain to Doña Marina.”

Loyalty to the Spanish

Through whatever lens La Malinche’s participation in the conquest is viewed, her commitment to the Spanish was undeniable. In October 1519, the town of Cholula welcomed and took in the Europeans. Expecting allyship, a Cholula woman approached La Malinche and warned her of an attack they were planning by night. The woman promised La Malinche she could marry her son, a nobleman, if she were to join them. Yet Malinche told Cortés immediately.

The Spanish responded with what became known as the Cholula Massacre, killing 6,000 people in the span of two hours, one of many instances in which Doña Marina can be credited with saving Cortés’s life.

Meeting Montezuma

In November 1519, Cortés reached Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztecs, now known as Mexico City. Montezuma, the Aztec emperor they had heard of for months prior, was waiting for them when they arrived. Tenochtitlan under Montezuma was the center of an incredibly advanced civilization that held control over the surrounding city-states.

The famous first meeting of Montezuma and Cortés is always depicted with La Malinche in the center, translating between the two men. Though his motives remain unclear, Montezuma decided to allow the Spanish into his city. Only six days later, he was imprisoned in his own home. The chaos that followed led to Montezuma’s death and the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521. With the help of local indigenous groups, the Spanish took the city. The Aztec empire would never recover.

La Malinche’s Many Legacies

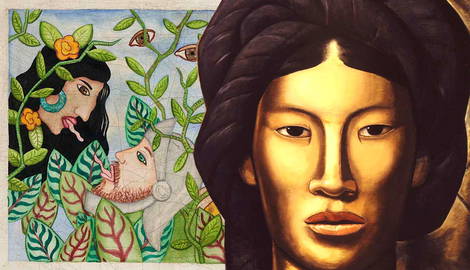

In the centuries since the Spanish conquest, La Malinche has been called everything from hero to sell-out to feminist icon. The term “Malinchista” in Mexico has come to mean “traitor.” Her name is now a serious insult condemning those who turn their backs on their own culture. Even the home she lived in outside of Mexico City is deemed “tainted” by association. La Malinche is at once considered the “mother of the Mexican race” and the perpetrator of the country’s “original sin.” She is the “Mexican Eve,” responsible for the first great mistake of the Mexican nation. Just as some condemn her as a traitor, still others view her as a tragic victim who was violated by the Spaniards. She represents all the women who were captured by the Spanish along with the land they claimed.

Considering Malinche through a feminist lens paints a very different picture. Her intelligence and natural leadership allowed her to break gender norms by assuming a place of influence at Cortés’s side. She broke free from slavery and survived on her own wit and strength. In this way, she is seen as a symbol of Chicana feminism. Her mind was so valuable that the success of an entire nation depended on it—making her dangerous in the eyes of many. She has even been considered influential in the development of machismo culture. Her story serves as a warning to men, emphasizing the fear of feminine betrayal and promoting forceful masculinity as a means of controlling cunning women.

Another view proposes the unappreciated role that Malinche’s translations may have had in aiding the indigenous populations. By acting as the mouthpiece of Cortés, La Malinche could choose exactly how the Spaniards’ words were delivered. She had the power to manipulate the message without either side knowing. Many defend her as an advocate for the natives. Knowing they could never win, she often convinced indigenous groups not to take up arms against the Spanish. The only evidence of this, however, are arguments documented between Malinche and another interpreter who claimed her translations to sometimes be inaccurate.

An Impossible Judgment

There is no way of knowing what was lost—or possibly gained—in translation with La Malinche. Because her own thoughts were never recorded, the world will never understand what her intentions were, how much choice she had, and what role her words played. At the very least, they ensured her survival.

Some may blame her for the success of the Spanish conquest; others still may argue that she prevented more bloodshed than she caused. After all, Cortés would have stopped at nothing to achieve what he desired.

One thing is certain: La Malinche succeeded as an interpreter, helping both sides understand each other a little bit better.